Differences in Anti-Glycation Activity Depending on the Part of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam.)

Received Date: November 21, 2025 Accepted Date: December 01, 2025 Published Date: December 03, 2025

doi:10.17303/jfn.2025.11.204

Citation: Mari Suto, Hirofumi Masutomi, Hiroyuki Sasaki, Katsuyuki Ishihara (2025) Differences in Anti-Glycation Activity Depending on the Part of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam.). J Food Nutr 11: 1-16.

Abstract

Glycation nonenzymatic reactions between sugars and proteins produces advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which are implicated in atherosclerosis and diabetic complications. Safe, food-derived antiglycation agents are therefore needed. Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) is a nutritious crop in which the storage root is consumed, whereas the leaves, stems, and roots are often discarded. We compared the antiglycation activity of extracts from the leaves, stems, roots, and storage roots of sweet potato to explore value-added uses of these underutilized parts. Tissues were lyophilized and extracted with eight solvents of varying polarity (H₂O; ethanol 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100%; methanol; and chloroform/methanol at a ratio of 2:1). The antiglycation activity of the 32 extracts was assessed as inhibition of fluorescent AGE (F-AGE) formation in the HSA–glucose model. Among the parts, the activity ranked as follows: leaf > root > stem > storage root. HPLC analysis revealed the presence of polyphenols across all parts, with caffeoylquinic acids (CQAs) being the dominant compounds. Dicaffeoylquinic acids (diCQAs) were more active than mono-CQAs and caffeic acid. These findings indicate that sweet potato, especially its leaves and roots, is a promising source of food-grade antiglycation agents, providing a basis for the effective use of underutilized sweet potato tissues as functional ingredients.

Keywords: Sweet Potato, Anti-Glycation, Advanced Glycation End Products (Ages), Polyphenols, Caffeoylquinic Acids

Introduction

Reducing sugars react nonenzymatically with protein amino groups, leading to glycation. Early-stage Schiff bases form stable Amadori products, which later oxidize and condense into advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [1]. While some AGEs appear biologically inert, others impair cellular function and are implicated in aging, chronic inflammation, atherosclerosis, and diabetic complications [2]. Glycation control is key to food chemistry and disease research, with inhibition offering therapeutic potential. Aminoguanidine, initially for diabetic complications, is now limited by safety concerns [3]. The search for safe, effective antiglycation agents from food is a major research focus.

Plant-derived polyphenols show antiglycation activity, with their mechanisms and relevance increasingly understood. They are classified into flavonoids (e.g., catechin, quercetin) and nonflavonoids (e.g., resveratrol, chlorogenic acid), many of which act as antioxidants and prevent AGE formation [4]. In a BSA–glucose in vitro model, catechin markedly suppressed AGE-associated fluorescence [5], and coffee-derived chlorogenic acid scavenged methylglyoxal in the same system [6]. Plant-derived polyphenols inhibit AGE formation more effectively than aminoguanidine, highlighting their potential as safe antiglycation agents.

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.), a staple crop from the genus Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae), is valued for its dietary fiber and vitamins [7]. The main edible organ is the storage root; other parts, such as leaves, stems, and non-storage roots, are often discarded after harvest, underscoring a need for their effective utilization [8]. Studies of storage roots have identified diverse polyphenols, including caffeoylquinic acids (CQAs) [9, 10]. Most work has focused on antioxidant activity, and evidence for antiglycation activity is largely limited to purple sweet potato extracts [11, 12]. Because the extraction efficiency and bioactivity of plant antioxidants vary substantially with tissue and solvent [13, 14], detailed comparative studies in sweet potato remain scarce. Therefore, to better utilize underused sweet potato resources, we compared antiglycation activity of extracts from various plant parts and analyzed phenolic composition to identify part-specific characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human serum albumin (HSA; lyophilized powder, ≥96% by agarose gel electrophoresis) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Japan (Tokyo, Japan); aminoguanidine hydrochloride (AG) was obtained from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan); Folin–Ciocalteu phenol reagent was obtained from MP BioJapan (Tokyo, Japan); gallic acid (GA) was obtained from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan); caffeic acid (CA) was obtained from Kanto Chemical (Tokyo, Japan); 3-CQA (3-O-caffeoylquinic acid), 4-CQA (4-O-caffeoylquinic acid), and 5-CQA (5-O-caffeoylquinic acid) was obtained from Nagara Science (Gifu, Japan); and 3,4-diCQA (3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid), 3,5-diCQA (3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid), and 4,5-diCQA (4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid) were obtained from ChemFaces (Hubei, China). Unless otherwise noted, other reagents were special grade or HPLC-grade and were obtained from Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Industries or Kanto Chemical. Purity information for all reagents is provided as obtained from suppliers. Unless otherwise noted, compounds were ≥95% purity.

Samples

This study used sweet potatoes (cv. Beniharuka) harvested in 2020 in Ibaraki, Japan. After washing with tap water, tissues were dissected into leaves, stems, roots (non-storage roots), and storage roots. Samples were air-dried at room temperature and then lyophilized using an FDU-540 lyophilizer (EYELA, Tokyo, Japan). The dried material was ground into a powder using an MX-X501 grinder (Panasonic, Osaka, Japan) and stored at −80 °C until use.

For extraction, 0.5 g of dried powder was mixed with 25 mL of solvent and homogenized for 2 min using a T25 digital ULTRA-TURRAX (IKA, Osaka, Japan). The solvents used in this study were H₂O: 20, 40, 60, or 80% (v/v) ethanol; 100% ethanol (EtOH); 100% methanol (MeOH); or chloroform/methanol (2:1, v/v; CM). After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered. The extraction was repeated three times, and the supernatants were combined, filtered, and concentrated to dryness (NVC-1100, EYELA, Tokyo, Japan). All extractions using aqueous ethanol or methanol were performed at room temperature (22–25 °C). Following evaporation to dryness, the extracts were reconstituted in the corresponding solvent and stored at −80 °C, protected from light, until analysis. To maintain stability, all extracts were analyzed within 6 months of preparation.

For the lipid-soluble fraction, 0.5 g of dried powder was extracted with 100 mL of CM (2:1, v/v) under reflux for 2 h; the procedure was repeated twice. The dried residues were reconstituted to 10 mg/mL.

Across four plant parts (leaves, stems, roots, and storage roots) and eight solvents (H₂O, 20% EtOH, 40% EtOH, 60% EtOH, 80% EtOH, 100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM), a total of 32 extracts were prepared. Extraction yields are listed in Supplementary Table 1. For the antiglycation assay, extracts were dissolved in DMSO; for other assays, extracts were dissolved in the corresponding extraction solvent and diluted as appropriate before testing.

Measurement of Anti-Glycation Effect (HSA-Glucose Glycation Reaction Model)

An HSA–glucose glycation model was employed as described previously [15]. Sample solutions were added at 10% (v/v) of the reaction volume to a mixture containing 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 8 mg/mL HSA, and 200 mM glucose, and incubated at 60 °C for 40 h. Distilled water served as the negative control. After incubation, the fluorescence of fluorescent AGEs (F-AGEs) was measured (excitation 370 nm/emission 440 nm), and the percent inhibition of F-AGE formation was calculated relative to the control. Antiglycation activity was expressed as aminoguanidine (AG) equivalents using an AG calibration curve.

To ensure valid comparison of antiglycation activity across extracts prepared using different solvents, all extracts were evaluated at a standardized set of initial concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 10.0 mg/mL). Only data points that fell within the linear range of the AG calibration curve were used for AG-equivalent calculations. This approach ensured that solvent-dependent variations in antiglycation activity were assessed under consistent dose conditions. Each extract was examined at up to three concentrations selected from this set, depending on turbidity or precipitation observed at higher concentrations. To prevent optical interference, concentrations were adjusted as needed, and AG-equivalent values (μmol AG-eq/g dry weight) were calculated only from data points within the linear range of the calibration curve. When multiple concentrations satisfied this criterion, their mean value was reported. Phenolic standards were measured at 10, 50, and 100 μM. AG equivalents (μmol AG-eq/μmol compound) were calculated by comparing inhibition values within the linear range; when more than one concentration qualified, the mean was used.

Measurement of Total Polyphenols by Folin–Ciocalteu Method

The Folin–Ciocalteu method was performed according to ISO 14502-1:2005 [16]. Briefly, 100 μL of sample solution was mixed with 2.0 mL of distilled water and 500 μL of 5-fold-diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, followed by 500 μL of 10% (w/v) aqueous sodium carbonate. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, absorbance was read at 760 nm. Total polyphenols were quantified as gallic acid equivalents (mg GA-eq/g dry weight) using a GA calibration curve.

Each extract was measured at up to three dilutions within 0.1–10 mg/mL. To ensure accuracy, values were calculated only from data points within the linear range of the GA calibration curve; when multiple dilutions qualified, their mean is reported.

Quantitative Determination of Phenolic Compounds by HPLC

Phenolic compounds were quantified by HPLC (1260 series, Agilent Technologies, Hachioji, Japan) following Sasaki et al. [17]. The column was a Cadenza CD-18 (4.6 mm i.d. × 250 mm, 3 μm; Imtakt, Kyoto, Japan). The column temperature was 40 °C. Mobile phases were 0.4% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B); separation was achieved with a linear gradient from A:B = 93:7 to 60:40 over 0–33 min. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, the injection volume was 10 μL, and detection was at 325 nm. Standards were CA, 3-CQA, 4-CQA, 5-CQA, 3,4-diCQA, 3,5-diCQA, and 4,5-diCQA. CQA species lacking authentic standards were quantified as chlorogenic acid (5-CQA) equivalents.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Antiglycation activity, total polyphenols, and phenolic compound levels were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. Interaction terms were included, and interaction effects were observed in all analyses. Associations were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation. Two-way ANOVA and correlation analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 8.4.3 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA). Multiple regression was performed in EZR (Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan), a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) based on a modified version of R Commander that adds commonly used biostatistical functions. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

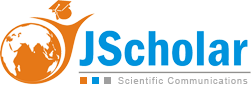

The antiglycation activity of the 32 extracts was assessed as inhibition of fluorescent AGE (F-AGE) formation in the HSA–glucose model. Results are summarized in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2. Across plant parts and solvents, leaf extracts showed higher activity in 40%, 60%, and 80% EtOH, in 100% MeOH, and in CM. Root extracts were also higher in 40–80% EtOH and 100% MeOH. In stems and storage roots, solvent-dependent differences were minimal. When parts were compared within a given solvent, the rank order was leaf > root > stem = storage root in 40–80% EtOH and 100% MeOH. In 100% EtOH, leaves exceeded stems and storage roots. In CM, leaves and roots exceeded stems and storage roots.

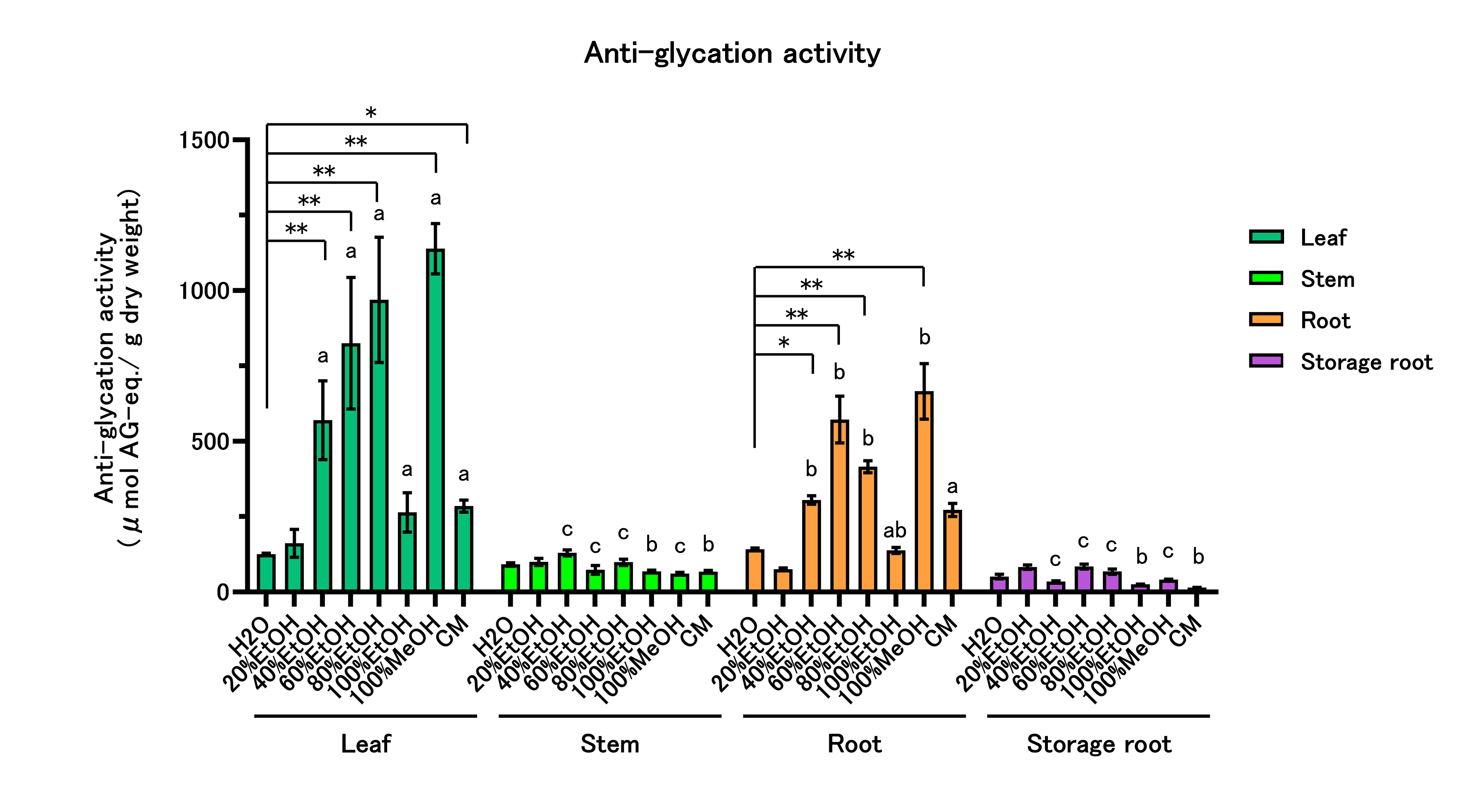

Total polyphenol content (TPC) was determined for all extracts (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, TPC was highest in 60–100% EtOH and in 100% MeOH. In stems, TPC was lowest in 100% EtOH and 100% MeOH. In roots, TPC peaked in 60–80% EtOH and 100% MeOH but was lowest in 40% and 100% EtOH. In storage roots, TPC was lowest in 100% EtOH. Across-part comparisons within each solvent: TPC ranked leaf > root > stem > storage root in H₂O, 20–80% EtOH, and CM. In 100% EtOH, the order was leaf > stem = root > storage root; in 100% MeOH, leaf > root > stem = storage root.

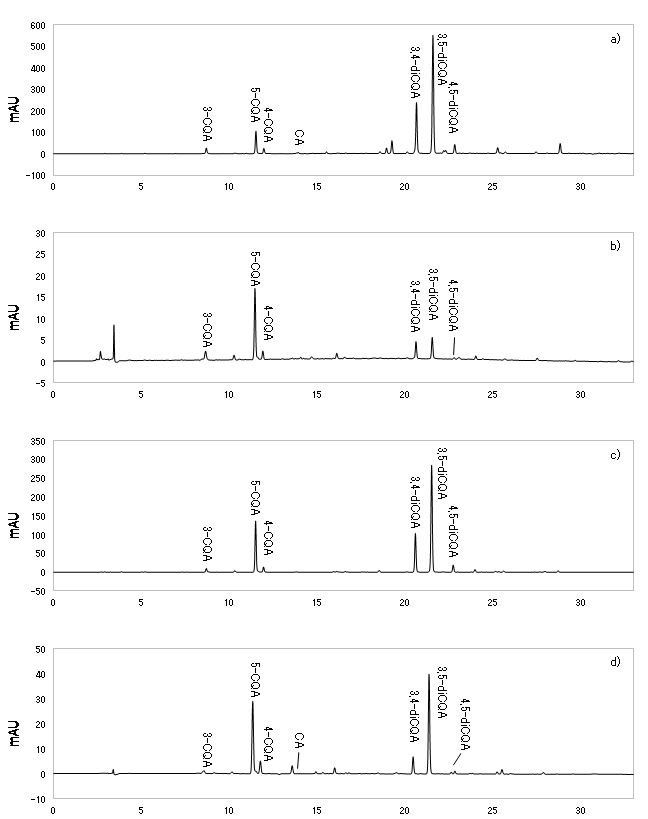

Because the Folin–Ciocalteu assay responds mainly to phenolic hydroxyl groups, these findings suggest that in sweet potato, phenolics contribute to antiglycation activity. We therefore profiled major phenolic constituents by HPLC. Seven compounds were detected across all parts: CA, 3-CQA, 4-CQA, 5-CQA, 3,4-diCQA, 3,5-diCQA, and 4,5-diCQA.

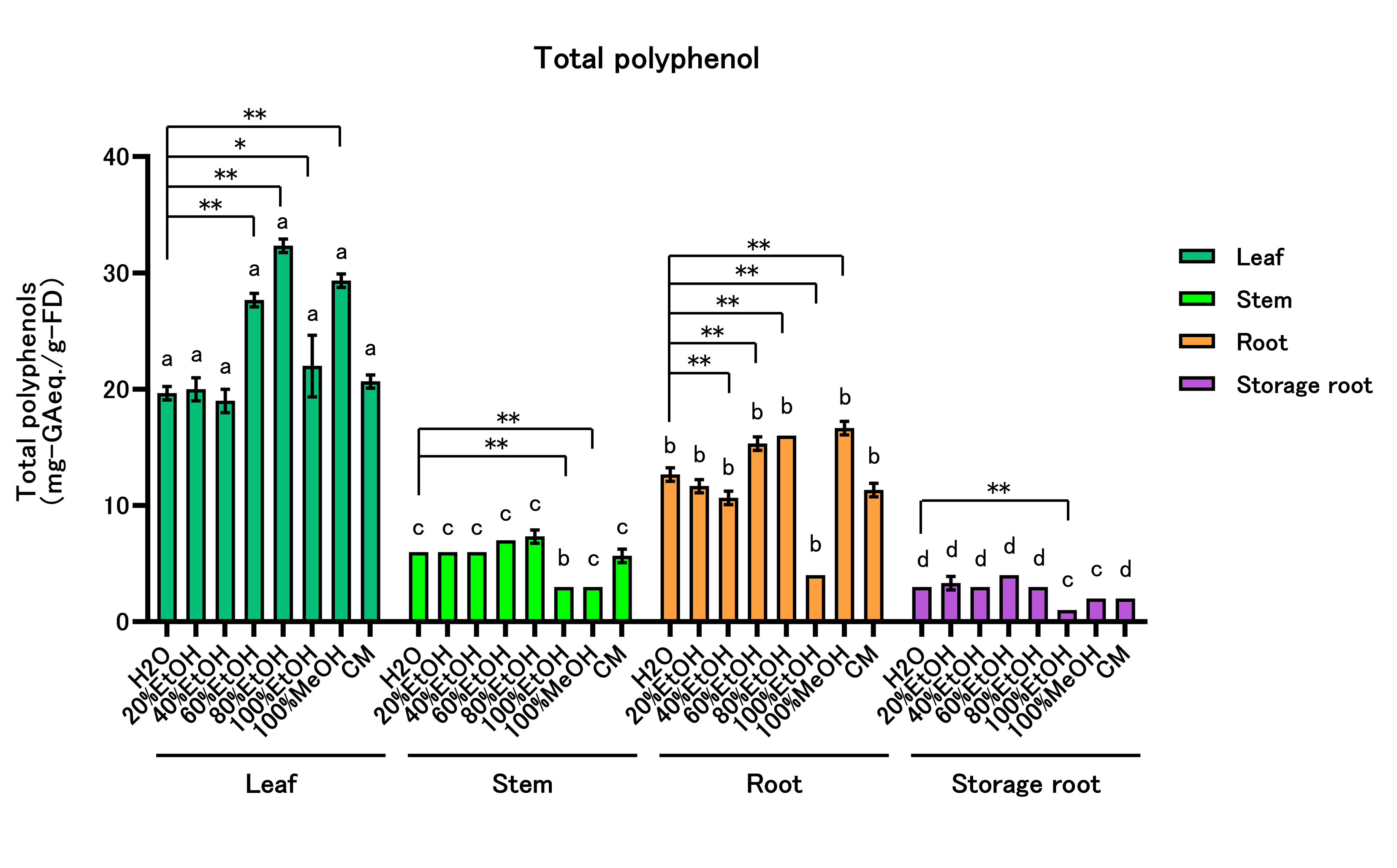

Caffeic acid (CA) content was quantified for all extracts (Figure 3; Supplemental Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, CA content was highest in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems and roots, CA peaked in 100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In storage roots, CA was highest in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: CA content ranked leaf > storage root > stem = root in 60%, 80%, and 100% EtOH; leaf > storage root > root > stem in 100% MeOH; and leaf > root > storage root > stem in CM.

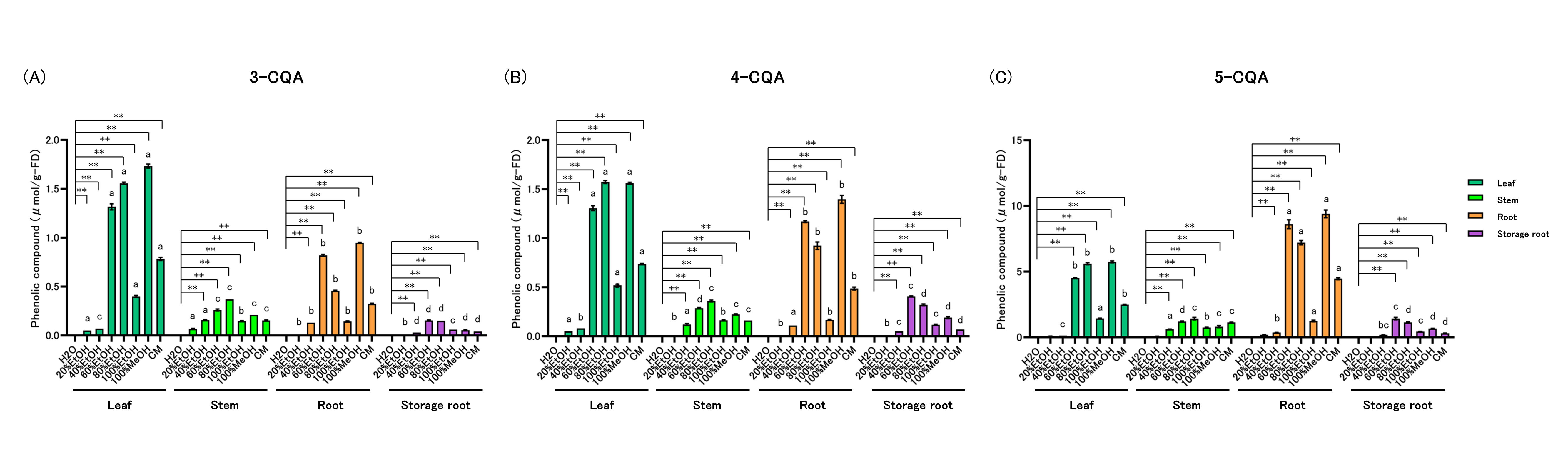

Levels of 3-CQA (3-O-caffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 4A, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, 3-CQA was highest in 20–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems, roots, and storage roots, 3-CQA peaked in 40–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 20% EtOH, leaf = stem > root = storage root. In 40% EtOH, stem > root > leaf > storage root. In 60% and 80% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM, leaf > root > stem > storage root. In 100% EtOH, leaf > stem = root > storage root.

Levels of 4-CQA (4-O-caffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 4B, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, 4-CQA was highest in 20–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems, roots, and storage roots, 4-CQA peaked in 40–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 20% EtOH, leaf > stem = root = storage root. In 40% EtOH, root > leaf = stem = storage root. In 60% EtOH, leaf > root > stem = storage root. In 80% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM, leaf > root > stem > storage root. In 100% EtOH, leaf > stem = root > storage root.

Levels of 5-CQA (5-O-caffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 4C, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves and storage roots, 5-CQA was higher in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems and roots, 5-CQA was higher in 40–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 40% EtOH, stems showed the highest 5-CQA among the parts (others lower). In 60% EtOH, root > leaf > stem = storage root. In 80% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM, root > leaf > stem > storage root. In 100% EtOH, leaf = stem > root > storage root.

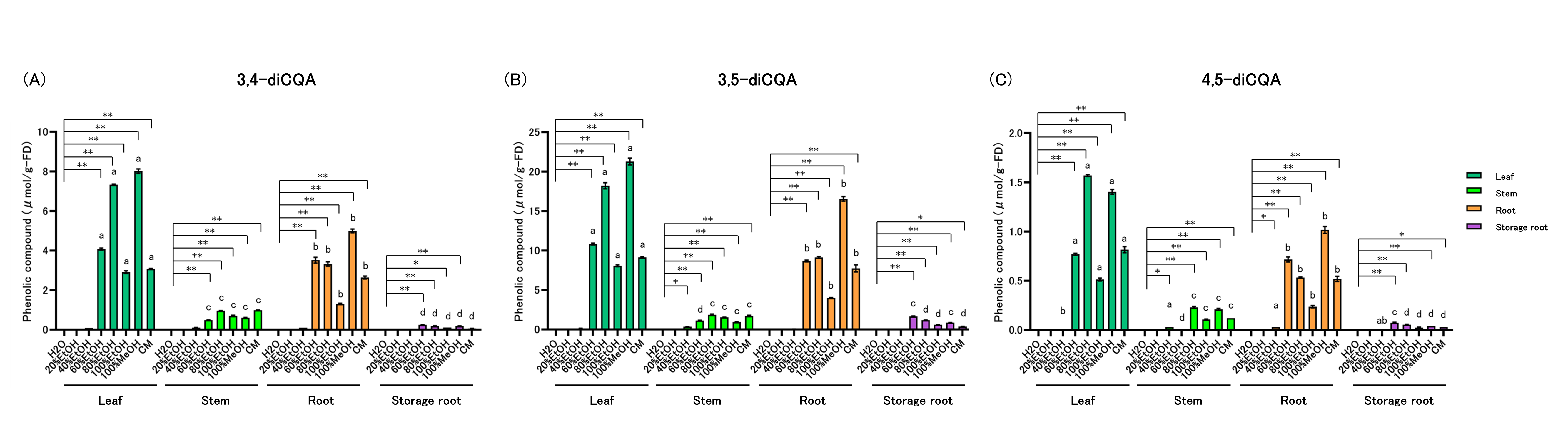

Levels of 3,4-diCQA (3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 5A, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, stems, and roots, 3,4-diCQA was highest in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In storage roots, 3,4-diCQA was highest in 60–100% EtOH and 100% MeOH. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 60%, 80%, and 100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM, the order was leaf > root > stem > storage root.

Levels of 3,5-diCQA (3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 5B, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, roots, and storage roots, 3,5-diCQA was highest in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems, 3,5-diCQA peaked in 40–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 60% EtOH, leaf > root > storage root > stem. In 80% EtOH, 100% EtOH, and CM, leaf > root > stem > storage root. In 100% MeOH, leaf > root > stem = storage root.

Levels of 4,5-diCQA (4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid) were quantified (Figure 5C, Supplementary Table 4). Within-part solvent effects: In leaves, 4,5-diCQA was higher in 60–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In stems, levels were higher in 40%, 80%, and 100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In roots, levels were higher in 20–100% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. In storage roots, levels were higher in 60% and 80% EtOH, 100% MeOH, and CM. Across-part rankings within each solvent: In 40% EtOH, stems and roots exceeded leaves. In 60% EtOH, leaf > root > storage root > stem. In 80% and 100% EtOH and in 100% MeOH and CM, leaf > root > stem > storage root.

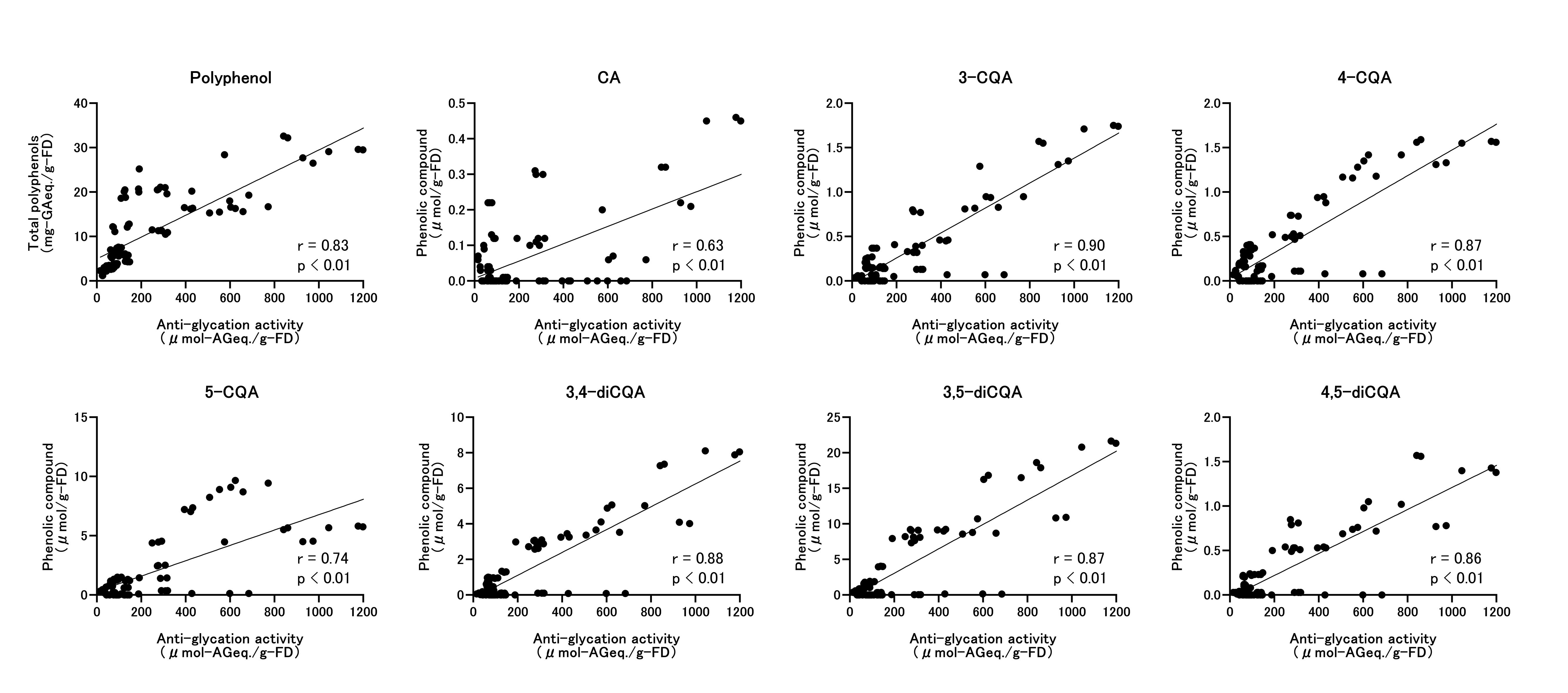

We then examined associations between antiglycation activity and total polyphenols and individual phenolics (Figure 6). Spearman’s correlations were high for all variables: TPC, r = 0.83 (p < 0.01); CA, r=0.63 (p < 0.01); 3-CQA, r=0.90 (p < 0.01); 4-CQA, r=0.87 (p < 0.01); 5-CQA, r=0.74 (p < 0.01); 3,4-diCQA, r=0.88 (p < 0.01); 3,5-diCQA, r=0.87 (p < 0.01); and 4,5-diCQA, r=0.86 (p < 0.01).

Using authentic standards, we confirmed antiglycation activity for each phenolic. All compounds exceeded aminoguanidine (AG), and diCQA species were more active than mono-CQAs (Supplementary Table 5). To assess the contribution of each phenolic, we conducted multiple regression; diCQA showed a significant positive association with antiglycation activity (Table 1).

Discussion

In this study, we prepared extracts from different sweet potato parts using a panel of solvents and evaluated their antiglycation activity. Leaves and roots showed strong activity, and diCQAs emerged as the principal contributors. Prior work has shown that green tea catechins and coffee chlorogenic acid suppress AGE formation [5, 6]. Our results extend this evidence by showing that CQAs abundant in sweet potato also inhibit glycation, indicating additional functionality of sweet potato–derived polyphenols. Across parts, leaves and roots were consistently more active than stems and storage roots, likely reflecting differences in the total polyphenol content and CQA profiles, as supported by the correlation and regression analyses. In particular, both leaves and roots contained high levels of 5-CQA, 3,5-diCQA, and 3,4-diCQA, mirroring their similar activity patterns.

Prior studies report that sweet potato leaves contain more polyphenols than storage roots and peels [18, 19]. In our survey of various solvents, leaves also showed a high total polyphenol content (TPC). The predominant leaf polyphenols were phenolic acids and flavonoids [20, 21]. Among phenolic acids, mono-, di-, and tri-O-caffeoylquinic acids and caffeic acid (CA) predominate, with 3,5-diCQA frequently identified by HPLC as the major constituent [20, 22]. A review reports 3,5-diCQA at 37.90–59.50% in leaves [18]. In sweet potato root peels, major polyphenols include chlorogenic acid (5-CQA; 112.24 mg/100 g DW), elliptochlorogenic acid (46.28 mg/100 g DW), 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (36.02 mg/100 g DW), 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (28.01 mg/100 g DW), and vanillic acid (22.68 mg/100 g DW) [23]. Consistent with these reports, we observed abundant 3,5-diCQA in leaves across solvents, and roots were rich in 5-CQA.

Polyphenols are extensively studied as antiglycation agents [24-26]. Their effects are attributed mainly to antioxidant and dicarbonyl-trapping activities. They suppress AGE formation by chelating transition metals, scavenging radicals, and reducing oxidative stress, as well as by trapping reactive carbonyl species generated at intermediate stages of glycation [27]. In our dataset, antiglycation activity correlated strongly with total polyphenol content and with individual phenolics, consistent with a role for phenolic hydroxyl groups in this process. Although the Folin–Ciocalteu assay is simple, reproducible, and widely used for plant matrices, it is nonspecific: aromatic amines, high sugar levels, and reducing agents such as ascorbate can inflate apparent totals [14, 28, 29]. These matrix effects should be minimized or corrected. Across the phenolics tested, activity ranked diCQA > CQA ≈ CA, indicating that a larger number of caffeic acid units tends to increase activity. diCQAs contain two catechol (o-diphenol) moieties and could act through multiple pathways: (i) Enhanced radical scavenging, (ii) Inhibition of Fenton-type reactions via metal chelation, and (iii) Trapping of reactive carbonyl species such as methylglyoxal (MGO) [4].

Because glycation proceeds through oxidation, dehydration, and condensation pathways, diCQAs likely exert a strong effect by attenuating oxidative steps and inactivating carbonyl intermediates. By contrast, differences between the 3-/4-/5-CQA positional isomers were small, suggesting that activity is driven primarily by the number of caffeic acid units rather than the esterification position.

The solubility of phenolics depends on the plant matrix and the polarity of the extraction solvent. Plant materials contain phenolics ranging from simple phenolic acids and anthocyanins to oligomeric and polymeric tannins (proanthocyanidins) [14]. Phenolics may also be bound to carbohydrates or proteins; thus, no single protocol is optimal for all targets. Commonly used solvents include methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, and their mixtures [14]. The solvent choice markedly affects the yield of extracted polyphenols [30], and aqueous mixtures (hot or cold) of ethanol, methanol, acetone, or ethyl acetate are often the most effective [31]. In practice, methanol and ethanol are widely used to extract antioxidant compounds from plant foods [13], with ethanol favored for food applications because of its safety [32]. Aqueous solvent systems e.g., 80% (v/v) methanol or ethanol often show higher antioxidant activity and phenolic content [13]. Consistent with these patterns, our data show that 80% EtOH and 100% MeOH yielded high levels of chlorogenic acids (CQAs) together with strong antiglycation activity. For translation to an industrial scale, solvent systems should balance extraction efficiency, cost, safety, and antiglycation performance; future work should assess food-grade ethanol–water systems and scalable operations.

This study has several limitations. First, our evaluation relied solely on an in vitro HAS glucose model and, therefore, does not capture absorption, metabolism, distribution, or interactions in vivo. Second, we quantified only fluorescent AGE formation and did not examine other glycation pathways or endpoints, such as dicarbonyl trapping or cross-linked/nonfluorescent AGEs. Future work should examine inhibition of carboxymethylarginine and pentosidine formation (e.g., by ELISA) and monitoring of glycation intermediates such as deoxyglucosone and glyoxal and potentially also methylglyoxal by HPLC. Third, the plant material was limited to a single cultivar (cv. Beniharuka) and one harvest year, precluding assessment of cultivar, environment, and year effects; indeed, total polyphenol content and phenolic profiles vary between sweet potato cultivars [33-35]. Comparative analyses across Japanese cultivars, regions, and years are warranted. Fourth, our quantification focused on CA/CQAs; we did not measure other phenolic classes (e.g., anthocyanins, flavonols, proanthocyanidins, or lignin-derived phenolics) or nonphenolic constituents that may influence glycation. Comprehensive profiling of these components will be crucial in clarifying the relationship between composition and antiglycation activity.

Conclusion

Solvent extracts from sweet potato leaves and roots showed the strongest antiglycation activity, with diCQAs identified as major contributors. These findings highlight the potential of sweet potato polyphenols for functional food development. Future studies should focus on processing stability, bioavailability, and in vivo efficacy to develop safe, food-grade antiglycation agents.

Author Contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. HM: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft. HS: Writing – review & editing. KI: Supervisor, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Calbee Inc.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Calbee Inc. The funder had the following involvement in the study: data analysis, interpretation of data, writing of this article. MS, HM, HS, and KI were employed by Calbee, Inc.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Calbee Kaistuka Sweet Potato, Inc. for providing us with Beniharuka sweet potatoes.

Supplementary Information

- Uceda AB, Mariño L, Casasnovas R, Adrover M (2024) An overview on glycation: molecular mechanisms, impact on proteins, pathogenesis, and inhibition. Biophys Rev. 16: 189-218.

- Rungratanawanich W, Qu Y, Wang X, Essa MM, Song BJ (2021) Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other adducts in aging-related diseases and alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Exp Mol Med. 53: 168-88.

- Thornalley PJ (2003) Use of aminoguanidine (Pimagedine) to prevent the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. Arch Biochem Biophys. 419: 31-40.

- Yeh WJ, Hsia SM, Lee WH, Wu CH (2017) Polyphenols with antiglycation activity and mechanisms of action: A review of recent findings. J Food Drug Anal. 25: 84-92.

- Wu Q, Li S, Li X, Fu X, Sui Y, et al. (2014) A significant inhibitory effect on advanced glycation end product formation by catechin as the major metabolite of lotus seedpod oligomeric procyanidins. Nutrients. 6: 3230-44.

- Kim J, Jeong IH, Kim CS, Lee YM, Kim JM, Kim JS (2011) Chlorogenic acid inhibits the formation of advanced glycation end products and associated protein cross-linking. Arch Pharm Res. 34: 495-500.

- Bovell-Benjamin AC (2007) Sweet potato: a review of its past, present, and future role in human nutrition. Adv Food Nutr Res. 52: 1-59.

- Ishida H, Suzuno H, Sugiyama N, Innami S, Tadokoro T, Maekawa A (2000) Nutritional evaluation on chemical components of leaves, stalks and stems of sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas Poir). Food Chemistry. 68: 359-67.

- Nabot M, Garcia C, Seguin M, Ricci J, Brabet C, Remize F (2024) Bioactive Compound Diversity in a Wide Panel of Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Cultivars: A Resource for Nutritional Food Development. Metabolites, 14.

- Phahlane CJ, Laurie SM, Shoko T, Manhivi VE, Sivakumar D (2022) Comparison of Caffeoylquinic Acids and Functional Properties of Domestic Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) Storage Roots with Established Overseas Varieties. Foods, 11.

- Suarsana I, Utama I, Arjentinia IPG, Kardena M (2018) Potential inhibition of glycation and free radical scavenging activities of purple sweet potato extracts. Bioscience Journal. 34: 1584-92.

- Park KH, Kim JR, Lee JS, Lee H, Cho KH (2010) Ethanol and water extract of purple sweet potato exhibits anti-atherosclerotic activity and inhibits protein glycation. J Med Food. 13: 91-8.

- Sultana B, Anwar F, Ashraf M (2009) Effect of extraction solvent/technique on the antioxidant activity of selected medicinal plant extracts. Molecules. 14: 2167-80.

- Dai J, Mumper RJ (2010) Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules. 15: 7313-52.

- Hori M, Yagi M, Nomoto K, Ichijo R, Shimode A, et al. (2012) Experimental Models for Advanced Glycation End Product Formation Using Albumin, Collagen, Elastin, Keratin and Proteoglycan.

- Pérez M, Dominguez-López I, Lamuela-Raventós RM (2023) The Chemistry behind the Folin-Ciocalteu Method for the Estimation of (Poly) phenol Content in Food: Total Phenolic Intake in a Mediterranean Dietary Pattern. J Agric Food Chem. 71: 17543-53.

- Sasaki K, Oki T, Kobayashi T, Kai Y, Okuno S (2014) Single-laboratory validation for the determination of caffeic acid and seven caffeoylquinic acids in sweet potato leaves. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 78: 2073-80.

- Liu T, Xie Q, Zhang M, Gu J, Huang D, Cao Q (2024) Reclaiming Agriceuticals from Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.) By-Products. Foods, 13.

- Truong VD, McFeeters RF, Thompson RT, Dean LL, Shofran B (2007) Phenolic acid content and composition in leaves and roots of common commercial sweetpotato (Ipomea batatas L.) cultivars in the United States. J Food Sci. 72: C343-9.

- Makori SI, Mu T-H, Sun H-N (2020) Total Polyphenol Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Individual Phenolic Composition of Different Edible Parts of 4 Sweet Potato Cultivars. Natural Product Communications 15: 1934578X20936931.

- Luo D, Mu T, Sun H (2021) Profiling of phenolic acids and flavonoids in sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves and evaluation of their anti-oxidant and hypoglycemic activities. Food Bioscience. 39: 100801.

- Sasaki K, Oki T, Kai Y, Nishiba Y, Okuno S (2015) Effect of repeated harvesting on the content of caffeic acid and seven species of caffeoylquinic acids in sweet potato leaves. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 79: 1308-14.

- Althawab S, Mousa H, Elzahar K, Mostafa A (2019) Protective Effect of Sweet Potato Peel against Oxidative Stress in Hyperlipidemic Albino Rats. Food and Nutrition Sciences. 10: 503-16.

- Turan-Demirci B, Gonen-Colak B, Buyuktuncer Z (2025) Exploring the Effects of Plant-Based Ingredients and Phytochemicals on the Formation of Advanced Glycation End Products in Bakery Products: A Systematic Review. Food Sci Nutr. 13: e70534.

- Shi B, Guo X, Liu H, Jiang K, Liu L, et al. (2024) Dissecting Maillard reaction production in fried foods: Formation mechanisms, sensory characteristic attribution, control strategy, and gut homeostasis regulation. Food Chem. 438: 137994.

- Khan M, Liu H, Wang J, Sun B (2020) Inhibitory effect of phenolic compounds and plant extracts on the formation of advance glycation end products: A comprehensive review. Food Res Int. 130: 108933.

- Wu CH, Huang SM, Lin JA, Yen GC (2011) Inhibition of advanced glycation endproduct formation by foodstuffs. Food Funct. 2: 224-34.

- Singleton VL, Orthofer R, Lamuela-Raventós RM (1999) [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. Methods in Enzymology: Academic Press: 152-78.

- Ainsworth EA, Gillespie KM (2007) Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat Protoc. 2: 875-7.

- Xu BJ, Chang SK (2007) A comparative study on phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities of legumes as affected by extraction solvents. J Food Sci 72: S159-66.

- Peschel W, Sánchez F, Diekmann W, Plescher A, Gartzía I, et al. (2006) An industrial approach in the search of natural antioxidants from vegetable and fruit wastes. Food Chemistry. 97: 137-50.

- Shi J, Nawaz H, Pohorly J, Mittal G, Kakuda Y, Jiang Y (2007) Extraction of Polyphenolics from Plant Material for Functional Foods—Engineering and Technology. Food Reviews International. 21: 139–66.

- Xu W, Liu L, Hu B, Sun Y, Ye H, et al. (2010) TPC in the leaves of 116 sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) varieties and Pushu 53 leaf extracts. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 23: 599-604.

- Zhao D, Zhao L, Liu Y, Zhang A, Xiao S, et al. (2022) Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of the Flavonoid Biosynthetic Pathway for the Accumulation of Anthocyanins and Other Flavonoids in Sweetpotato Root Skin and Leaf Vein Base. J Agric Food Chem. 70: 2574-88.

- Sun H, Mu T, Xi L, Zhang M, Chen J (2014) Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) leaves as nutritional and functional foods. Food Chem. 156: 380-9.

Tables at a glance

Figures at a glance