Surgery Followed by Chemotherapy Versus Definitive Concurrent Chemo-radiotherapy for Stage IIIA Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

Received Date: February 04, 2023 Accepted Date: March 04, 2023 Published Date: March 06, 2023

doi: 10.17303/jlpm.2022.2.101

Citation: Ivane Kiladze, Vladimer Kutchava, Merab Kiladze (2023) Surgery followed by chemotherapy versus definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy for stage IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Lung Dis Pulm Med 2: 1-12

Abstract

Introduction: Treatment of stage IIIA NSCLC continues to be challenging, there are no definitively proven optimal approaches and treatment selection in a multidisciplinary team meeting is of paramount importance.We compared stage IIIA patients who were treated with resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with patients who received definitive chemoradiotherapy (CH-RT).

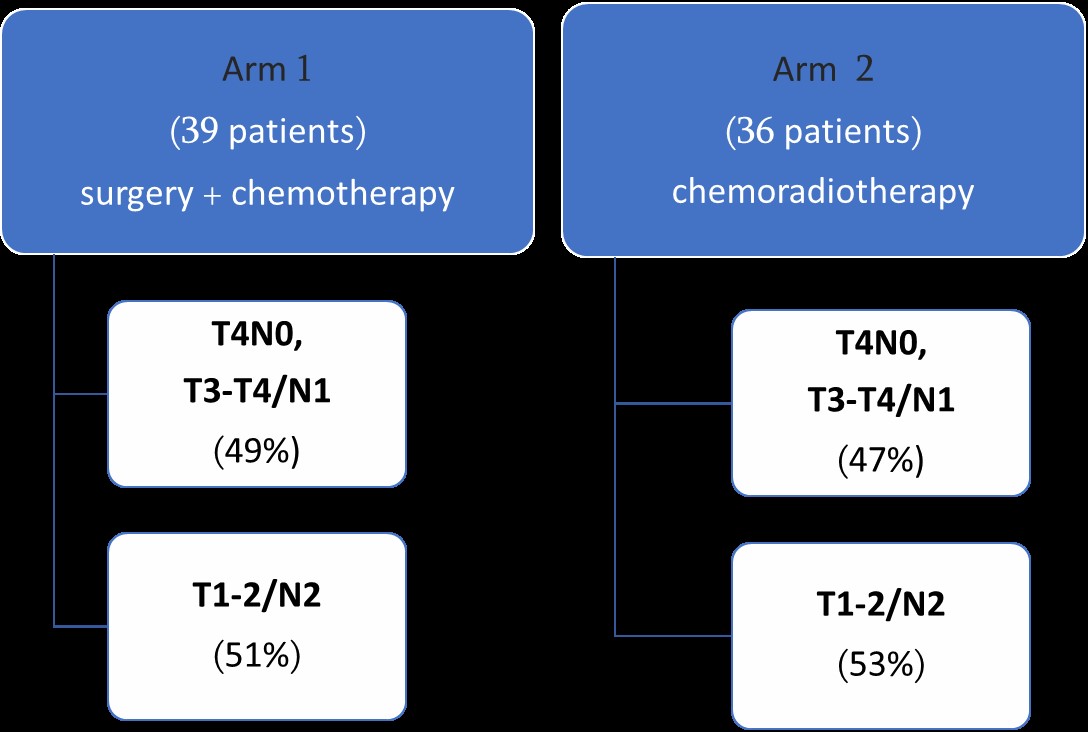

Material and Methods: This retrospective study is based on 75 patients attending two cancer centers in Tbilisi between 2014 and 2016. Patients were treated either with resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (Surgical arm) or a regimen of chemoradiation alone (CHRT arm). Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare survival outcomes between groups, as well as treatment complications were analyzed

Results: The medical records of 75 patients (39 surgical arm and 36 CHRT arm) were reviewed. The The median age was 60 (56.1-62.0) and 63 (58.7-63.9) in surgical and CHRT arms respectively. More than half of patients in both arms were with squamous cell histological type (46% and 58% respectively).

The extent of surgical resection was lobar or greater. (15 lobectomies and 24 pneumonectomies). All patients had undergone complete mediastinal lymph node dissection.

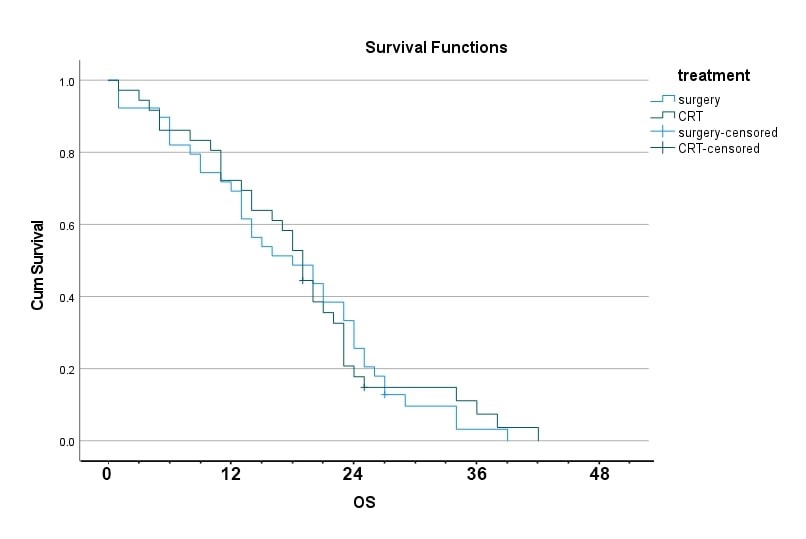

Median survival in surgical arm was 18.0 month (95% confidence interval, 10.6-25.3) compared to 19.0 month (95% confidence interval, 16.6-21.3) in CHRT arm and this difference was not statistically significant. No difference in the 1-year survival was observed between surgical and CHRT arms (69% vs 64%, respectively. p= 0.623).

In CHRT arm most common adverse event was esophagitis (Grade 2) in 16 (44.4%) patients. In surgical arm only one severe bleeding developed and reoperation was performed. Two patients had wound healing problems. Within 1 month 5 treatment related deaths occurred: 3 patients in the surgical arm (two pulmonary embolus and one cardiac complication) and 2 patients in CHRT arm (two pulmonary embolus). In terms of treatment complications, no statistically significant difference was found among the treatment arms

Conclusions: The authors acknowledge that one multimodality treatment has not been shown to be superior to another and conclude the benefits and harms are fairly closely matched. A treatment strategy with primary surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy is neither clearly better nor clearly worse than chemoradiotherapy.

These results seem to indicate definitive chemoradiotherapy as the treatment of choice for stage IIIA NSCLC in selected patients. Non-surgical treatment can be used with equal effectiveness and can be considered in special population with poor PS and comorbidities. Our data highlight the need to develop new criteria for better selection patients for surgical and non-surgical treatment. Further prospective studies are of paramount importance to address this issue.

Keywords: Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC), Chemoradiotherapy, Surgery, Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Introduction

In 2018 lung cancer (LC) was the most common malignancy and deaths from LC exceed those from any other malignancy worldwide [1].

Approximately 30% of patients affected with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are diagnosed with locally advanced disease (Stage III). This is a heterogenous group that ranges from stages IIIA and IIIB, to stage IIIC (TNM staging 8th edition) [2,3].

Stage IIIA LC patients represent a heterogeneous group with a diversity of tumor characteristics and varying degrees of lymph node involvement ranging from N1 and unsuspected N2 disease only detected by intraoperatively to conglomerate, bulky and invasive, unresectable N2 disease. An estimated 15% of LC patients present with stage IIIA NSCLC [4]. For unresectable N2 NSCLC the standard of care in the context of appropriate physiological reserve is concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CHRT) with a platinum doublet which is nowadays frequently followed by conso- lidation Durvalumab [5].

The optimal treatment strategy of potentially resectable stage IIIA disease group is keenly debated regarding the best strategy, including surgery with either adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemo- and/or radiotherapy (RT) or definitive concurrent CHRT and several other strategies [6]. Surgical treatment of stage IIIA NSCLC remains a controversial area in the management of lung cancer despite being considered as part of combined modality therapy over the last two decades [7].

In operable stage IIIA, induction or adjuvant chemotherapy improve overall survival and are established as standard treatments [8,9] There is evidence that management of NSCLC stage III varies between countries, geographical regions, cancer centers and even treating physicians. Reasons for these variations include differences in regional standards, access to diagnostic procedures as well as therapeutic modalities, and resources. [10,11] However, the best treatment strategy for stage IIIA NSCLC has not been determined and physicians and other specialists typically have discussions on a case-by-case basis to decide the best strategy for these patients.

Based on above controversies we conducted study focusing on treatment of stage IIIA patients (T4N0-1, T3N1, T1-2N2). The current investigation evaluated survival outcomes and adverse events of treatment among stage IIIA NSCLC patients receiving 2 different treatment modalities, resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy versus definitive CHRT alone.

Methods

This retrospective study is based on 75 patients attending two cancer centers in Tbilisi, Georgia between 2014 and 2016. Patients were treated either with resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (Surgical arm) or a definitive chemoradiation (CHRT arm). [Figure 1] Medical records were reviewed and only patients with clinically staged IIIA disease were included.

Database included age, gender, tumor size, treatment modality (surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy or definitive CHRT), tumor type (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, or other type), lymph node involvement/staging, treatment complications and survival time.

All patients initially underwent chest/abdominal CT (or in some cases positron emission tomo- graphy/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan), with bronchoscopy +/- endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopy. Eligible patients had previously untreated, histologically or cytologically proven NSCLC, considered resectable by the local multidisciplinary team in accordance with local institutional policies. Patients could be any age, with WHO performance status 0–2, and no evidence of distant metastases. Patients had to be deemed fit for chemotherapy and the proposed surgical treatment, and have no other or previous malignancy. Overall survival for both groups was compared beginning at the date of starting treatment.

In surgical arm patients underwent surgery-lobectomy/bilobectomy or pneumonectomy followed by 4 cycles of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. In CHRT arm reasons for deciding not to undergo surgery was patients’ refusal (30 out of 36) or possible risks of expected complications of surgical interventions, because of comorbidities (6/36). In this arm patients were treated with definitive CHRT, which included RT 60-66 Gy in 30-33 daily fractions with platinum-based chemotherapy (6 cycles of carboplatin AUC=2.0 and paclitaxel 50 mg/m2 /week or cisplatin 50 mg/m2 on days 1,8, 29 and 36 plus etoposide 50 mg/m2 days 1-5 and 29-33).

In surgical arm most cases with N2 disease were unexpected N2 after thorough preoperative staging or “surprise” N2 identified during surgery. In CHRT arm we identified patients eligible for surgery, but due to some reasons (patients’ choice, accompanied comorbidities, refuse for surgical intervention) they were treated by definitive chemoradiotherapy.

The purpose of our study was to compare effectiveness of primary surgery and chemotherapy versus CHRT in patients with stage IIIA NSCLC. We evaluated the survival parameters and treatment complications.

Statistical Analyses

The main objective of the research was the determination of survival outcomes (median overall survival and 1-year overall survival) and adverse events of treatment.

Overall survival for both groups was compared beginning at the date of starting treatment. Survival was assessed from the date of starting treatment until the patient died of any cause. The date of starting treatment for surgical arm was the day of surgery and for CHRT arm the first day of concomitant chemoradiation. Treatment safety was assessed according to the NCI- Common Toxicity Criteria version (CTCAE). Treatment related death was measured as death within 30 days after finishing surgical intervention or chemoradiotherapy in surgical and CHRT arms, respectively.

All statistical tests were two sided, and a p value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to display and evaluate the differences in survival outcomes between groups. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented. SPSS version 21 was used to conduct these analyses.

Results

The medical records of 75 patients (39 surgical arm and 36 CHRT arm) were reviewed. The median age was 60 (56.1-62.0) and 63 (58.7-63.9) in surgical and CHRT arms respectively. In both groups ~90% of patients were males. Of the analyzable patients, in surgical arm 92% and in CHRT arm 89% had performance score ECOG 0-1. Squamous cell histological type was most common in both arms (46% and 58% in surgical and CHRT arms, respectively).

By staging subcategories, T2N2 disease was most frequent in both arms (46% and 47 %, in surgical and CHRT arms respectively). More T3N1 tumours were treated in surgical arm (34% vs 14%) and in CHRT arm T4N1disease predominance was observed (27% vs 10%). This difference was not statistically significant. [Table #1]

The extent of surgical resection was lobar or greater. (15 lobectomies and 24 pneumonectomies). All patients had undergone complete mediastinal lymph node dissection. In CHRT arm chemotherapy regimen of cisplatin/etoposide was used in 22 (61%) and carboplatin/ paclitaxel in 14 (39%) patients.

Median survival in surgical arm was 18.0 month (95% confidence interval, 10.6-25.3) compared to 19.0 month (95% confidence interval, 16.6-21.3) in CHRT arm and this difference was not statistically significant [Figure 2]. No difference in the 1-year survival was observed between surgical and CHRT arms (69% vs 64%, respectively. p= 0.623). [Table #2]

In CHRT arm most common adverse event was esophagitis (Grade 2) in 16 (44.4%) patients. In surgical arm only one severe bleeding developed and reoperation was performed. Two patients had wound healing problems. Within 1 month 5 treatment related deaths occurred: 3 patients in the surgical arm (two pulmonary embolus and one cardiac complication) and 2 patients in CHRT arm (two pulmonary embolus). In terms of hematological complications, no statistically significant difference was found between the treatment arms. [Table #3] Non-hematological complications were different which is explainable, as Grade > 2 esophagitis and pneumonitis were only observed in CHRT arm

Discussion

We conducted study which compares face to face two different treatment modalities, resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy versus definitive CHRT alone. To our knowledge our study is the first of such kind in the literature.

Our database included age, gender, tumor size, treatment modality (surgery plus adjuvant chemotherapy or definitive CHRT), tumor type (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, or other type), lymph node involvement/staging. We evaluated survival outcomes (1 -year survival and median overall survival) and adverse events in both groups and compared them. We included patients with ECOG-2, which is exclusion criteria in majority of studies.

Our study did not show survival benefit among patients receiving surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy compare to patients receiving chemoradiation alone. Difference was not observed for treatment complications as well.

The management of stage IIIA lung cancer remains controversial. Many controversies are caused by the heterogeneity of presentation at diagnosis. With various extents of lung tumor, nodal status and co-morbidities, different approaches have been adopted. [12]. With this background of individual risk profiles and different morphological tumor presentation on one hand, and different treatment strategies on the other, the patient with stage III disease should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team including pulmonologists, thoracic/ medical oncologists, radiation oncologists and thoracic surgeons [13]

Current treatment modalities typically include surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, neoadjuvant therapy followed by surgical resection, or definitive chemoradiation; however, to date a consensus has not been reached as to which approach is most efficacious [14].

Our study in surgical arm included patients with unexpected or unforeseen or “surprise” N2 disease, and potentially resectable N2 involvement. It should already be noted that there is no universally accepted definition of “potentially resectable N2,” which is center and the experience thoracic surgeon dependent. Thoracic surgery for stage III disease may imply extensive operations including sleeve resections and resection of locally invaded mediastinal organs (e.g. trachea, vena cava, vertebra, pericardium, parts of the right atrium) [15]. Accurate preoperative staging of mediastinal lymph nodes is of paramount importance and despite modern high technology investigations in some patients N2 involvement is identified intraoperatively. For this group of patients if a complete resection can be achieved, major pulmonary resection with mediastinal lymph nodes dissection should proceed as planned. [16] This was investigated in the past by different prospective randomized trials. [17-20] Nevertheless, a benefit in overall survival (OS) was never demonstrated. It is generally accepted that patients with non-bulky (defined as less than 3 cm), discrete, or single-level N2 involvement may be the best candidates to undergo resection as part of a multimodality approach.

The distinction between single-zone and multi- zone N2 disease is a critical factor for decision of surgical treatment. Analysis of the International Asso- ciation for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) staging databases revealed that patients with single-station N2 disease have a similar 5-year survival to those with multistation N1 disease (approximately 35% 5-year survival) but a much better survival than those with multistation N2 disease (20% 5-year survival).[21] Given that N1 disease is considered a primarily surgically managed disease, these results have been interpreted by some to indicate that single-station or single-zone N2 disease should also be managed primarily by surgery.

Several meta-analyses performed on the subject of role of surgery in IIIA/N2 disease tried to provide more definite answers, but did not reach similar conclusions. McElnay and colleagues compared bimodality and trimodality regimens including six trials (n=868 patients), showed that the outcome for the radiotherapy and surgical arms were similar for bimodality regimens, but with 13% survival advantage for surgical intervention within combined trimodality therapy [22]. This does not reflect a selection bias as in both arms patients qualified for surgical resection. However, the latter difference was not statistically significant. Conclusions of the most recent meta-analysis including randomized trials that compared surgery with radiotherapy as local treatment modalities were more moderate, showing no difference in overall and prog- ression-free survival between surgery and radiotherapy in stage III NSCLC [23]. Our study shows similar results for OS.

The majority of guidelines agree that in potentially resectable stage IIIA NSCLC multimodality treatment is the standard of care using chemotherapy for distant disease control and either surgery, radiotherapy or a combination of both for local control. The evidence base confirms that no one treatment regimen has been shown superior to another [24]. However, the surgical management of stage IIIA NSCLC remains highly controversial in various guidelines. Some of them supporting preoperative chemotherapy over adjuvant chemotherapy [25-26] based on evidence comparing not preoperative versus post- operative chemotherapy, but preoperative chemotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone, and not specifically in patients with resectable N2 NSCLC. The fact that giving chemotherapy and surgery is better than surgery alone does not answer the question as to whether chemotherapy should be given before or after surgery.

ESMO guideline recommends surgical-based multimodality treatment in single-station N2 disease. However, this is an ‘optional’ recommendation due to insufficient evidence. Definitive CHRT is ‘preferred’ in multistation but resectable N2 NSCLC [27]. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guideline recommends that potentially resectable N2 NSCLC can be managed with definitive CHRT or induction chemotherapy followed by surgery or induction CHRT followed by surgery. It also recommends that patients undergoing definitive CHRT should proceed with maintenance durvalumab subsequently [28]. The guideline is clear that patients with resectable N2 NSCLC should not be excluded from surgery as some will achieve a long-term survival.

In our study all patients in surgical arm where treated by adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy based on NSCLC meta-analysis combined the results from eight randomised trials of surgery versus surgery plus adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy, showing a small, but not significant (p=0•08), absolute survival benefit of around 5% at 5 years (from 50% to 55%) [29].

Our study didn’t show superiority of surgical combined treatment over definitive CHRT similar to current trials which didn’t show any evidence of the superiority of a surgical combined treatment, compared with definitive CHRT [21-24]. Definitive CHRT can be offered, rather concurrent than sequential [30], with radiation doses up to 60 Gy.

Based on the finding of a comparable outcome in survival in the randomized trials, [21-24] many institutions prefer the safer approach of CHRT. However, surgery may represent a good treatment choice within a multimodality treatment program for patients in good condition and upfront potentially resectable tumors provided that patients will be treated by an expert team incorporating all disciplines of thoracic oncology ensuring a high level of expertise [31].

Two modern randomized studies have been published comparing concurrent CHRT treatments with and without surgery. In the Intergroup 0139 trial [32], patients with stage III/N2 disease were treated with concurrent induction chemotherapy plus RT, followed by surgery (surgical arm) or radiotherapy. A total of 396 eligible patients were randomized and there were no differences in OS between the two groups. However, in an exploratory analysis, survival was improved for the patients who underwent lobectomy, but not pneumonectomy, compared with definitive concurrent CHRT. In the ESPATUE trial [33] patients with resectable stage IIIA-N2 and selected stage IIIB NSCLC were randomized to surgery or definitive concurrent CHRT boost after induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent CHRT. A total of 245 eligible patients were recruited to induction therapy over a 10-year period. There was no difference in OS between the arms. Although both trials were planned to demonstrate superiority in the surgery arm, they failed to show any benefit from surgery in terms of OS.

Although the concurrent chemotherapy and radiation (CHRT) is considered the standard care, the optimal chemotherapy regimen remains unclear. The two most commonly used concurrent regimens are etoposide-cisplatin (EP) and weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel (PC) regimens with nearly similar survival results and different toxicity profile [30]. In our study more patients received etoposide-cisplatin (EP) chemotherapy as part of CHRT treatment 22 patients (61%) compared to weekly carboplatin/paclitaxel (PC) regimen 14 (39%), but this difference was not statistically significant. Also, aim of our study was not comparing of chemotherapy regimens.

Concurrent CHRT is associated with higher rates of radiation esophagitis, which is largely reversible, but there is no increase in the risk of radiation-related lung toxicity [30]. The incidence of grade 2-3 esophagitis in our study was observed in 16 (44.4%) patients. Grade 3 esophagitis was observed in 9 patients (25%) which is similar to study by Liang and colleagues in which the incidence of grade 3 esophagitis was 26% [34]. In our study in CHRT arm incidence of Grade 2 or more radiation pneumonitis was observed in 10 (27.7%) cases. In CHRT arm, treatment-related death was observed in 2 (5.5%) patients which is similar to Asian study (4.7%) [34].

Advanced age is a well-recognized factor of clinical limitations. As age increases, there is a decline in physiological reserve, functional status and cognition, whereas comorbidities tend to increase. Our study includes 7 patients with ECOG 2 (3 (8%) in surgical arm and 4(11%)) in CHRT arms. This gives study more confidence as majority of studies ECOG 2 is exclusion criteria. We don’t identify ECOG score as independent ‘unfavorable’ prognostic factor.

The results of our study should be interpreted with caution due to its retrospective nature which does not allow to control the selection in treatment allocation. In addition, there is a lack of information on resection R0 vs R1, and disease free or progression free survival.

There is lack of the best treatment strategy for stage IIIA NSCLC and typically treatment is based on various factors including patient’s performance status, spread of primary tumour, involvement of lymph nodes and expertise of cancer centres and even thoracic surgeons. It is very clear that multimodality treatment is complex and should be done in expert and high-volume centres with decision-making through an equally experienced MDT.

Comment

The authors acknowledge that one multimodality treatment has not been shown to be superior to another and conclude the benefits and harms are fairly closely matched. A treatment strategy with primary surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy is neither clearly better nor clearly worse than chemoradiotherapy.

These results seem to indicate definitive chemoradiotherapy as the treatment of choice for stage IIIA NSCLC in selected patients. Non-surgical treatment can be used with equal effectiveness and can be considered in special population with poor PS and comorbidities. Our data highlight the need to develop new criteria for better selection patients for surgical and non-surgical treatment. Further prospective studies are of paramount importance to address this issue.

Acknowledgements

Authors thanks to Dr. I. Donguzashvili for technical support

Funding statement

There has been no funding for this study

Conflict of Interest

The Authors Declare No Competing Interests Regarding This Study

Acknowledgments

Authors thanks to Dr. I. Donguzashvili for technical support

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I et al. (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68: 394-424.

- Detterbeck FC, Boffa DJ, Kim AW et al. (2017) The eighth edition lung cancer stage classification Chest 151: 193-203.

- Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, Travis WD et al. (2017) Lung cancer—major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin 67: 138-55.

- Surveillance, epidemiology and end results: (2010) US National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aggarwal C et al. (2019) NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17: 1464-72.

- I Kiladze, M Kiladze, B Jeremic (2021) Neoadjuvant Treatment for Resectable, Stage IIIA Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Canc Therapy & Oncol Int J 17: 555974.

- Patel AP, Crabtree TD, Bell JM et al. (2014) National patterns of care and outcomes after combined modality therapy for stage IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 9: 612-21.

- Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV et al. (2008) Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE collaborative group. J Clin Oncol 26: 3552-9.

- NSCLC (2014) Meta-analysis Collaborative Group. Preoperative chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 383: 1561-71.

- Zemanova M, Pirker R, Petruzelka L, Zbozínkova Z et al. (2020) Care of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer stage III - the Central European real-world experience. Radiol Oncol 54: 209-20.

- Kiladze I, Mariamidze E, Jeremic B (2020) Lung Cancer in Georgia. J Thorac Oncol 15: 1113-8.

- Darling GE, Li F, Patsios D et al. (2015) Neoadjuvant chemoradiation and surgery improves survival outcomes compared with definitive chemoradiation in the treatment of stage IIIA N2 non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 48: 684-90

- Uy KL, Darling G, Xu W et al. (2007) Improved results of induction chemoradiation before surgical intervention for selected patients with stage IIIA-N2 nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 134: 188-93

- Veeramachaneni NK, Feins RH, Stephenson BJ et al. (2012) Management of stage IIIA non-small cell lung cancer by thoracic surgeons in North America. Ann Thorac Surg 94: 922-26

- Shi W, Zhang W, Sun H et al. (2012) Sleeve lobectomy versus pneumonectomy for non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol 10: 265.

- Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV et al. (2008) Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 26: 3552–9.

- Eberhardt WEE, Pöttgen C, Gauler TC et al. (2015) Phase III Study of Surgery Versus Definitive Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Boost in Patients With Resectable Stage IIIA(N2) and Selected IIIB Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer After Induction Chemotherapy and Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy (ESPATUE). J Clin Oncol 33: 4194-201.

- van Meerbeeck JP, Kramer GW, Van Schil PE et al. (2007) Randomized controlled trial of resection versus radiotherapy after induction chemotherapy in stage IIIA-N2 non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 442-50.

- Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VR et al. (2009) Phase III study of concurrent chemotherapy and full course radiotherapy (CT/RT) versus CT/RT followed by surgical resection for stage IIIA(pN2) non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): outcomes update of North American Intergroup 0139 (RTOG 9309). Lancet 374: 379-86.

- Pless M, Stupp R, Ris HB et al. (2015) Induction chemoradiation in stage IIIA/N2 non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet 386: 1049-56.

- Rusch VW, Crowley J, Giroux DJ et al. (2007) The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the N descriptors in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2: 603-12.

- McElnay PJ, Choong A, Jordan E et al. (2015) Outcome of surgery versus radiotherapy after induction treatment in patients with N2 disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Thorax 70: 764-8.

- Pottgen C, Eberhardt W, Stamatis G et al. (2017) Definitive radiochemotherapy versus surgery within multimodality treatment in stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) – a cumulative meta-analysis of the randomized evidence. Oncotarget 8: 41670-8.

- Evison M, McDonald F, Batchelor T (2018) What is the role of surgery in potentially resectable N2 non-small cell lung cancer? Thorax 73: 1105-9.

- Lim E, Baldwin D, Beckles M et al. (2010) Guidelines on the radical management of patients with lung cancer. Thorax 65: iii1-27.

- Ramnath N, Dilling TJ, Harris LJ et al. (2013) Treatment of stage III non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 143: e314S-40S.

- Eberhardt WE, De Ruysscher D, Weder W et al. (2019) 2nd ESMO Consensus conference in lung cancer: locally advanced stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 26: 1573-88.

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aggarwal C et al. (2019) NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17: 1464-72.

- Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group (1995) Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. BMJ 311: 899-909

- Aupérin A, Le Péchoux C, Rolland E et al. (2010) Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 28: 2181-90

- Pöttgen C, Eberhardt W, Stamatis G et al. (2017) Definitive radiochemotherapy versus surgery within multimodality treatment in stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) - a cumulative meta-analysis of the randomized evidence. Oncotarget 8: 41670-8.

- Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW et al. (2009) Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374: 379-86.

- Eberhardt WE, Pöttgen C, Gauler TC et al. (2015) Phase III Study of Surgery Versus Definitive Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy Boost in Patients With Resectable Stage IIIA(N2) and Selected IIIB Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer After Induction Chemotherapy and Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy (ESPATUE). J Clin Oncol 33: 4194-201

- Liang J, Bi N, Wu S et al. (2017) Etoposide and cisplatin versus paclitaxel and carboplatin with concurrent thoracic radiotherapy in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol 28: 777-83.

Tables at a glance

Figures at a glance