The New Approach For Free Gingival Graft Removal

Received Date: February 19, 2022 Accepted Date: March 19, 2022 Published Date: March 21, 2022

doi: 10.17303/jdoh.2021.9.103

Citation: Hugo Dalazoana (2022) The New Approach For Free Gingival Graft Removal. J Dent Oral Health 9: 1-10.

Abstract

Introduction: The importance of keratinized tissue (KT) around implants have been extensively discussed an the literature agree that a band of keratinized gingiva is essential to prevent implants from mucositis and perimplantites. This article aimed to describe a case report of a new surgical approach for free gingival graft (FGG) removal as an alternative technique to harvest epithelized connective tissue from palate to prevent excessive tissue removal from the donor site.

Case Presentation: A 48-year-old female was attended at Orbis Institute for rehabilitation of anterior implants. A free gingival graft (FGG) was indicated with a modification on the used angle of the double scalpel handle (Harris scalpel) to remove a free gingival graft (FGG) with minimal damage and scars to the palate. This article describes an alternative use for the double scapel handle to remove a total thickness flap composed of epithelium and connective tissue. The application of this technique is described in a clinical case that presented deficiency and soft tissue defect around implants.

Conclusion: this FGG modification technique can be considered a minimum invasive alternative to gain sufficient amount of keratinized gingival tissue around implants.

Key findings: the main clinical finding in this study was to evidence the importance of a homogeneous tissue removal in thickness with a unique and simple instrument.

Keywords: Gingival Phenotype; Free Gingival Grafts; Autogenous Grafts; Autografts; Dental Implants; Soft Palate; Soft Tissue Grafting

Background

The presence of a keratinized tissue (KT) band around the implants has been widely discussed in the literature. The long junctional epithelium, the parallel-oblique organization of the connective tissue fibers runs to the titanium surfaces and does not attach to the implant [1,2]. Studies have suggested that implants sites without an adequate width (≤ 2 mm) of KT may display increased susceptibility to inflammation and loss of peri-implant soft and hard tissues [1-3]. The KT act as a physical barrier between the oral environment and the underlying connective tissues of the periodontium [4,5] and areas with less than 2 mm of KT persisted to remain inflamed [1]. Gingival augmentation is mandatory to prevent periodontal disease and peri-implantitis independent of phenotype [5-7], specially on thin phenotype which was associated with a higher risk for recession/ and could compromise the soft tissue esthetics [7,8]. Harvesting good-quality epithelized connective tissue grafts are important and thickness of 2mm to allow blood supply, revascularization and integration of new tissue to the host site, demystifying the need for very thick grafts [1,9-11]. To avoid donor site morbidity, different approaches for harvesting an FGG from the palate, while aiming at minimizing patient morbidity and complications [12]. This case report presents a new approach technique for epithelialized graft removal from the palate using a double scapel handle with a 1,5mm distance between blades, in a conservative model, giving the patient more comfort for the post operatory period.

Clinical Presentation

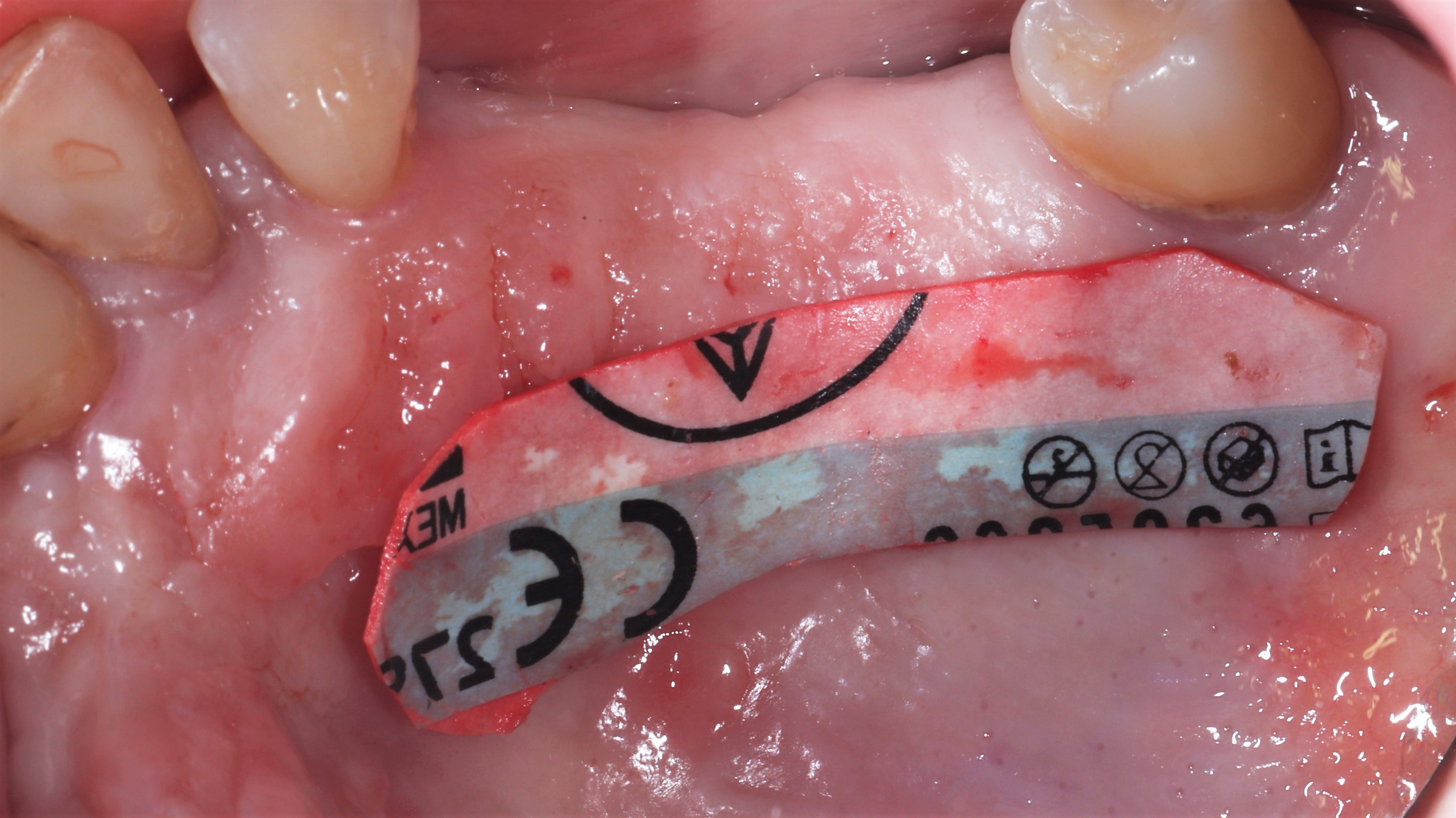

A 48-year-old female was attended at Orbis Institute complaining about pain and plaque accumulation on inferior anterior implants. Periodontal clinical examination, root planning procedures and needed for free gingival graft surgery was evaluated. Patient showed no systemic disease, not taking any medications, no known allergies, and nonsmoker. The site with less than 2mm of keratinized tissue were indicated for surgery (Figure 1). Verbal patient consent was obtained.

Case Management

The patient rinsed 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate solution for 2 minutes and local anesthetic (mepivacaine 2% with epinephrine 1:100.000, DFL, Brazil) was administered to the surgery site and donor area. A marginal horizontal linear incision was made at the mucogingival junction (microblade), creating a partial thickness flap, leaving an intact periosteum (Figure 2). The horizontal dimension of the recipient area was determined according to the mesiodistal extension of the area without keratinized tissue. The mucosal flap was detached leaving bone covered by periosteum (Figure 3). A template was made and transferred to the donor site. A double-blade scalpel is used to initiate the incision from the mesio-disto distance of the graft. A distance of 1,5mm between the blades allows the removal of a regular thick graft (Figure 4). The variation of the technique is in the parallel angulation of the double-blade scalpel cable tangenting the external epithelium of the palate. One of the blades runs all mesio-disto distance outside the graft, while the internal blade create the graft thickness (Figure 5). The second incision is made at the mesio and disto ending and the third incision on the internal base (Figure 6). The palate was sutured (6-0 nonresorbable monofilament) (Figure 7). Graft was adapted to the recipient site (Figures 8 and 9) and anchored to the periosteum by simple interrupted sutures (5-0 nonresorbable monofilament - Techsuture Brazil) (Figure 10). Suturing was continued along the lateral borders of the graft until complete stability of the graft was achieved. Patient was instructed to rinse twice daily (15 days) with 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate (Periogard, Colgate, Brazil) and toothbrushing was discontinued in the surgical area until sutures removal. Antibiotic (amoxicillin 500 mg, 3 times daily), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (Nimesulide 100 mg, 12/12 h) and analgesic (Dypirone 500 mg, 6/6 h) was prescribed for 07 days. Patient reported minimum discomfort post surgery. Sutures were removed at 7 days and 14 post surgery and monitored weekly until healing (Figures 11 and 12).

Clinical Outcomes

Using the double-blade scalpel, a standardized and reproducible gingival graft was obtained. The use of two blades mounted on a single scalpel handle provides the removal of a standard graft in all clinical cases.

Discussion

There is an extensive discussion about the quantity and quality of KT in order to maintain peridontal and peri-implant tissue healthy. Literature related to the need for a minimum 2mm keratinized gingiva band for periodontal and peri-implant health [13,14]. In case of abscence of KT around implants, a free gingival graft is welcome to prevent mucosites/perimplantites. Tthis work respect the idea that the keratinized tissue is fundamental for biological sealing around the implants, idealizing this forms a favorable long-term prognosis of supported implant prostheses. The literature has shown the effectiveness and the advantages of recovering the KT band around the implants and FGG is the most used graft technique for this purpose. The major issue for FGG is not the technique by itself, but related to the morbidity condition that affects the patient after surgery. The angle variation used in a double blade scalpel handle (Harris scapel) with a distance of 1,5mm between blades, allowed the removal of adequate band of keratinized tissue sufficient for free gingival graft. In 1,5mm of removed graft are the epithelial layers and lamina propria of connective tissue responsible for gold standard of grafts quality. The healing process of the graft to the recipient site is fastly processed due to the adequate revascularization of the all graft layers, where very thick grafts are lost due to a lack of adequate vascularization and the consequent death of the outermost layers of the graft. The healing depends primarily on the formation of anastomoses between existing vessels in the graft and circulation in the periosteal connective tissue bed via new sinusoidal vessels [15]. In summary, an instrument that facilitates the removal of an adequate band of keratinized tissue for grafting, clearly allows to apply all the concepts already determined in the literature regarding the thickness of the epithelized grafts as well as reducing the patient's postoperative morbidity.

Acknowledgments

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Conflicts of Interests

This paper was funded by the professionals own resources and report no conflicts of interest.

- Lin GH, Chan HL, Wang HL (2013) The significance of keratinized mucosa on implant health: a systematic review. J Periodontol 84: 1755-67.

- Sculean A, Chappuis V, Cosgarea R (2000) Coverage of mucosal recessions at dental implants. Periodontol 73: 134

- Monje A, Blasi G (2018) Significance of keratinized mucosa/gingiva on peri-implant and adjacent periodontal conditions in erratic maintenance compliers. J Periodontol 90: 445-53.

- Haggerty PC (1966) The use of a free gingival graft to create a healthy environment for full crown preparation. Case history.. Periodontics 4: 329-31.

- Perussolo J, Souza AB, Matarazzo F, Oliveira RP, Araujo MG (2018) Influence of the keratinized mucosa on the stability of peri-implant tissues and brushing discomfort: a 4-year follow-up study. Clin Oral Implants Res 29: 1177-85.

- Souza AB, Tormena M, Matarazzo F, Araujo MG (2016) The influence of peri-implant keratinized mucosa on brushing discomfort and peri-implant tissue health. Clinical Oral Implants Research 27: 650–55

- Kim DM, Neiva R (2015) Soft Tissue Non–Root Coverage Procedures: A Systematic Review From the AAP Regeneration Workshop. Periodontol 86: S56-S72.

- Giannobile WV, Jung RE, Schwarz F (2018) Groups of the 2nd osteology foundation consensus evidence-based knowledge on the aesthetics and maintenance of peri-implant soft tissues: osteology foundation consensus report part 1- Effects of soft tissue augmentation procedures on the maintenance of peri-implant soft tissue health. Clin Oral Implants Res 29: 7-10.

- Zigdon H, Machtei EE (2008) The dimensions of keratinized mucosa around implants affect clinical and immunological parameters. Clin Oral Implants Res 19: 387-92.

- Wei PC, Laurell L, Lingen MW, Geivelis M (2002) Acellular dermal matrix allografts to achieve increased attached gingiva. Part 2. A histological comparative study. J Periodontol 73: 257-65.

- Berglundh T, Lindhe J (1996) Dimension of the periimplant mucosa. Biological width revisited. J Clin Periodontol 23: 971–3.

- Zucchelli G, Mele M, Stefanini M (2010) Patient morbidity and root coverage outcome after subepithelial connective tissue and de-epithelialized grafts: a comparative randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 37: 728-8.

- Buser D, SennerbyL, DeBruyn H (2000) Modern implant dentistry based on osseointegration: 50 years of progress, current trends and open questions. Periodontol 73: 7-21.

- Avila-Ortiz, G, Gonzalez‐Martin O, Couso‐Queiruga E, Wang H (2020) The peri‐implant phenotype. Journal of Periodontology. doi:10.1002/jper.19-0566.

- Nobuto T, Imai H, Yamaoka A (1988) Micro-vascularization of the free gingival auto- graft. J Periodontol 59: 639-46.

Tables at a glance

Figures at a glance