Setting Prioritisation for Medicinal Plant Conservation in Saudi Arabia

Received Date: May 24, 2024 Accepted Date: June 24, 2024 Published Date: June 27, 2024

doi: 10.17303/jmph.2024.3.201

Citation: Ibrahim Jamaan Alzahrani, Joana Magos Brehm, Nigel Maxted (2024) Setting Prioritisation for Medicinal Plant Conservation in Saudi Arabia. J Med Plant Herbs 3: 1-20

Abstract

Traditional medicine is an important part of cultural heritage and was widely used in Saudi Arabia before the introduction of biomedicine, and it is still much used in the present. This study was conducted to create a medicinal plant checklist and a priority list for active conservation in Saudi Arabia. The checklist includes 1174 MP taxa of medicinal plants, consisting of 1100 species and 74 subspecific taxa within 122 families and 607 genera, including 1045 native (89.01%) and 129 introduced taxa (10.99%). An inventory was compiled using a variety of published resources. This inventory was prioritised using a serial method and four criteria: traditional use, native status, threat status, and legal use. The prioritised inventory for Saudi Arabia includes 74 species of medicinal plants from 35 families and 69 genera. These priority medicinal plant species necessitate additional research on in situ and ex situ conservation measures, as well as public education about the significance of medicinal plant conservation.

Keywords: Medicinal Plants; Priority List; In Situ; Ex Situ; Conservation; Saudi Arabia

Introduction

There is a long tradition of plants and herbs with medicinal properties being used by humans for healing purposes [1,2]. Plants are the source of a number of ancient medicines and may also be of new remedies [3]. There are 390,900 flowering plants worldwide [4], and over 50,000 of them have medicinal properties [5-8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), roughly 80% of the global human population depends upon herbal medicine, which are used in primary healthcare [3,9-13]. Moreover, the demand for herbal medicines is rising in developed countries, where many people think plants are safer and more effective than modern medicine because of their natural source and they are comparatively cheap [1,2,10].

Continued wild medicinal plant (MP) use is predicated on continued MP existence and MP species like any other wild plant species are subject to increased threats from human mismanagement of the environment. One of the most urgent issues facing the global conservation community is how to identify areas rich in biodiversity and allocate the limited resources available among regions to secure biodiversity for the future and initial, first step is species prioritization [14]. The conservation of MPs is gaining increasing attention due to the renewed interest in herbal medicines for healthcare around the world [15]. In the past decade, focus has been on identifying biodiversity hotspots and conservation gaps for endangered and endemic MP species [12]. This is essential to protect these species before their diversity is reduced, or they go extinct. Doing so should increase awareness of the importance of MPs amongst all stakeholders and stimulate the desire to protect this cultural heritage and natural resource, and clarify knowledge about their ecological requirements. Therefore, conservation planning is an important step in protecting the most threatened species and to avoid a major decline in the diversity of MPs [16].

The conservation and sustainable use of medicinal and aromatic plants has been widely researched [17-24], and many suggestions on conservation priorities have been put forward, including the establishment of coordinated systems that hold an inventory of species, monitor species status and record existing in situ and ex situ conservation practices [11]. The best way to conserve biodiversity is in situ as this protects the original habitat and the genetic diversity of species as well as allowing species to evolve in their natural environment [25]. In order to carry out in situ conservation, protected areas exist globally, and these represent a regulatory and management tool for conservation [26]. In addition, it is necessary to apply a number of complementary ex situ strategies, such as seed banks, botanical gardens and DNA banks, to ensure species conservation [27].

The Arabian Peninsula is rich in biodiversity and contains different ecosystems with diverse plant species, including a plethora of medicinal herbs, shrubs, and trees [2,27]. Saudi Arabia is about 1,969,000 km² and occupies two-thirds of the Arabian Peninsula [28]. It has a hot desert climate and little rainfall [1]. Traditional medicine is an important aspect of Saudi cultural heritage, which was widely used prior to the introduction of biomedicine [2,29] and is still relied upon by many in Saudi Arabia [30].

Out of a total of 2,250 species of Saudi flora [1,31], 300 are known medicinal species (12%), belonging to 72 families, with a further 1,950 species belonging to 142 families which still need to be investigated for their potential medicinal properties [31]. Saudi Arabia’s flora faces various and substantial threats, including irregular weather, heavy metals stress, salinity, changed soil pH, drought, extreme temperatures, and increased habitat fragmentation [27], many of which are associated with climate change. The number of endangered species is growing annually due to unfavourable environmental conditions and human mismanagement [32]. In addition, specifically for medicinal plants there is only partial legislative or regulatory control over the use or manufacturing of local herbal medicines in Saudi Arabia [33]. Therefore, there is a great need and urgency for conservation, cultivation, and the sustainable use of important MP species to sustaining future and potential use [34].

In Saudi Arabia, as in other parts of the world, many plants are harvested by local communities without any regard for conservation. However, people collect and sell plants in local markets to make a living in the arid, mountainous environment [28]. The Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) has published a list of 131 MP species allowed to be sold in Saudi herbal markets, which includes only 42 native plant species distributed in Saudi Arabia [35]. MPs are a vital, healthy, and economic element of region-specific biodiversity ecosystem services. However, if the resource is to be maintained it is important to conduct a survey MP diversity to aid conservation planning and implementation and sustainable use [2,31]. The conservation of biodiversity became an important part of Saudi government policy as early as the 1970s, and the country became a signatory of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2001 [27]. Determining the priorities and standards for species conservation are the first important, necessary steps in the conservation process [36], MP prioritization may be based on several factors such as species richness, habitat, endemism, probability of species extinction, genetic diversity, economic value, and other indices [14].

Several authors from diverse countries have prioritised MPs, for example, Kala et al. [37] prioritised MP species in the Indian state of Uttaranchal based on four criteria: endemism, use value, mode of harvesting, and rarity status; Allen et al. [38] prioritised threatened native MP species in Europe; Cahyaningsih et al. [36] prioritised MPs in Indonesia based on threat status, Indonesian legislation, native status, part of the plant harvested, and rarity; and Nankaya et al. [39] prioritised MPs in the Maasai Mara region of Kenya based on use value, rarity status, and the part of the plant harvested. However, this had not been previously attempted in Saudi Arabia, so the goal of this paper is to compile and analyse a comprehensive checklist of MPs for Saudi Arabia and then prioritise the most deserving species for active conservation.

Methods

MP Checklist Creation

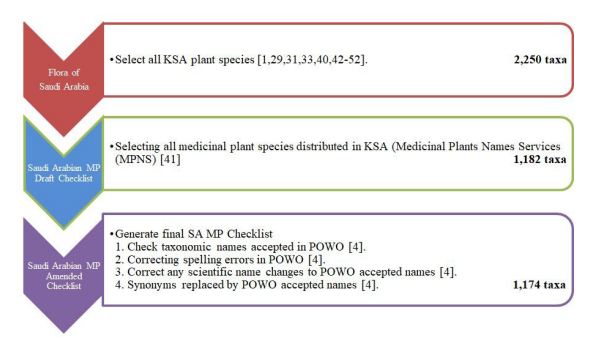

A checklist of MPs in Saudi Arabia was compiled from published works: first Wildflowers of Saudi Arabia [40], only taxa that were used as MPs internationally and recorded in the online Medicinal Plants Names Services (MPNS) were selected due to the possibility of their future use in Saudi Arabia [41]; second MPs studied in Saudi Arabia [1,29,31,33,42-52]. Additionally, to ensure that the taxonomic names used remained legitimate, any misspellings were corrected, and synonyms were included under the scientific name accepted in the online database Plants of the World Online (POWO) [4] (Figure 1).

MP Checklist Prioritisation

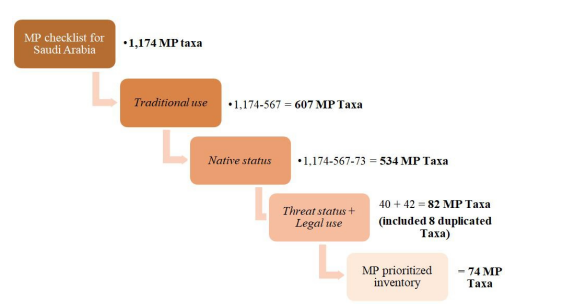

The MP checklist for Saudi Arabia contained 1,174 taxa, but this was considered too large a set of taxa for active conservation, so additional information collected from the literature review was used for prioritised. The prioritisation criteria applied were: traditional use, native status, threat status, and legal use (Figure 2) as follows:

1.Traditional Use: This criterion relies on existing knowledge of MP usage in Saudi Arabia, gathered through comprehensive literature reviews, including sources such as the Handbook of Arabian Medicinal Plants [43]. It has been applied to taxa that are traditionally widely used within the country. Each plant species is identified with details on the parts used (e.g., leaves, roots, bark), the diseases they treat (e.g., cough, fever, rheumatism), and traditional preparation methods (e.g., decoctions, infusions) (Appendix 1).

2.Native Status: The native status of a species has been previously used as a prioritisation criteria for MP by Allen et al. [38] and Cahyaningsih et al. [36]. Plants were classified as native, non-native, or invasive based on botanical records and databases (e.g., Flora of Saudi Arabia and regional herbarium collections). Non-native and potentially invasive species they may compete with or excluded native species [53]; therefore, all non-native alien taxa were excluded from the prioritisation list to prevent competition and displacement of native species.

3.Threat Status: Relative threat status, defined as the relative risk that a species faces of extinction [54], was used as a prioritisation criterion for MP by Cahyaningsih et al. [36], as taxa with higher threat categories are more likely to be threatened with genetic erosion or extinction [55]. Saudi Arabia does not have a complete floral IUCN-based red list using global or regional assessments (https://www.iuc- nredlist.org/). Collenette [40] did provide a subjective threat assessment in her flora based on her own expert assessment but not using IUCN criteria. Given the scarcity of threat assessments available we prioritised any MP taxa that were assessed as threatened using the IUCN categories Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), and Near Threatened (NT); note there are no Critically Endangered (CR) taxa in Saudi Arabia as well as those assessed by Collenette [40] as threatened (Appendix 1).

4.Legal Use: Official sanction collection and use is a MP prioritisation criteria used previously by de Oliveira et al. [56] and is also used here. In Saudi Arabia, the Food and Drug Authority (SFDA) authorises the wild collection and commercial sale / use of a specific subset of MP taxa (listed in Appendix 1) [35]. However, this sanction has resulted in widespread over collection many of these taxa are highly threatened in their natural habitats. Furthermore, there is no monitoring of these taxa. Therefore, this criterion was applied through the information gathered from (SFDA) to protect taxa and ensure their persistence in the wild.

These criteria were then applied to the checklist serially, i.e. first applying the traditional use criterion, then native status and finally, threat status and the legal use criterion. An inventory was then prepared for priority MPs, including the following information: scientific names, authors, vernacular names, plant habits, threat status, plant parts used, uses, and the method of preparation used.

Results

Checklist of MPs in Saudi Arabia

The checklist of Saudi Arabia contains 1,174 MP taxa, consisting of 1,100 species and 74 subspecific taxa within 122 families and 607 genera (Table S1). There are 1,045 native (89.01%) and 129 introduced (10.99%) taxa. The families with the highest number of MP are the Asteraceae and Fabaceae, with 106 species each (9.03%), followed by the Poaceae, which contains 103 species (8.78%), the Amaranthaceae, with 59 species (5.03%), and the Lamiaceae, with 45 species (3.83%). The Brassicaceae and Euphorbiaceae families contain 39 species each (3.32%), followed by the Apocynaceae, which contains 37 species (3.15%). The remaining 114 families contain fewer than 37 species each, constituting less than 3% of the total number of species. Among the genera of MPs, Euphorbia is the genus with the highest number of species (23 species), followed by Cyperus (13) and Solanum, with (12). Cleome, Heliotropium and Vachellia include (11 species each), followed by Amaranthus, Indigofera, Plantago, and Rumex, containing (10 species each). The remaining genera contain fewer than ten species.

Identifying Priority MPs in Saudi Arabia

According to the criteria discussed above, conservation priority was given to 74 MP species in Saudi Arabia (Figure 2), which fall under 35 families and 69 genera (Appendix 1). The plant families most represented are the Fabaceae (10 species/ 13.51%), followed by the Asteraceae and Lamiaceae (8 species each/ 10.81%). Apiaceae include (5 species/ 6.76%). Among the genera of priority MPs, Senna is the dominant genus (3 species/ 4.05%), followed by Dracaena, Salvia and Plantago (2 species each/ 2.70%). Of the 74 priority species, 70 are acknowledged worldwide as MP (MPNS) [41], but the remaining four Lavandula atriplicifolia Benth. (noted in Alqethami et al., 2020), Pyrostria phyllanthoidea (Baill.) Bridson (in Remesh et al. [51]), Vachellia origena (Hunde) Kyal. & Boatwr. (in Abulafatih [42] and Ghazanfar [43]), and Prunus arabica (Olivier) Meikle (in Al-Shanawani [45] and Shabana et al. [52]) are used in Saudi folk medicine (Appendix 1).

According to the chosen criteria, a total of 607 MP taxa are identified as traditionally used in Saudi Arabia, containing 534 native species (Table S2). Based on the IUCN assessments at the global level and Collenette's observations [40], 40 out of the 74 priority MPs are considered threatened. Based on the SFDA list, 42 native species out of 74 are permitted for collection, sale and use. Eight species are threatened and permitted for sale and use by SFDA

(Appendix 1).

For the priority MPs the most frequently used parts of priority MPs are leaves, seeds, or the whole plant (Appendix 1). Most priority medicinal species consist of herbs (39 species/ 52.70%), shrubs (22 species/ 29.73%), and trees (13 species/ 17.57%). Species are prepared for treatment in several ways: as a decoction, infusion, powder, paste, raw, as a drink, oil, dried, drops, through smoke, and by burning or eating. The most observed preparation mode is a decoction, followed by infusion, powder and paste (Appendix 1).

Most MP treat several ailments: Apium graveolens L. (19 ailments); Anethum graveolens L. and Myrtus communis L. (18 ailments each); Lawsonia inermis L. (13 ailments); Matricaria aurea (Loefl.) Sch.Bip., Olea europaea L., and Senegalia senegal (L.) Britton (12 ailments each); Cymbopogon schoenanthus (L.) Spreng. and Origanum syriacum L. (11 ailments each); and Commiphora myrrha (Nees) Engl. (10 ailments). Based on the results, most diseases treated with medicinal plants are digestive system disorders, followed by urinary ailments, dermatological disorders, respiratory system disorders, and cardiovascular disorders.

Discussion

Checklist of Saudi Arabian MPs

Creating a checklist and prioritized inventory of plants is an essential first step in effective conservation [57]. Creating a national checklist of Saudi MP species and adding additional data to allow for priority setting is crucial for conservation. Previously, there were no comprehensive or updated checklist of the MPs of Saudi Arabia. This may be due to a scarcity of qualified taxonomists and conservationists, limited data availability, and significant risks associated with fieldwork in the desert and mountainous regions [48]. Additionally, the information concerning medicinal plants is scattered through numerous sources and is arguably incomplete, so it is necessary to collect and review a wide literature [36], updating and correcting the nomenclature of scientific name, verifying the validity of scientific names through previous studies, and comparing them to relevant websites such as Plants of the World Online (POWO) [4] and the Catalogue of Life (COL) [58]. Moreover, the checklist of MPs should be reviewed by taxonomists so it can be a primary source for future studies and for determining conservation priorities. Here a first iteration of the checklist and prioritized inventory of MPs in Saudi Arabia was presented as a basis for further research into the medicinal properties of plants.

Priority of conservation of MPs in Saudi Arabia

Setting conservation priorities for MPs is essential in conservation planning at national, regional and global levels. This study determined the priority for conservation of native MPs in Saudi Arabia. There are some previous studies that discussed the importance of preserving medicinal plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and recommended developing a plan to prioritise their conservation. Rahman et al. [31] listed 86 species under seven families as the most used in Saudi Arabia, which are: Amaranthaceae, Apocynaceae, Capparaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Lamiaceae, Polygonaceae, and Solanaceae. Seven species of priority MPs in the current study are consistent with their results: Celosia trigyna L., Nerium oleander L., Teucrium capitatum L., Calligonum comosum L'Hér., Mentha longifolia (L.) L., Salvia lanigera Poir., and Thymus decussatus Benth. Yusuf et al[48] listed 61 species under 15 families as the most widely used in Saudi Arabia, which are Boraginaceae, Convolvulaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Fabaceae, Malvaceae, Molluginaceae, Papavaraceae, Portulacaceae, Ranunculaceae, Rhamnaceae, Rutaceae, Tamaricaceae, Urticaceae, Verbenaceae and Vitaceae. Three priority MPs in the current study are also included in their results: Alhagi graecorum Boiss., Clitoria ternatea L., and Senna alexandrina Mill. Regarding the priority families of MPs, this study indicates that Fabaceae is the most represented family, which follows the findings of Yusuf et al. [48].

According to legal use, the SFDA has published a list of 131 MP species that are allowed to be sold in Saudi herbal markets, which includes 42 native plant species (Appendix 1). The priority list of MPs contains 40 threatened species based on IUCN [54] and Collenette [40]. Only three species, Celosia trigyna L., Nerium oleander L., and Thymus decussatus Benth., are consistent with the results of Rahman et al. [31]. This may be due to their reliance on only seven families.

In Saudi Arabia many people still prefer to use wild collected MPs for effective treatment of many diseases. The increasing demand for them has lead to over-collection and a decline in their numbers, threatening them with extinction [59,60]. Other threats include overgrazing, overharvesting, climate change, and urbanisation [60], which also increase the risk of extinction, so there is an urgent need to preserve these species. This study indicates that eight out of 74 species are most vulnerable to extinction due to their popular demand and traded in the markets. They were also assessed as threatened with extinction by Collenette [40], they are Anethum graveolens L., Apium graveolens L., Glebionis coronaria (L.) Cass. ex Spach, Brassica rapa L., Glycyrrhiza glabra L., Thymus decussatus Benth., Lavandula atriplicifolia Benth., and Myrtus communis L.

Most MP species are herbs, followed by shrubs and trees. Similar observations were made by Al-Sodany et al. [47] and Ullah et al. [49]. Leaves are the most frequently used part of MPs, which aligns with results reported in previous studies [49,51,61]. According to Remesh et al. [51], leaves are easy to obtain as they contain many phytochemicals such as alkaloids, tannic acid, glycosides, saponins, essential oils and numerous therapeutically active secondary metabolites [62]. This could explain why leaves are the most used part of the plant in folk medicine. Regarding decoction being the most observed mode of preparation, a similar observation was made by Youssef [33]. This study also revealed that most MPs are used to treat ailments of the digestive system, which corresponds to the results in previous literature [33,62,63]. This may be due to the large number of digestive system problems around the world, which motivated the pursuit of MPs that could treat them [64].

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of MP in Saudi Arabia's healthcare system. From an initial checklist of 1,174 MP taxa, a prioritised inventory of 74 species belonging to 35 families and 69 genera was identified. All these prioritised species are currently used in traditional medicine to treat various diseases. However, it is crucial to study and examine these priority plants under laboratory conditions to identify any potential side effects. This study can significantly contribute to raising public awareness within Saudi Arabia about the importance of MP conservation. It serves as a valuable tool for researchers and conservation scientists by:

- ● Informing conservation strategies: The identified priority inventory can guide the development of suitable conservation techniques, both in natural habitats (in situ) and in controlled environments (ex situ).

- ● Identifying Conservation Gaps: Gap analyses can be conducted using this data to identify areas where additional conservation efforts are most needed, for both in situ and ex situ approaches.

- ● Establishing a Red List: The IUCN Red Listing Criteria can be applied to prioritise species based on their threat level, creating a Red List of vulnerable MPs in Saudi Arabia.

- ● Climate change impact assessment: Climate change modelling can be used to identify taxa requiring active conservation measures and to predict how climate change might affect the overall diversity of medicinal plants in Saudi Arabia.

- ● Evaluating current conservation measures: The study can help assess the effectiveness of existing conservation strategies and suggest improvements where necessary.

- ● Studying the properties of lesser-known Plants: Research can focus on the medicinal properties of lesser-known plants in the priority inventory.

- ● Exploring sustainable harvesting Practices: This study can promote the development and implementation of sustainable harvesting practices to ensure the long-term availability of medicinal plants for future generations.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Al-Baha University for its financial support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by I.J.A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by I.J.A and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

- El-Shabasy A (2016) Survey on medicinal plants in the flora of Jizan Region, Saudi Arabia. Int J Bot Stud, 2: 38-59.

- Qari SH, Alrefaei AF, Filfilan W, Qumsani A (2021) Exploration of the medicinal flora of the aljumum region in Saudi Arabia. Applied Sciences, 11: 7620.

- Gurib-Fakim A (2006) Medicinal plants: traditions of yesterday and drugs of tomorrow. Molecular aspects of Medicine, 27: 1-93.

- POWO (2022) Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: http://www.plantsofthew orldonline.org/ accessed on 20 January 2022.

- Abe R, Ohtani K (2013) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and traditional therapies on Batan Island, the Philippines. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 145: 554-65.

- Addo-Fordjour P, Anning AK, Belford EJD, Akonnor D (2008) Diversity and conservation of medicinal plants in the Bomaa community of the Brong Ahafo region, Ghana. Journal of medicinal plants research, 2: 226-33.

- Schippmann U, Leaman DJ, Cunningham AB (2002) Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues. Biodiversity and the ecosystem approach in agriculture, forestry and fisheries, 1: 1-16.

- Uniyal SK, Singh KN, Jamwal P, Lal B (2006) Traditional use of medicinal plants among the tribal communities of Chhota Bhangal, Western Himalaya. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 2: 1-8.

- Kala CP (2000) Status and conservation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian trans-Himalaya. Biological conservation, 93: 371-9.

- Njoroge GN, Kaibui IM, Njenga PK, Odhiambo PO (2010) Utilisation of priority traditional medicinal plants and local people's knowledge on their conservation status in arid lands of Kenya (Mwingi District). Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 6: 1-8.

- Chen SL, Yu H, Luo HM, Wu Q, Li CF et al. (2016) Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants: problems, progress, and prospects. Chinese medicine, 11: 1-10.

- Chi X, Zhang Z, Xu X, Zhang X, Zhao Z et al. (2017) Threatened medicinal plants in China: Distributions and conservation priorities. Biological Conservation, 210: 89-95.

- Van Wyk AS, Prinsloo G (2018) Medicinal plant harvesting, sustainability and cultivation in South Africa. Biological Conservation, 227: 335-42.

- Brundu G, Peruzzi L, Domina G, Bartolucci F, Galasso G et al. (2017) At the intersection of cultural and natural heritage: Distribution and conservation of the type localities of Italian endemic vascular plants. Biological Conservation, 214: 109-18.

- Dhar U, Rawal RS, Upreti J (2000) Setting priorities for conservation of medicinal plants––a case study in the Indian Himalaya. Biological conservation, 95: 57-65.

- Kaky E, Gilbert F (2016) Using species distribution models to assess the importance of Egypt's protected areas for the conservation of medicinal plants. Journal of Arid Environments, 135: 140-6.

- Martin GJ (1995) Ethnobotany: a methods manual. Chapman and Hall, London.

- Schippmann U (1997) Medicinal plant conservation bibliography, volume 1. Cambridge, UK, IUCN Publications.

- Schippmann U (2001) Medicinal plant conservation bibliography, volume 2. Cambridge, UK, IUCN Publications.

- Van Wyk B, Wink M (2004) Medicinal plants of the World Briza Publications. Pretoria, South Africa, 1: 258

- Bogers RJ, Craker LE, Lange D (2006) Medicinal and aromatic plants: agricultural, commercial, ecological, legal, pharmacological and social aspects. Wageningen, The Netherlands: Springer, 17: 16-21.

- Dauncey EA, Howes M-JR (2020) Plants that cure: A natural history of the world’s most important medicinal 22.plants. Kew Publishing, London.

- Rajasekharan PE, Wani SH (2020) Conservation and utilization of threatened medicinal plants. Springer International Publishing.

- Jha S, Halder M (2023) Medicinal Plants Biodiversity, Biotechnology and Conservation. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity. Springer Nature, Berlin, Germany.

- Bai YH, Zhang SY, Guo Y, Tang Z (2020) Conservation status of Primulaceae, a plant family with high endemism, in China. Biological Conservation, 248: 108675.

- Manish K, Pandit MK (2019) Identifying conserva- tion priorities for plant species in the Himalaya in current and future climates: A case study from Sikkim Himalaya, In- dia. Biological Conservation, 233: 176-84.

- Khan S, Al-Qurainy F, Nadeem M (2012) Biotechno- logical approaches for conservation and improvement of rare and endangered plants of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Journal of Bio- logical Sciences, 19: 1-11.

- Sher H, Alyemeni MN (2011) Pharmaceutically im- portant plants used in traditional system of Arab medicine for the treatment of livestock ailments in the kingdom of Sau- di Arabia. African Journal of Biotechnology, 10: 9153-9.

- Alqethami A, Aldhebiani AY, Teixidor-Toneu I (2020) Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: A gen- der perspective. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 257: 112899.

- Aati H, El-Gamal A, Shaheen H, Kayser O (2019) Tra- ditional use of ethnomedicinal native plants in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine, 15: 1-9.

- Rahman MA, Mossa JS, Al-Said MS, Al-Yahya MA (2004) Medicinal plant diversity in the flora of Saudi Arabia 1: a report on seven plant families. Fitoterapia, 75: 149-61.

- Gaafar ARZ, Al-Qurainy F, Khan S (2014) Assess- ment of genetic diversity in the endangered populations of Breonadia salicina (Rubiaceae) growing in The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using inter-simple sequence repeat markers. BMC genetics, 15: 1-10.

- Youssef RS (2013) Medicinal and non-medicinal uses of some plants found in the middle region of Saudi Arabia. J Med Plants Res, 7: 2501-13.

- Nalawade SM, Tsay HS (2004) In vitro propagation of some important Chinese medicinal plants and their sustain- able usage. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology-Plant, 40: 143-54.

- SFDA (2023) Saudi Food and Drug Authority, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/en/node/66 325 accessed on 25 May 2023

- Cahyaningsih R, Magos Brehm J, Maxted N (2021) Setting the priority medicinal plants for conservation in Indo- nesia. Genetic resources and crop evolution, 68: 2019-50.

- Kala CP, Farooquee NA, Dhar U (2004) Prioritiza- tion of medicinal plants on the basis of available knowledge, existing practices and use value status in Uttaranchal, India. Biodiversity & Conservation, 13: 453-69.

- Allen D, Bilz M, Leaman DJ, Miller RM, Timoshyna A et al. (2014) European red list of medicinal plants. Botanic Gardens Conservation International, UK.

- Nankaya J, Gichuki N, Lukhoba C, Balslev H (2021) Prioritization of Loita Maasai medicinal plants for conserva- tion. Biodiversity and Conservation, 30: 761-80.

- Collenette S (1999) Wildflowers of Saudi Arabia. Na- tional Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Develop- ment (NCWCD). Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- MPNS (2023) Medicinal Plant Names Services Portal, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: https://mpns.science.kew.org/ accessed on 08 March 2023

- Abulafatih HA (1987) Medicinal plants in southwest- ern Saudi Arabia. Economic Botany, 41: 354-60.

- Ghazanfar SA (1994) Handbook of Arabian medici- nal plants. CRC press.

- Ghazanfar SA (2010) Medicinal plants of the Middle East. Genetic resources, chromosome engineering, and crop improvement, 6.

- Al-Shanwani M (1996) Plants used in Saudi folk medicine. Riyadh: King Abdul Aziz City for Science and Technology, 146.

- El-Ghazali GE, Al-Khalifa KS, Saleem GA, Abdallah EM (2010) Traditional medicinal plants indigenous to Al- Rass province, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Medicinal Plants Re- search, 4: 2680-3.

- Al-Sodany YM, Salih AB, Mosallam HA (2013) Medicinal plants in Saudi Arabia: I. Sarrwat mountains at Taif, KSA. AJPS, 6: 134-45.

- Yusuf M, Al-Oqail MM, Al-Sheddr ES, Al-Rehaily AJ, Rahman MA (2014) Diversity of medicinal plants in the flora of Saudi Arabia 3: An inventory of 15 plant families and their conservation management. International Journal of En- vironment, 3: 312-20.

- Ullah R, Alqahtani AS, Noman OM, Alqahtani AM, Ibenmoussa S et al. (2020) A review on ethno-medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 27: 2706-18.

- Dailah HG (2022) The ethnomedicinal evidences per- taining to traditional medicinal herbs used in the treatment of respiratory illnesses and disorders in Saudi Arabia: A re- view. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 29: 103386.

- Remesh M, Al Faify EA, Alfaifi MM, Al Abboud MA, Ismail KS et al. (2023) Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants native to the mountains of Jazan, southwestern Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sci- ences, 10: 218-27.

- Shabana HA, Khafaga T, Al-Hassan H, Alqahtani S (2023) Medicinal plants diversity at King Salman Bin Abdu- laziz Royal Natural Reserve in Saudi Arabia and their conser- vation management. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research, 17: 292-304.

- Hobbs RJ, Huenneke LF (1992) Disturbance, diversi- ty, and invasion: implications for conservation. Conservation biology, 6: 324-37.

- IUCN (2017) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Spe- cies: www.iucnredlist.org accessed on 22 January 2022.

- Tali BA, Khuroo AA, Nawchoo IA, Ganie AH (2019) Prioritizing conservation of medicinal flora in the biodiversity hotspot: an integrated ecological and socioeco- nomic approach. Environmental Conservation, 46: 147-54.

- de Oliveira RL, Lins Neto EM, Araújo EL, Albu- querque UP (2007) Conservation priorities and population structure of woody medicinal plants in an area of caatinga vegetation (Pernambuco State, NE Brazil). Environmental monitoring and assessment, 132: 189-206.

- Magos Brehm J, Maxted N, Ford-Lloyd BV, Martin- s-Louçao MA (2008) National inventories of crop wild rela- tives and wild harvested plants: case-study for Portugal. Ge- netic Resources and Crop Evolution, 55: 779-96.

- COL (2022) Catalogue of Life: https://www.catal ogueoflife.org/ accessed on 20 January 2022.

- Kala CP, Dhyani PP, Sajwan BS, (2006) Developing the medicinal plants sector in northern India: challenges and opportunities. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2: 1-15.

- Ray S, Saini MK (2022) Impending threats to the plants with medicinal value in the Eastern Himalayas Region: An analysis on the alternatives to its non-availability. Phy- tomedicine Plus, 2: 100151.

- Almoshari Y (2022) Medicinal plants used for derma- tological disorders among the people of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A narrative review. Saudi Journal of Biological Sci- ences, 29: 103303.

- Alqethami A, Aldhebiani AY (2021) Medicinal plants used in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: phytochemical screening. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences, 28: 805-12.

- Alqethami A, Hawkins JA, Teixidor-Toneu I (2017) Medicinal plants used by women in Mecca: urban, Muslim and gendered knowledge. Journal of ethnobiology and eth- nomedicine, 13: 1-24.

- Tali BA, Khuroo AA, Ganie AH, Nawchoo IA (2019) Diversity, distribution and traditional uses of medicinal plants in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state of Indian Hi- malayas. Journal of Herbal Medicine, 17: 100280.

- Youssef AMM, El-Swaify ZAS, Al-Saraireh YM, Al-- Dalain SM (2019) Anticancer effect of different extracts of Cynanchum acutum L. seeds on cancer cell lines. Pharmacog- nosy Magazine, 15: 5261-6.

- Hassan-Abdallah A, Merito A, Hassan S, Aboubaker D, Djama M et al. (2013) Medicinal plants and their uses by the people in the Region of Randa, Djibouti. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 148: 701-13.

- Shah A, Rahim S (2017) Ethnomedicinal uses of plants for the treatment of malaria in Soon Valley, Khushab, Pakistan. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 200: 84-106.

- Hayat J, Mustapha A, Abdelmajid M, Mourad B, Ali S et al. (2020) Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants growing in the region of" Oulad Daoud Zkhanine"(Nador Province), in Northeastern Morocco. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 19: 1-12.

- Batanouny KH, Aboutabl E, Shabana M, Soliman F (1999) Wild medicinal plants in Egypt (Vol. 154). The Palm press, Cairo, Egypt.

- Benhouda,A, Benhouda D, Yahia M (2019) In vivo evaluation of anticryptosporidiosis activity of the methanolic extract of the plant Umbilicus rupestris. Biodiversitas Journal of Biological Diversity, 20: 3478-83.

- Bailey C, Danin A (1981) Bedouin plant utilization in Sinai and the Negev. Economic Botany, 35: 145-62.

- Moustafa A, Zaghloul M, Mansour S, Alotaibi M (2019) Conservation Strategy for protecting Crataegus x sinai- ca against climate change and anthropologic activities in South Sinai Mountains, Egypt. Catrina: The International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 18: 1-6.

Tables at a glance

Figures at a glance