Follow-up of Children with Williams-Beuren Syndrome in Bulgaria

Received Date: April 06, 2024 Accepted Date: May 06, 2024 Published Date: May 09, 2024

doi: 10.17303/croa.2024.9.102

Citation: Elitza Betcheva-Krajcir (2024) Follow-up of Children with Williams-Beuren Syndrome in Bulgaria. Case Reports: Open Access 9: 1-22

Abstract

The Williams-Beurensmicrodeletion syndrome isa distinctive genetic congenital complex ofsymptoms, affecting the physi- cal, motor and speech development, aswell as most of the organs of the body. Sometimes difficult to be differentiatedfrom other rare genetic disorders in early childhood, it can remain unrecognized for manyyears. Ultimately, anexperienced pedi- atrician can recognize the characteristic symptoms and suspect the condition or can just suspectar are disorder and refer the patient to abroad ergenetic screening.After molecular genetictest for confirmation of the disease,the most optimal form of surveillance should be determined.This includesa coordinated multidisciplinary approach in a specialized center and in accordance with the current professional guidelines and recommendations for children with WBS. Early intervention strategies for supporting motor and speech development,as wellastraining for daily routines maintaining and integration are very beneficial for the patients. Regrettably, there are no such specialized pediatric centers for any patients with complex genetic disorders and intellectual disability in Bulgaria. Guidelines, recommendations and standards for surveillance and management of patients with rare diseases have scarcely been issued and professional information in Bulgarian language is barely accessible. Asaresult,even ifparents of the affected children are aware of the condition and the best healthcare strate- giesfor their child, enormous personal efforts are needed for planning each medical examination, finding each pediatric spe- cialist, and cover all expenses for specific intervention.

Keywords: Williams-Beuren Syndrome; Medical Genetic Counselling; Rare Genetic Disorders; Children's Healthcare in Bulgaria

Introduction

The Williams-Beurens microdeletion syndrome is a distinctive genetic congenital complex of symptoms, affecting the physical, motor and speech development, as well as most of the organs of the body. Sometimes difficult to be differentiated from other rare genetic disorders in early childhood, it can remain unrecognized for many years. Ultimately, an experienced pediatrician can recognize the characteristic symptoms and suspect the condition or can just suspect a rare disorder and refer the patient to a broader genetic screening. After molecular genetic test for confirmation of the disease, the most optimal form of surveillance should be determined. This includes a coordinated multidisciplinary approach in a specialized center and in accordance with the current professional guidelines and recommendations for children with WBS. Early intervention strategies for supporting motor and speech development, as well as training for daily routines maintaining and integration are very beneficial for the patients. Regrettably, there are no such specialized pediatric centers for any patients with complex genetic disorders and intellectual disability in Bulgaria. Guidelines, recommendations and standards for surveillance and management of patients with rare diseases have scarcely been issued and professional information in Bulgarian language is barely accessible. As a result, even if parents of the Affected children are aware of the condition and the best healthcare strategies for their child, enormous personal efforts are needed for planning each medical examination, finding each pediatric specialist, and cover all expenses for specific intervention.

The prevalence of WBS is similar in populations with diverse descent and is approximately 1 in 7 500 births. There is no specific population data for Bulgaria, however, similar numbers must be expected. Despite the similar health problems of WBA patients worldwide, WBS patients as well as other patients with rare genetic diseases in our country, are facing challenges, such as lack of specialized di- agnostic, of multidisciplinary teams, of national standards and guidelines for follow-up of patients with special needs. Thus, patients and their families must search for a "small-s- cale solution" for each specific medical problem from differ- ent healthcare providers and professionals, each being fo- cused on a limited number of symptoms but not on the pa- tients as a whole. Most diagnostics, surveillance and inter- vention expenses must be covered by patients and their fam- ilies. Furthermore, the healthcare system is completely un- prepared for the entering adulthood WBS-patients.

Generally, WBS is clinically recognized during childhood by neonatologists or pediatricians. The most com- mon suggestive findings are heart murmur, supravalvular aortic stenosis, delayed motor and speech development and/or the specific facial phenotype, historically known as the "Elfin facies". Confirmation of the suspected clinical di- agnosis is made by either targeted molecular genetic testing, or by common microdeletion syndrome genetic screening. Unfortunately, in Bulgaria most of the patients have barely any counselling afterwards, regarding the nature of the con- dition or the recommended follow-up procedures. None of the families that sought genetic counselling in our practice was referred to genetic counsellor; they all made an appoint- ment after their own research in the Internet. This manuscript addresses the challenges that five Bulgarian fam- ilies with a WBS-affected child had to face in order to under- stand the condition and summarizes the current recommen- dations for surveillance and management of WBS children that the families received from the genetic counselor.

Clinical Cases

Personal History

Within one-and-a-half calendar years 5 families with a WBS-affected child appointed genetic counselling in our practice, without being referred to it by any healthcare professional. Among the five children, aged from 7 months to 5 years-and-7-months, two are girls and three are boys.

No pathological findings were found during three of five pregnancies. A placental detachment at fifth lunar month (1. m.) was followed-up in one pregnancy. Intrau- terine fetal growth retardation was observed during one pregnancy (s. table I). Childbirth occurred between 35" and 41“ gestational week (g. w.) via vaginal delivery in one case; via planned cesarean section due to maternal indications in one case; via emergency cesarean section due to deteriora- tion of cardiac function in the rest three of the cases.

Growth indicators at birth were at the lower half of the nomogram plots: the weight-to-age ratio was between the 1“ percentile' (-2.9ñ z-scorez) and the 15" percentile (-1.04 z-score); the length-to-age ratio was between the 1“ (-2.30 z-score) and the 45° percentile (-0.12 z-score); the head circumference-to-age ratio - between the 16° (-0.98 z- score) and the 37" percentile (-0.32 z-score) (according to the standard nomograms of CDC 2000 and/or WHO [9]) (table 1).

One family was referred to genetic testing for WBS after the pediatric cardiologist suggested the diagnosis based on the facial phenotype and supravalvular aortal stenosis, identified shordy after birth. The first clinical pre- sentation of the syndrome in two children was pulmonary stenosis with “congenital heart murmur“; however, at this point WBS was not suspected. These two children, as well as two others, showed signs of motor and/or speech develop- ment delay, first noticed by their parents. All parents instinc- tively assigned their children to early intervention programs with physiotherapist, speech therapists and/or pediatric neu- rologist/psychiatrists, without knowing the cause of the de- lay. In three of these cases the healthcare providers recom- mended genetic testing for clarifying suspected general ge- netic disorder. One family was referred to genetic testing by a pediatric gastroenterologist, who examined the child re- garding feeding problems.

Molecular genetic testing expenses were covered by private funding in four of all five families; the analyses for one child were met by the hospital, to which the family was referred to for diagnostics. Upon receiving test results, none of the families was referred to genetic counselor and none of them received any professional information or rec- ommendations, concerning the WBS. All parents continued their intervention programs on own expenses: five families worked with physiotherapist; two families worked also with speech therapists and three families - with pediatric psychologist or psychiatrist. One family found information on the Internet about our genetic consultation and made an ap- pointment. The rest of the families followed, after being in- formed from the first family.

Further Clinical Findings

Mild supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) with a peak gradient of 25 mm was identified in one child within the first days after birth. Two children were found to have mild pulmonary stenosis shortly after their delivery. A he- modynamically insignificant foramen ovale was described in one child. Before genetic counselling only one child was regularly followed-up by a cardiologist regarding the SVAS. None of them has ever had blood pressure measurement (table 1).

Before genetic counselling only one child has had regular serum calcium level monitoring. Following genetic counselling, after calcium level testing was recommended, one child was found to have hypercalcemia, as total calcium was found to be 2.72 mmol/L (reference values 2.19-2.51) and ionized calcium (Caz’) in serum was 1.42 mmol/L (ref. values 1.16-1.32). Normocalcemia was acquired by dietary correction. Three of five children were found to have hy- povitaminosis D (Table 1), in contrast with the prevailing scientific data association of WBS with elevated vitamin D levels.

None of the five children had thyroid gland func- tion monitoring prior genetic counseling. Referred to clini- cal laboratory from our geneticist, one of five children was found to have hypothyroidism, with TSH levels of 9.23 mlU/L (ref. values 0.67-4.16) and fT4 levels of 10.24 pmo1/L (ref. values 11.5-22.7) and required hormone replacement therapy. One child showed subclinical hypothyroidism with slighdy elevated TSH level, but fT3/ ff4 within normal range and is under regular observation by endocrinologist.

Common finding in our patients were various her- niations that required surgical intervention. One child had left inguinal, right inguinal and umbilical hernia; one child had inguinal and umbilical hernia; one child had inguinal hernia only.

No hearing impairment was identified in any of the five children; however, no targeted evaluation besides the neonatal screening was ever done. Two families report- ed problems with excessive cerumen in their children.

No visual impairment or any other ophthalmologi- cal problems were known in any of the children. All of them have visible medial epicanthi. Two children have light-col- ored irides, which enables observation of the characteristic WBS stellate pattern.

All children demonstrate joint hypermobility, but none of them has spinal or other skeletal deformities and pathological contractures. All children have very elastic skin.

Breastfeeding/feeding difficulties in infancy and early childhood are reported in all families. Two of five chil- dren found transition to solid foods a real challenge.

Falling asleep and sleep duration problems are re- ported in three of the children. These problems were re- solved by regular bedtime routines introduced by parents af- ter recommendations by psychiatrists.

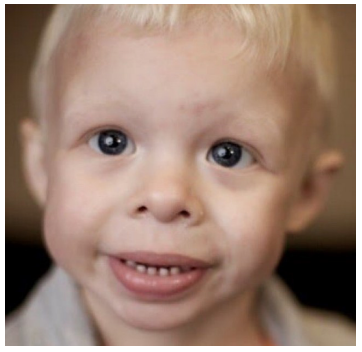

Psychological evaluation in all five children found moderate intellectual disability (generally corresponding to an IQ between 35 and 49). Motor development delay was present in all children, driving all families to start working with physical therapists. All children showed remarkable re- sults due to this intervention, however, as expected in WBS fine motor skills remain continuously impaired. Speech de- velopment is delayed as well, with typically more simplified speech compared to peers in all verbal WBS children but al- so with significant patient-to-patient differences, to a great extend dependent on speech therapy interventions. All chil- dren are very friendly and smiling a lot; they are highly ener- getic and hyperactive; they respond verbally or emotionally when being spoken to, and adore music, which has a stress reducing effect on them.

Two families feared stigmatization by surrounding people, including teachers and healthcare professional; they feel psychological and emotional pressure when they haveto talk about the condition of their child, especially outside the family.

Family History

Negative family history for congenital conditions, intellectual disabilities, reproductive failure or consanguini ty was found in four out of five families. Three first trimester pregnancy losses (of the proband's grandmother) and a child with an intellectual disability (a child of thegrandmother's sister) were reported for the maternal side inone family, but no diagnostic testing was done. Two children are firstborn in their families, and three have older siblings. Both partners were tested for the WBSmicrodeletion in one family, with negative result.

Discussion

Williams-Beuren Syndrome (WBS)

Clinical Characteristics

The Williams-Beuren syndrome (WBS) is a congenital genetic disorder with prevalence 1:7,500 - 1:20#000 worldwide, across all populations. It is a multisystem diSease with variable clinical manifestation [10-12]‘

General Features

WBS individuals have very distinct facial phenotype observed from birth on and described historically as an ”Elfin facies". Typical features are broad forehead, bitempora1 skull narrowing and a dolichocephalic head configuration. The zygomatic bone is underdeveloped and flat, making the cheeks appear small and rounded. Periorbital swelling and thin eyebrows are common. Adults with WBS typically have characteristic long face and neck.

The eye color is often light, with irises having a characteristic stellar-like (lace-like) pattern (visible in lightirises). Over half of the patients (>65%) have strabismus (most often esotropic) and about half of them may develop hyperopia. Cataract development is common with advancing age; a specific vascular pattern with more convoluted vessels may be present in the fundusi amblyopia and impaired depth perception might cause balance problems on uneven surfaces or stairs. Younger children often have epicanthus; obstructed nasolacrimal duct is observed more commonly.

The nose back is short, broad and flat, the tip is rounded and the nostrils are often anteverted. The philtrum is high and flat, the vermilion is thicker, full and prominent; the mouth-opening is relatively wide. There is a pro- nounced micrognathia. Teeth are affected by malocclusion and diastema; microdontia and enamel hypoplasia are common.

The earlobes are larger, which becomes more prominent with age. Children more often develop middle ear inflammation and about 60% develop chronic otitis me- dia. Excessive cerumen secretion is typical. Most patients (84-100%) develop hyperacusis with discomfort at sounds of at least 20 db lower than unaffected individuals; some pa- tients have phonophobia, with slow tolerance development with aging. Paradoxically, individuals with Williams syn- drome have an extraordinary affinity for music, they love to listen to music and dance; music often helps stress-reducing and attentionfocusing for longer time. About 63% of chil- dren and about 92% of adults develop progressive, usually mild to moderate sensorineural deafness, affecting especial- ly the high frequencies range in adults. Vision and hearing problems require annual life-long ophthalmological and otorhinolaryngological follow-up [1,2,5,7,8,11,14,15].

Growth and Development

Growth delay and low weight are very common features of WBS, sometimes starting even during pregnancy with noticeable intrauterine growth retardation. To some ex- tend growth problems result from feeding difficulties in in- fancy, motor delay incl. the fine motoric delay affecting the tongue muscles, the muscle hypotonia, joint hypermobility, etc. Children with WBS usually have weight, height and head circumference below the 75th percentile of the average range for their age. A major growth spurt occurs at the time of puberty, but altogether, WBS adults tend to be short in stature. For this reason, adapted growth charts for individu- als with WBS were issued, for growth evaluation during childhood by pediatricians at each visit [1,2, 7-9,16].

Intellectual disability (DSM-5) is usually mild (IQ 50-69) to moderate (IQ 36-49) in 75% of cases. Concep- tual skills (literacy, goal orientation, concept of numbers, money and time, etc.) are slightly to significantly more limit- ed than in peers. Difficulty in acquiring academic knowledge is observed and a personalized approach in education is necessary. Social relationships are immature, social inter- pretation and understanding of hints is difficult, and com- munication is more direct; emotional controlling is difficult and tantrums are not uncommon. Adult WBS individuals are able to learn taking care of themselves and performing daily activities with adequate and intensive intervention [10,11].

Specific cognitive profile (which does not neces- sarily correlate with the IQ level) is observed in 90% of the cases and is characterized by impaired visual-spatial intelli- gence and abilities to manipulate numerical information, but well-developed short-term memory, as well as remark- able speech skills and an exceptional ability for remember- ing and recognizing faces in adulthood. Speech and lan- guage skills start developing later compared to other peers, but adults have unexpectedly good enunciation, auditory memory, and vocabulary, and often impress with their speech. Arithmetic skills are greatly affected throughout life. Basic motor skills develop slower, and fine motor skills re- main impaired throughout life. The capacity for behavioral adaptive responses is severely affected at all ages. Attention deficit and hyperactivity are frequently observed [10,11,15,17,18].

Individuals with WBS are extremely friendly, full of empathy, love to be among other people and are usually preferred company; they are very emotional, easily fright- ened and often have specific anxiety [10,11] . Sleep problems (prolonged latency, reduced sleep efficiency) are common, perhaps caused by night-time melatonin absence or reduced peak [11,19,20].

Cardiovascular System

Cardiovascular disorders (in about 80% of the cas- es) are clinically the most significant group of symptoms, eti- ologically associated with the insufficient elastin synthesis. Reduced elastin amounts in the wall of the large arteries, re- sults in stenosis. A supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) is found in about 75% of patients. It may be of segmental “hourglass” type or may involve a greater span of the aortic wall, and sometimes requires surgical correction [1-3,7,8,21]. WBS patients require special considerations pri- or to any sedation and/or anesthesia (e.g. during surgery). Individuals with biventricular outflow tract obstruction or otherwise at increased risk of myocardial insufficiency must be consulted by experienced cardiologist and anesthesiolo- gist [22-25].

Peripheral pulmonary stenosis in childhood is of- ten auscultated as a heart murmur; if more severe stenosis may cause fatigue and shortness of breath even without physical exertion. In the majority of the cases, it improves naturally with aging [1,2,7,8].

Arterial hypertension as a result of stenosis of re- nal arteries can be systemic, but it can also be asymmetric and restricted to a certain part of the body, as a result of nar- rowing of local arteries; thus, measured blood pressure val- ues can vary over different blood vessels. For this reason, blood pressure of WBS patients should always be measured in at least three extremities. Arterial hypertension requires good control (by standard medications), especially in child- hood when it is usually not expected and identified [1,2,7,8]. Other elastin-dependent arteriopathies (e.g. mesen- teric) may cause local symptoms, such as abdominal pain.

The cardiovascular complications of elastin arterio- pathy in WBS must be expected and followed-up regularly (Doppler echocardiography, ECG): every 3 months during the first year of life, at least once annually until 5 years of age and once every 2-3 years lifelong. Blood pressure values in 3 or all 4 extremities must be recorded at each pediatri- cian/physician visit or at least once a year throughout life. In adulthood surveillance includes searching for signs of: mitral valve prolaps, aortic valve insufficiency, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, hypertension, prolonged QT-interval, arte- rial stenoses, by means of Doppler echocardiography, ECG, or CT, MRI, catheterization if necessary [1,2,7,8,26].

Endocrine System and Microelements

Usually, mild idiopathic hypercalcemia and hyper- calciuria develop in 15-45% of all WBS patients, requiring regular control. Serum calcium levels should be monitored every 4 months until 12 months of age, every 4-6 months from one to two years of age, and once in 2 years or as need- ed after this age and throughout life. Urine calcium levels and calcium/creatinine ratio testing (random spot or 24- hour urine) is recommended once a year. Clinical signs of hypercalcemia are irritability, vomiting, constipation, mus- cle cramps. The exact pathophysiological mechanism of the hypercalcemia in WBS is not fully understood, but to some extend it is related to the increased intestinal resorption of calcium and the susceptibility to hypervitaminosis D. First line management of hypercalcemia is controlled (but never fully restrictive) dietary intake (for example of dairies). Rare- ly, a drug therapy under cardiological monitoring might be necessary.

Excessive vitamin D levels are commonly found, however, hypovitaminosis D was prevalent among Bul- garian WBS patients. For this reason, plasma vitamin D lev- els should be monitored prior any correctional activities. By hypervitaminosis, avoiding common children food supple- ments with vitamin D and strong skin sun protection factor might be recommended [2,7,8].

WBS individuals are commonly born with hypo- plastic thyroid gland and might develop clinical (in 5-10% of the cases) or subclinical (in ca. 30% of the cases) hypothy- roidism. Clinical hypothyroidism causes further deteriora- tion of the already compromised physical growth and intel- lectual development. Therefore, a lifelong monitoring of serum TSH and fT4/fT3 levels is essential for all patients [1,2,7,8].

Premature puberty (at 6-12 years) occurs in about 18% of cases. Therapeutic intervention is rarely necessary, but consultation with an endocrinologist might be neces- sary. Individuals of both sexes are fertile [1,2,7,8].

Diabetes mellitus and obesity are common in WBS adults, requiring beginning with serum glucose screening at a young age (between 13 and 20 years). Dietary control and regular daily activity are necessary [1,2,7,8].

Musculoskeletal and Nervous System

Muscle hypotonia in infancy and joint hypermobil- ity cause compensatory posturing of the body, in order to maintain balance and are a co-factor in motor development delay. Adolescents and adults may develop peripheral mus- cle hypertonus and hyperreflexia [11]. Over time, an abnor- mal gait, spine deformities (kyphosis, scoliosis, lordosis), as well as joint contractures may develop [1,2,7,8].

Lifelong fine motor skill impairment causes object handling and writing difficult, and is also associated with solid food mouth processing, as tongue mobility is affected [1].

In rare cases, a Chiari type I anomaly (confirmed by brain magnetic resonance imaging) can be assessed, caus- ing cerebellar symptoms such as ataxia, dysmetria, tremor, dysdiadochokinesis, etc. [11]. A consultation with a neurolo- gist is also held once a year or at necessity [1,2,7,8].

Gastrointestinal System

Gastrointestinal disorders include breastfeeding and feeding difficulties in childhood. Constipation is very common and obstinate. Intermittent abdominal pain is very typical and might result from various processes, such as me- senteric artery stenosis; gastrointestinal reflux; hiatal hernia; peptic ulcer; cholelithiasis; diverticulitis; ischemic bowel dis- ease; bowel-motility problems; rectal prolapse; hemor- rhoids; intestinal perforation; it can also be psychogenic - out of fear [1,2,7,8].

Urinary System

About 50% of WBS patients develop renal artery stenosis, associated with arterial hypertension. About 10% have congenital genitourinary malformations. Bladder diver- ticula develop over time in about half of the cases, and nephrocalcinosis - in less than 5% [1,2,7,8]. Pollakiuria and enuresis are found in at least half of the children. Diurnal in- continence might last until the age of 4; nocturnal enuresis might continue by the age of 10 and ca. 3% of adults may still have it [1].

Connective Tissue

Common aberrant connective tissue findings are umbilical and inguinal herniations, susceptibility to divertic- ula of the bladder and the colon, and rectal prolapse. Joint hypermobility or contractures not rare. The voice is often shrill because of the insufficient elastin in the vocal cords, the skin is hyperextensible, lax and soft [1,2,7,8,11].

Recommendations for Surveillance and Follow-up of Children with WBS

Key efforts in surveillance of WBS patients are focused on follow-up, prevention, symptomatic treatment and interventions for supporting their speech, motor and in- tellectual developments. Useful ageadapted checklists of rec- ommended clinical examinations, their regularity and suggestive findings are issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Canadian Association for Williams Syn- drome [2,16]. Furthermore, the Canadian Association pro- vides adapted WBS growth charts for height, weight and head circumference in female and male patients [16]. A summary of these recommendations, adapted with minor changes from the American Academy of Pediatrics check- list, is presented in table 2. Recommendations include:

-Thorough physical examination and growth monitoring (height, weight, head circumference) at every physician visit until age of 5 and at least once annually life- long.

-Cardiovascular assessment (echocardiography, ECG) at least once every 3 months up to 1 year of age, once annually until 5 years of age and once every 2-3 years there- after (depending on the individual situation). Screening for hypertension and elastin-based arteriopathy of the aorta, the pulmonary arteries, the renal and some other large ar- teries in all ages, as well as for mitral prolapse, aortic valve insufficiency, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, prolonged QT- interval, and arterial stenoses. Blood pressure and heart fre- quency are registered at each physician visit over the first years and at least once annually lifelong. Blood pressure measurement should include minimum three, preferably all four extremities. Hypertension drug therapy follows stan- dard protocols after renal artery stenosis is excluded.

-Cardiac surgery - surgical correction of severe supravalvular aortic stenosis, pulmonary artery stenosis, re- nal artery stenosis, mitral valve insufficiency might be neces- sary at an early age.

Any surgical intervention or other procedure re- quiring sedation or anesthesia necessitates cautious cardio- logical and anesthesiologic evaluation prior to procedure, to avoid myocardial insufficiency due to ventricular artery ob- structions.

-Serum calcium levels evaluation every 4 months for the first year of life, every 4-6 months from 1 to 2 years of age and once every 2 years for life (or as necessary). Urine calcium levels evaluation (screening for hypercalciuri- a) and urine calcium/creatinine ratio (random spot or 24- hour) once a year. Vitamin D levels are commonly impaired and should also be regularly monitored.

-Screening for hypothyroidism trough TSH serum level monitoring (together with FT3 and FT4 or sub- sequently) should be done once annually up to 3 years of age and every 2 years thereafter lifelong.

-Ophthalmological evaluation for visual impair- ment or other problems (e.g. strabismus) should be done once annually; WBS adults are predis osed to early catar- acts. Obstruction of the lacrimal ducts is a common finding.

-Otorhinolaryngological evaluation with audio- gram for early identification of sensorineural hearing im- pairment is recommended once annually up to 30 years, and once in 5 years thereafter. Common findings are otitis media and excessive cerumen secretion. Some patients need antiphones to cope with their hyperacusis.

-A single ultrasound screening by nephrologist for kidney and bladder malformations, and renal artery stenosis is recommended. Further follow-up in children is at the discretion of the specialist and in adults Doppler US should be done once every 10 years. Annual basic urine screening and evaluation of urine calcium/creatinine ratio, as well as serum urea (BUN) and creatinine levels are help- ful for early detection of nephrocalcinosis and kidney func- tional impairment. Recurrent urinary infections are more common (in about 30% of cases).

-Constipation is a very common problem (associ- ated with muscle hypotonia, hypercalcemia, etc.) and must be addressed regularly and intensively by the parents. Gas- tro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is common and im- portant for the differential diagnosis of abdominal pain, which can be also resulting from, hiatal hernia, peptic ulcer, cholelithiasis, diverticulitis, ischemic bowel disease, mesen- teric arteries stenosis but also psychogenic (anxiety, panic at- tacks). Feeding problems are very common, especially the dislike of new or solid foods or foods with certain textures. They can be overcome very slowly, with great parental pa- tience and sometimes with support from a speech therapist.

-Annual evaluation for herniations.

-Annual orthopedic assessment for contractures, spine deformities (kyphosis, scoliosis, lordosis).

Neurological assessment is recommended in case of recurrent headaches, dysphagia, ataxia, feeling of dizzi- ness and weakness, to exclude Chiari I malformation (by MRI); annual basic neurological evaluation of muscle tonus might be discussed.

-WBS patients are predisposed to diabetes and obesity. Therefore, a balanced diet and exercises are essen- tial for their health. Screening for glucose intolerance and hyperglycemia by serum glucose levels and oral glucose tol- erance test (OGTT) starts annually before 20 years of age.

-Puberty might begin earlier, however rarely pre- cautious and usually no medical therapy is necessary; WBS individuals are fertile and have 50% chance of having an af- fected child.

-Regular dental evaluation and care are recom- mended, however most of the patients have fear of these ex- aminations especially in childhood; this may prompt treat- ment under sedation.

-Further family planning is important part of the genetic counselling and should elucidate all details about re- currency risks and options for preimplantation and prenatal testing in future pregnancy.

-Working with different specialists is very helpful for the WBS patients and their families. It requires patience and special approach. Studies demonstrate that early and regular intervention programs are very helpful in speech and motor development, with remarkable results into adult- hood. Training programs for schooling in daily living and independency to some extend are very beneficial. Working with psychologist and/or psychiatrist helps coping with ansi- ety, panic attacks, fears, sleep disturbances or hyperactivity. Due to the significant contrast between the level of develop- ment in different cognitive areas (e.g., very good verbal and nonverbal reasoning, but impaired spatial understanding), general tests (such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children) are not appropriate for assessing the intellectual impairment, and rather tests for independent assessment of the cognitive domains (such as the Differential Ability Scales II) are recommended [27].

Contact of families with other WBS-families and patient groups is very beneficial.

Inheritance

In most cases, Williams syndrome occurs de nova, i.e., the deletion is due to a random spontaneous (newly) oc- curring event in the formation of one of the gametes of one parent. In case the parents have a normal phenotype, corre- sponding to absence of a germline deletion, the probability of having a subsequent affected child is low, but the risk is slightly higher than the population risk, tending towards 1%. The reason may be one of the following: gonadal mosai- cism in the parent (there are a few rare familial cases of Wil- liams syndrome described, with more than one child with the syndrome in a family of clinically healthy parents) in which case the recurrence risk cannot be evaluated; pres- ence of asymptomatic carrier of an inversion polymorphism on chromosome 7 in one parent, occurring in 25% of par- ents of children with WBS, but in only 6% of individuals in the general population, with a recurrence risk estimated at 1:1750. Therefore, it is recommended, when planning a sub- sequent pregnancy, the proband's parents to consider prena- tal or preimplantation diagnosis. Siblings of individuals with WBS in parents with inversion may also anticipate such a diagnosis in family planning.

Individuals with WBS of both sexes are fertile and can transmit the deletion to their offsprings with a probabili- ty of 50% for each pregnancy, which requires either con- trolled contraception or prenatal diagnosis planning [1,4,27-32].

Molecular genetic features

WBS is a common microdeletion syndrome, caused by loss of 1.55 Mb (mega bases) in the long arm of chromosome 7 (at locus 7q11.23) in over 90% of the cases. In the remaining up to 10%. of cases it is 1.54 Mb in size. It results in haploinsufficiency of 26 to 28 genes, associated with the typical clinical manifestations of the condition - a contiguous genes syndrome. Rarely, the deletion may be larg- er, inevitably causing more severe clinical presentation. The WBS deletion always includes the elastin gene [l,l 1,25,29]. “Golden standard” in molecular genetic testing for WBS testing is fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with 7q1l.23-specific probes. Currently, other CNV-detection techniques, such as multiplex ligation-dependent probe am- plification (MLPA) and array-based technologies, are regu- larly used, especially by broader clinical differential diagno- sis [I].

Future Directions

With increasing clinical recognition of the WBS and publishing of more clinical and other information on the condition, interest on WBS research is growing. Efforts are made to clarify the exact role of each of the deleted 26 (28) genes in the syndrome pathogenesis and especially in the neurodevelopment; to understand the causes and the fea- tures of the specific cognition profile and anxiety disorders in WBS; to understand the pathogenesis of cardiovascular, neurological and other pathogenic findings in WBS-pa- tients (more information can be found for example at the Williams Syndrome Association internet page).

Conclusion

Even though there is no etiological treatment for WBS, efforts should be focused on follow-up, prevention, symptomatic treatment and early interventions, in order to support motor, speech and intellectual development [1-3,7,8,26,30]. As described, WBS patients require lifelong regular medical surveillance from health care professionals with various medical background. In childhood, being cared for by their parents and followed-up by pediatricians, which are relatively familiar with the condition, in most Eu- ropean countries the WBS patients usually receive adequate surveillance. However, after 18 years of age, WBS patients cannot be followed-up by their pediatricians anymore; gen- eral practitioners and physicians are usually unaware of WBS and some patients naturally lose their parents. Several problems can occur at this point, regarding: the transition into adulthood-healthcare system; the assignment of a so- cial worker who is responsible for the well-being of the pa- tient and of a health care coordinator; the lack of specialized healthcare institution for evaluation and follow-up of pa- tients with rare disorders; the necessity of a general practi- tioner that is aware of the conditions and its possible compli- cations [1,2,7,8,26]. The above-described clinical cases re- veal some weak sides of our social and healthcare system re- garding patients with rare and chronic conditions, for example

- Insufficient state policy regarding genetic test- ing and genetic counselling, illustrated by the negligeable le- gal basis - only a small section of the Bulgarian Health Act devotes to clinical genetic testing. By comparison, the Genet- ic Diagnosis Act in Germany (GenDG), adopted in 2010, regulates all aspects of human genetics in detail, describes the obligations of healthcare providers to the patients, and establishes an independent interdisciplinary commission for genetic diagnosis (GEKO), which has so far defined eleven guidelines for medical genetic diagnosis, in com- pliance with the current level of scientific and medical devel- opment. The need to update and adopt an adequate legisla- tive framework in our country emerges in our every-day-- work as medical geneticists.

- Negligible opportunities for the genetic profes- sionals: to be the driver of an initiative to change the legisla- tion; to be the initiator of the preparation and approval of national standards, guidelines and regulations for genetic testing and counseling; to be supported and acknowledged by official institutions as professional organization that is ap- pointed and responsible to raise the awareness among healthcare providers with different background about the benefits and indications for genetic counselling and testing.

- Negligible opportunities for covering of the ex- penses for genetic testing, counselling and intervention pro- grams by the only health insurance fund in the country. For most affected families this is the main reason for abstaining from referral to geneticist. This on the other hand results in lack of prevention and missed therapeutic opportunities.

- Lack of any specialized healthcare center with a multidisciplinary team, where patients with complex genet- ic and other rare disorders can receive a coordinated surveil- lance and management for a variety of medical problems.

- The lack of national genetic standards, state poli- cy and information, makes most healthcare professionals and affected families unaware of the benefits of genetic counselling and testing.

- There are almost no state-supported interven- tion programs for people with speech, motor or intellectual deficiency (most are private), nor any guidelines for estab- lishing the most optimal strategy for improving the health status of patients [2,7].

Our efforts as genetic counselors are to help pa- tients and their families understand the complex nature of genetic disorders, to support them in accepting the situa- tion and to prepare sufficient information about expected future development. During genetic counselling, we have the opportunity to spend long time with the patients and their families and to get familiar with their greatest fears. We are the professionals, responsible to provide current knowledge and recommendations r the follow-up, surveil- lance and management of patients with rare genetic condi- tions. Knowing what to expect enables the physician to make informed clinical decisions.

An Informed Consent

We acknowledge the children with William- s-Beuren syndrome and their devoted parents, brothers and sisters, for their support and trust! Anonymized publication of the data in this article was agreed to and authorized by the parents of children with Williams syndrome consulted in our practice.

The photographic material used is made available in the public domain with a delegated right to its use provid- ed that the cited source is named.

Glossary

Amblyopia - "lazy eye”; a neurological problem in which the brain does not correctly perceive and process the image received from one eye, and as a result it is excluded from the vision process.

Anteverted nostrils — the nostrils are oriented for- ward instead of mostly downward.

Vermilion — the red part of the lips; divided into upper and lower vermilion.

Esotropia - convergent strabismus, with the gaze of both eyes deviated towards the nose.

Epicanthus — the upper eyelid skin fold that covers the inner ocular corner.

Diastema — greater distance between teeth

Dolichocephalic configuration — longer anterior-- posterior size of the skull, relative to its width.

Malocclusion - an incorrect arrangement of teeth that are not lined up.

Micrognathia — smaller mandible bone.

Microdontia - smaller teeth.

Proband — the patient who is the focus of genetic counseling.

OGTT — oral glucose tolerance test

WBS — William-Beuren syndrome

Strabismus - squint.

Philtrum the relief groove between the nose and the upper lip.

Phonophobia — fear of certain sounds.

Hyperacusis - increased sound sensitivity with reduced noise tolerance.

Cerumen - earwax.

- CA Morris (1993) "Williams Syndrome," in GeneRe- views((R)), M. P. Adam et al. Eds. Seattle (WA).

- G. Committee on (2001) “American Academy of Pedi- atrics: Health care supervision for children with Williams syn- drome," Pediatrics, 107: 1192-204.

- BR Pober, CA Morris (2007) "Diagnosis and manage- ment of medical problems in adults with Williams-Beuren syndrome,“ Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 145C: 280-90.

- K. Farwig, AG Harmon, KM Fontana, CB Mervis, CA Morris (2010) "Genetic counseling of adults with Williams syndrome: a first study," Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 154C: 307-15.

- CA Morris (2010) ”Introduction: Williams syndrome," Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 154C: 203-8.

- CB Mervis, DJ Kistler, AE John, CA Morris (2012) ”Longitudinal assessment of intellectual abilities of children with Williams syndrome: multilevel modeling of perfor- mance on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-Second Edi- tion,” Am J Intellect Dev Disabil, 117: 134-55.

- C Forster-Gibson, JM Berg (2013) ”Health Watch Table — Williams Syndrome," H. W. T. W. Syndrome, Ed., ed. The Internet: Surrey Place Centre, 2013, p. Considera- tions and Recommendations for Williams syndrome patients.

- CA Morris, SR Braddock, G Council On (2020) ”Health Care Supervision for Children With Williams Syn- drome, Pediatrics, 145: 2.

- D. Gräfe (2023) "Ped(z) Kinderarzt Rechner." O 2008-2021 Daniel Gräfe. https://pedz.de/de/willko mmen.html (accessed Jan 2023, 2023).

- CB Mervis, AE John (2010) “Cognitive and behavio- ral characteristics of children with Williams syndrome: impli- cations for intervention approaches,“ Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 154C: 229-48.

- CA Morris (2010) “The behavioral phenotype ofWil- liams syndrome: A recognizable pattern of neurodevelopmen- t,” Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet, 154C: 427-31.

- P Kruszka et al. (2018) "Williams-Beuren syndrome in diverse populations,“ Am J Med Genet A, 176: 1128-36.

- GM Araújo (2019) Figura 1- Fisionomia de um porta- dor da Síndrome de Williams.

- M Winter, R Pankau, M Amm, A Gosch, A Wessel (1996) "The spectrum of ocular features in the William- s-Beuren syndrome," Clin Genet, 49: 28-31.

- J Atkinson, S Anker, O Braddick, L Nokes, A Mason, F Braddick (2001) “Visual and visuospatial development in young children with Williams syndrome,” Dev Med Child Neurol, 43: 330-7.

- T.C.A. f. W.S. (CAWS). The Canadian Association for Williams Syndrome (CAWS) homepage Online. Avail- able: https://www.williamssyndrome.ca/

- CB Mervis, BF Robinson, J Bertrand, CA Morris, BP Klein-Tasman, SC Armstrong "The Williams syndrome cogni- tive profile," Brain Cogn, 44: 604-28.

- J. Van Herwegen (2015) "Williams syndrome and its cognitive profile: the importance of eye movements,” Psychol Res Behav Manag, 8: 143-51.

- AB Blackmer, JA Feinstein (2016) “Management of Sleep Disorders in Children With Neurodevelopmental Disor- ders: A Review," Pharmacotherapy, 36: 84-98.

- D. Annaz, CM Hill, A Ashworth, S Holley, A Kar- miloff-Smith (2011) "Characterisation of sleep problems in children with Williams syndrome,“ Res Dev Disabil, 32: 164-9.

- RT Collins, P Kaplan, GW Somes, JJ Rome, (2010) "Long-term outcomes of patients with cardiovascular abnor- malities and williams syndrome,“ Am J Cardiol, 105: 874-8.

- TM Burch, FX McGowan, Jr, BD Kussman, AJ Pow- ell, JA DiNardo, (2008) "Congenital supravalvular aorticstenosis and sudden death associated with anesthesia: what's the mystery?,“ Anesth Analg, 107: 1848-54.

- M Olsen, CJ Fahy, DA Costi, AJ Kelly, LL Burgoyne, (2014) ”Anaesthesia-related haemodynamic complications in Williams syndrome patients: a review of one institution's ex- perience,“ Anaesth Intensive Care, 42: 619-24.

- AJ Matisoff, L Olivieri, JM Schwartz, N Deutsch (2015) “Risk assessment and anesthetic management of pa- tients with Williams syndrome: a comprehensive review,“ Pae- diatr Anaesth, 25: 1207-15.

- GJ Latham, FJ Ross, MJ Eisses, MJ Richards, JM Gei- duschek, DC Joffe (2016) “Perioperative morbidity in chil- dren with elastin arteriopathy," Paediatr Anaesth, 26: 926-35.

- CA Morris, CO Leonard, C Dilts, SA Demsey (1990) "Adults with Williams syndrome,” Am J Med Genet Suppl, 6: 102-7.

- CB Mervis, SL Velleman (2011) “Children with Willi- ams Syndrome: Language, Cognitive, and Behavioral Charac- teristics and their Implications for Intervention," Perspect Lang Learn Educ, 18: 98-107.

- LR Osborne et al. (2001) ”A 1.5 million-base pair in- version polymorphism in families with Williams-Beuren syn- drome,“ Nat Genet, 29: 321-5.

- M Bayes, LF Magano, N Rivera, R Flores, LA Perez Ju- rado (2003) "Mutational mechanisms of Williams-Beuren syn- drome deletions,” Am J Hum Genet, 73: 131-51.

- CA Morris, SA Demsey, CO Leonard, C Dilts, BL Blackburn (1988) “Natural history of Williams syndrome: physical characteristics,“ J Pediatr, 113: 318-26.

Tables at a glance

Figures at a glance