Violence Against Women: A Global Public Health Pandemic

Received Date: July 20, 2025 Accepted Date: August 01, 2025 Published Date: August 04, 2025

doi:10.17303/jwhg.2025.12.202

Citation: Rebeca Hidalgo Borrajo, Pilar de Castro-Manglano (2025) Violence Against Women: A Global Public Health Pandemic. J Womens Health Gyn 12: 1-25

Abstract

Violence against women, particularly intimate partner violence and intimate partner homicide, represents a global pandemic affecting 31% of women worldwide with devastating consequences. This multidisciplinary analysis examines violence against women through a public health framework, addressing contextualization challenges and prevalence patterns. Using an ecological model, we analyse individual, relational, community, and social factors contributing to this crisis. Our findings reveal critical deficiencies: fragmented data collection, inconsistent definitions, and inadequate coordination between healthcare and legal systems. We propose formal recognition of violence against women as a "social and health pandemic" requiring urgent action, policies integrating criminal justice, healthcare, and social services.

Highlights

Violence against women affects 31% of women globally, constituting a pandemic

Intimate partner violence and homicide are the most severe manifestations

Critical gaps exist in data collection and mental health responses

Evidence-based interventions like SASA! And IMAGE show 50-76% violence reduction

Formal recognition as a "social and health pandemic" is urgently needed

Keywords: Violence Against Women; Intimate Partner Violence; Public Health; Global Pandemic; Gender-Based Violence; Mental Health; Evidence-Based Interventions; Femicide

Background

The definition of violence against women varies considerably according to variables such as the legal system of each country, fields of action (legal, scientific, political, philosophical paradigms), socio-cultural contexts, psychosocial factors, etc. The Council of the European Union in its document of Council Conclusions on the eradication of violence against women in the European Union (Brussels, March 8, 2010), determined according to "Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union, which states that the Union is founded on the values of respect for human dignity, equality and respect for human rights and that these values are common to the Member States in a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail" (pg. 1.); similarly, it concluded that "violence against women is a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women and negatively affects not only women but society as a whole, and therefore urgent action is required" (pg. 4). The United Nations has defined violence against women as "any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life" (art. 1), the World Health Organization (WHO) accepts this definition and notes that intimate partner violence is the most common form of violence against women. The UN Global Report on Violence against Women (2019) provides an overview of the current situation of violence against women worldwide. The report highlights that violence against women is a violation of human rights and a form of discrimination, and that it affects women and girls of all ages, social classes, education levels and ethnic backgrounds. The report also emphasizes that violence against women is not only a gender-based problem but is rooted in structural inequalities of power and status, which means that combating this phenomenon requires a comprehensive and systemic approach that must be addressed with these inequalities in mind. According to WHO (2021), intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to intimate partner or ex-partner behaviors that cause physical, sexual, or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors. Sexual violence is "any sexual act, attempt to commit a sexual act, or other act directed against a person's sexuality through coercion by another person, regardless of his or her relationship to the victim, in any setting. It includes rape, which is defined as the penetration, by physical or other coercion, of the vagina or anus with the penis, another part of the body or an object, attempted rape, unwanted sexual touching, and other forms of non-contact sexual violence." Violence affects women in all countries unequally, with large differences in prevalence both within and between countries. Recent estimates suggest that between 10% and 53% of women who have ever had a partner have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime [1]. Up to 38% of murders of women are committed by their intimate partner. In addition to intimate partner violence, 6% of women worldwide report having been sexually assaulted by people other than their intimate partner, although data are more limited. Globally, IPV and sexual violence are mostly perpetrated by men against women (WHO (2021), and this constitutes a serious public health problem and a violation of women's human rights.

Based on statistical analyses of data on the prevalence of IPV and sexual violence against women, obtained through population-based surveys based on survivor testimony, in 161 countries and areas between 2000 and 2018, a study conducted in 2018 by WHO on behalf of the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Violence against Women, worldwide, reported that one in three women (30%) have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner or sexual violence by someone other than a partner or both. More than a quarter of women aged 15-49 who have been in a relationship have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence at least once in their lifetime (since the age of 15). Estimates of lifetime prevalence of IPV range from 20% in the WHO Western Pacific Region, 22% in high-income countries and the WHO European Region, and 25% in the WHO Region of the Americas, to 33% in the WHO African Region, 31% in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region, and 33% in the WHO South-East Asia Region (2021). Sociocultural factors shape violent behaviors toward women, including economic factors such as income inequalities; and factors of education, legal provisions and cultural gender practices, exposure to other forms of violence, and racial or class discrimination [2,3]. The highest estimates of prevalence of violence against women are found in settlements [4], indigenous communities [5], conflict zones [6]; and certain regions of the world, such as Asia and the Pacific [7]. Twenty-three countries have been identified as settings with high prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPV. These countries represent the top quintile of prevalence figures for self-reported experiences of physical or sexual violence, records from the past 12 months (Table 1). Classification of high-prevalence countries according to WHO data [8]

Estimates of IPV and non-partner sexual violence, or both, among all women aged 15-49 years by region, from the World Health Organization (Table 2) (WHO), 2018ª provides a picture of the proportions and numbers of women subjected to violence, although this still does not represent the full extent of violence experienced by women, the report notes. Globally, 31% (UI 27-36%) of women aged 15-49 and 30% (UI 26-34%) of women aged 15 and older have been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former husband or intimate male partner, or sexual violence by someone who is not a current or former husband or intimate partner, or to both forms of violence at least once since the age of 15. These estimates are very similar to the 2010 estimates published by WHO in 2013 and are within uncertainty intervals. These findings suggest that, on average, 736 million and up to 852 million women who were 15 years of age or older in 2018 have experienced one or both forms of violence at least once in their lifetime.

As seen in Table 2, the combined prevalence estimates of women aged 15-49 years who have experienced IPV and/or sexual violence by others during their lifetime ranged from 25% (UI 16-38%) in the Western Pacific Region to 36% (UI 32-41%) in the African Region among low- and middle-income countries in each of these WHO regions. In the world's high-income countries, 30% (UI 24-37%) of women aged 15-49 years have experienced IPV or third-party sexual violence (or both) at least once since the age of 15 years, which is similar to the global prevalence. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) presented in November 2019 a report entitled "Violence and Discrimination against Women, Girls and Adolescents: Good Practices and Challenges in Latin America and the Caribbean" that analyzes the serious situation of violence suffered by women in this region. The report points out that the Americas is the most dangerous region in the world for women and that femicide is the most extreme expression of this violence. It also indicates that the lack of effective measures to prevent, investigate and punish femicides perpetuates impunity and encourages their repetition. The report also highlights that most cases of femicide are committed by partners or ex-partners, and that violence against women is aggravated by factors such as racial, ethnic and gender discrimination, poverty, social exclusion and lack of access to justice. The 2021 Sustainable Development Goals Report, pg.36, noted, "The social and economic impact of the COVID19 pandemic negatively affected progress on gender equality: violence against women and girls has intensified; child marriage, which had declined in recent years, is expected to increase; and women have borne a disproportionate share of job losses and increased care work at home. The pandemic has highlighted the need for swift action to address widespread gender inequalities around the world."

The study by authors Vignola-Lévesque, C., & Léveillée, S. (2022), highlights that IPV is a relevant problem worldwide, reporting that 403,201 people were victims of a violent crime in 2017, 30% of whom were abused by an intimate partner [9]. In 2018, in Canada, 99,452 cases of domestic violence were reported to the police [10]. Similarly, they note that, in 2015, Quebec police services recorded 36 attempted murders in the context of an intimate partner, as well as 11 HPIs (intimate partner homicide) [11]. Of these victims, 78% were women. In Canada, 51 intimate partner homicides were committed in 2017, representing 11.6% of all homicides committed across the country [12]. In Spain, 49 intimate partner homicides were committer in 2022 and 20,4% of the partners comitted suicide and 18,5% intended Previous studies report that the most common form of violence experienced by women is IPV [13]. IPV is a global concern [14]. IPV occurs in different settings, across socioeconomic classes, cultures, ages, religious groups [15]. And, in its extreme forms, IPV is a cause of death [16].

Terminology and Definitions

The complexity of violence against women as a phenomenon is reflected in the multiple, often overlapping terms used to describe it. Clear operational definitions are essential for both analytical precision and practical application in public health contexts. Gender-based violence represents the broadest conceptual category, encompassing violence directed against a person based on their gender or violence that disproportionately affects persons of a particular gender. While this term acknowledges that all genders can experience violence, empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that women and girls bear a disproportionate burden. Gender-based violence manifests through physical, sexual, psychological, and economic harm, occurring across both public and private spheres of life. Violence against women, as defined in the UN Declaration of 1993, refers specifically to any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women. This includes threats of such acts, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life. This definition positions violence against women as a specific subset of gender-based violence, acknowledging the particular vulnerabilities and systematic nature of violence targeting women. Intimate partner violence describes behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, sexual, or psychological harm. This encompasses physical aggression ranging from slapping to severe beatings, sexual coercion including forced sexual acts and other forms of sexual abuse, psychological abuse through intimidation, constant belittling and humiliation, and controlling behaviors such as isolation from family and friends, monitoring movements, and restricting access to financial resources or employment. Intimate partner violence can occur between current or former spouses, dating partners, or cohabiting partners, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, though women remain disproportionately affected globally. The term domestic violence carries broader connotations than intimate partner violence, encompassing violence occurring within the domestic sphere between family members. While often used interchangeably with intimate partner violence in common discourse, domestic violence's scope extends to include child abuse, elder abuse, violence between siblings, and violence perpetrated by extended family members within household settings. This broader definition reflects the complex dynamics of violence within family systems. Intimate partner homicide represents the most extreme manifestation of intimate partner violence, involving the killing of a person by a current or former intimate partner. This category includes femicide or feminicide, terms that specifically denote the gender-motivated killing of women, as well as murder-suicides involving intimate partners and honor killings perpetrated by intimate partners. The gendered nature of intimate partner homicide is stark, with women representing the vast majority of victims globally. Structural violence introduces a systemic dimension to our understanding, referring to the ways social structures systematically harm or disadvantage individuals. In the context of violence against women, structural violence manifests through discriminatory laws and policies, economic inequalities that limit women's autonomy and options, institutional barriers to accessing justice and support services, and cultural norms that perpetuate gender inequality. This form of violence often creates the conditions that enable and perpetuate interpersonal violence. Non-partner sexual violence encompasses sexual violence perpetrated by someone other than an intimate partner, including stranger rape, acquaintance rape, sexual assault in conflict settings, and trafficking for sexual exploitation. This category highlights that women's vulnerability to violence extends beyond intimate relationships to broader social contexts. Understanding violence against women requires an intersectional lens that recognizes how multiple identity factors interact to shape experiences of violence. Race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, immigration status, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity, and age all influence both vulnerability to violence and access to support services. This intersectional understanding is crucial for developing inclusive and effective public health responses. These definitions are not mutually exclusive categories but rather overlapping concepts that capture different dimensions of a complex phenomenon. A single act may simultaneously constitute intimate partner violence, sexual violence, and gender-based violence. For instance, forced sex by a husband represents both intimate partner violence and sexual violence, while also reflecting broader patterns of gender-based violence. This conceptual framework allows for nuanced analysis while maintaining clarity about the specific manifestations and contexts of violence against women as a public health pandemic.

Methodology

This study employs a comprehensive analytical approach to examine violence against women through a public health framework, integrating perspectives from multiple disciplines. The methodological design combines systematic document analysis with epidemiological data review to provide a holistic understanding of this global phenomenon. The research process began with a systematic search conducted between January 2010 and March 2023 across major academic databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and SciELO. Additionally, we examined institutional repositories from key international organizations such as the World Health Organization, UN Women, the Council of Europe GREVIO Reports, and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. This dual approach ensured coverage of both peer-reviewed academic literature and authoritative policy documents. Our search strategy employed carefully selected keywords and Boolean combinations. Primary search terms included "violence against women," "gender-based violence," and "intimate partner violence" combined with "public health," "pandemic," or "epidemiology." Secondary searches focused on specific manifestations such as "femicide" or "intimate partner homicide" paired with "prevalence" or "risk factors." To capture the mental health dimension, we also searched for combinations of "mental health" with "perpetrators" or "victims" in the context of intimate partner violence.

Document selection followed rigorous inclusion criteria. We prioritized peer-reviewed articles published between 2010 and 2023, official reports from UN agencies and regional bodies, government statistics and action plans, studies providing quantitative prevalence data, and systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Documents were included if available in English, Spanish, or French to ensure broad geographic representation while maintaining feasibility. We excluded opinion pieces lacking empirical data, studies focusing exclusively on single interventions without broader context, documents without clear methodology, and grey literature without institutional backing. The analytical framework draws on the ecological model established by Krug and colleagues (2003), examining violence against women across four interconnected levels. At the individual level, we analyzed victim and perpetrator characteristics, mental health factors, and personal histories. The relational level encompassed relationship dynamics, power imbalances, and dependency patterns. Community-level analysis focused on social support systems, local norms, and institutional responses. Finally, the societal level examined legal frameworks, gender equality indices, and broader cultural factors. Quality assessment of selected documents considered multiple dimensions including methodological rigor such as sample size and study design, geographic representation to ensure global perspectives, validity of data collection methods including use of standardized instruments, and temporal relevance to current contexts. This multi-faceted evaluation ensured that our analysis rested on robust empirical foundations. The synthesis approach employed narrative integration to identify patterns across different contexts while respecting the complexity of local variations. We compared prevalence data by region, analyzed intervention effectiveness across settings, and examined gaps between policy formulation and implementation. This approach allowed for nuanced understanding while maintaining analytical rigor. We acknowledge several limitations in this analysis. Language restrictions to English, Spanish, and French may have excluded relevant research in other languages. Publication bias potentially favors studies reporting positive intervention outcomes. Variations in how violence is defined across jurisdictions complicate direct comparisons. Additionally, administrative data sources likely underrepresent true prevalence due to systematic underreporting. Despite these limitations, this methodology provides a comprehensive foundation for understanding violence against women as a global public health pandemic.

Analysis

What Issues Does the Contextualization of Violence Against Women Raise?

Violence against women (VAW) can take many forms. It can be acted out through behavior, or it can be psychological and therefore difficult to see or measure. It can be long-lasting and last for long periods, or it can be brief, but intense. It is not a minor problem that only occurs in some sectors of society; rather, it is a global public health problem of pandemic proportions, affecting hundreds of millions of women and requiring urgent action. What is certain is that violence against women is a major global concern, and much attention, resources and sensitivity are required to put in place coordinated strategies to intervene and halt its escalation and worsening. The contextualization of violence against women problematizes any definition of violence and its limits. For example, Walby S and Towers J (2016), carefully specify the concepts of gender and violence. The concept of gender includes both women and men as possible victims of violence so that they can be compared. They include other dimensions of gender: the sex of the perpetrator, the gender-saturated context of the relationship between perpetrator and victim (intimate partner or other family member, acquaintance, or stranger), and whether there is a sexual aspect to the violence. The definition of violence used in this study is connected to the law, involving both action and harm, and addresses repetition by counting all violent events. They report having developed two approaches to the measurement of violence, which correspond to the conceptualization of violence: violence against women and violent crime (or the health consequences of violence); concluding that the differences are not only technical, but are linked to fundamental issues in gender theory and practice; adding that while generic crime surveys have generated much relevant data, the summary statistics produced by official agencies do not put in the public domain the full wealth of data collected by the surveys. These same authors, in their book entitled: "The Concept and Measurement of Violence Against Women and Men" (2017), focus on violence, different forms of violence against women and men. They point out that, these differences in forms potentially have implications for their measurement. The boundary between violence and non-physical coercion is often unclear, so both are included so that they can be measured in relation to each other. In addition, coercion can take nonviolent forms, but it can also include physical force; thus, it straddles the boundary between violence and nonviolence. Specific forms of violence or coercion such as homicide/femicide; assault; sexual violence, including rape; and female genital mutilation (FGM). In addition, they analyze the categories of "domestic violence" and "violence against women". They also ask where to find and collect relevant data, noting that there are two main sources: administrative and survey. Data on violence against women and men are collected during administrative processes by public services, as well as a deliberate effort through social surveys conducted for academic researchers and governments. Determining that, it is a challenge to ensure the use of a common set of definitions and units of measurement that facilitates cooperation among relevant entities and overcomes the current fragmentation and incompatibility among data collectors, without neglecting the requirements of particular services (pg.103). Concluding that, the collection and public reporting of data on violence against women and men is currently fragmented, dispersed across a variety of agencies and methods, using inconsistent definitions and units of measurement. They suggest the implementation of a framework that is consistent and useful for all data users, including services, researchers, and policy makers, which would require applying the framework during the selection processes of data reported to centralized national agencies. However, in some cases, they argue, it would be necessary to change the categories within which data are collected, especially to ensure the use of all three units of measurement (events, victims, and perpetrators) rather than just the one prioritized by the local service (pg.141). Equally problematic is the fact that violence is often defined in terms of physical violence, even to the extent that sexual (physical) violence is sometimes separated from physical violence and not even analyzed as part of physical violence. International studies, including those reported by WHO, argue that domestic violence, gender-based violence and IPV also include and involve non-physical types of violence (such as economic, psychological and emotional types of violence). Violence and violence against women must be understood in a multifactorial way, in relation to social and psychosocial conditions, structures of inequality, government regimes and social movements. It is worth noting that symbolic violence, structural violence (conflict and war zones), and interpersonal violence may not be considered necessary objects of analysis. However, all these contexts can be even more conducive to violence against women. The thematic complexity of violence against women is such that, depending on the topic from which it is approached, the profile of the perpetrator of violence depends. Recent studies investigating psychosocial perspectives of perpetrators of IPV and/or IPH show that there is no single profile of perpetrators of this type of violence. In fact, each subgroup of perpetrators presents specific characteristics [17-21]. In the same direction, the study by Vignola-Lévesque, C., & Léveillée, S. (2022), reveals one more variable to this panorama, the authors report that, few of the typologies identified in the aforementioned studies, include psychological variables associated with emotional management, such as alexithymia. Alexithymia is defined as a personality construct characterized by difficulties in recognizing and distinguishing different emotions and bodily sensations, difficulties in expressing emotions, lack of imagination or fantasy life, and thoughts focused on external rather than internal experience [21-23]. Difficulties in identifying and expressing one's emotions could increase the likelihood of engaging in violent behavior and committing homicide [24,25]. Studies on prevalence of mental illness among perpetrators of intimate partner homicide (IPH), [26-29], report that the prevalence is high in this class of perpetrators. A study by Esther Hava García, 2021, in the prison context, prevalence of mental illness in the Spanish prison setting, concludes that 81.4% of the inmates under study had a dual pathology (substance use disorder together with mental disorder), and in 10.5% of cases, referrals to psychiatric consultation were motivated by the presence of psychotic symptoms; In terms of diagnoses, the most prevalent were personality disorders (68.2%), followed by schizophrenia spectrum disorders (13%). The latter patients (those with schizophrenia) were referred for psychiatric consultation due to the detection of active symptoms of psychosis in 43.6% of cases. Factors such as psychopathy as a predictor of intimate partner violence may vary according to the type of violence, for example, physical versus psychological violence (Robertso EL., et al., 2020) or instrumental versus reactive violence [30]. Regarding the prevalence of psychopathy among intimate partner batterers, according to studies it ranges from 12% to 42% [31-34]. Although the literature on the influence of psychopathy on IPV is extensive, there are conflicting results. Moreover, these results may differ depending on whether analyses are conducted based on total scores, factors or facets. The type of sample analyzed, i.e., whether the sample is from a correctional, community, or clinical setting, also plays a role. Nonetheless, several studies have found psychopathy to be a significant predictor of IPV (Gomez J, et al., 2021) [35-38]. Studies have also revealed that men who kill their partners have significantly higher psychopathy scores and lower levels of empathy, and especially those men who kill their partners have significantly higher psychopathy scores than their female counterparts [39]

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Intimate Partner Homicide (IPH) is a Worldwide Fact

Despite the thematic complexity in determining definitions and collecting data around violence against women, stemming from the variety of reasons given worldwide, evidence support that men represent the majority of perpetrators and women the majority of victims. [40], explore the role of gender in officially reported intimate partner abuse. They note that male offenders continue to make up the majority of offenders with whom the police deal. In this case, males accounted for 87% of offenders, while females accounted for 13% of all offenders. The most common form of violence experienced by women is intimate partner violence (IPV) (World Health Organization (2013). A study by González-Álvarez, JL., et al., 2018, points out that in Spain, homicide perpetrated by a partner or former intimate partner is the leading cause of violent death for women. A global study [41], based on systematic review, conducted in 66 countries found that an intimate partner committed 13.5% of all homicides and 38.6% of female homicides. A national study of female homicides in South Africa (SA) found that, between 1999 and 2009, an intimate partner [42-43] killed approximately 50% of victims. This highlights that IPH is a global public health problem that must be addressed to curb its incidences; understanding the profiles of these accused individuals can help identify potential perpetrators. In Spain, the Government Delegation against Gender Violence (2022) has registered a total of 1,133 female deaths from 2003 to March 2022. Therefore, although Spain is one of the countries with lower rates of IPV against women (IPVAW) and intimate partner homicide against women (IPHAW) [44-45], the rates are still alarming. Intimate partners [46] kill the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports that two-thirds of murder victims in intimate relationships are women, and one-third of female homicide victims. The gender pattern of victimization is more consistent, with women being over-victimized compared to men (Meuleners L, et al., 2008) [47-50]. Globally, evidence suggests that men represent the majority of perpetrators, and women the majority of victims (Melton HC, et al., 2011). Most epidemiological studies analyzing the causes and consequences of IPV have been conducted in the general population [50,51]; however, there is increasing scientific evidence showing an increase in IPV among the young population [52]. A multinational study conducted with a representative sample of 28 European Union countries, shows a current prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPV in women aged 18-29 years of 6.1% (4% among the general population) and a lifetime prevalence of psychological IPV of up to 47.9% (32% in the general population) (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2015) Likewise, older age has been identified as a barrier to leaving a violent relationship [53-54]. It is possible that age interacts with conditions such as immigrant status, social support, economic dependence, functional dependence, etc., and that this intensifies women's vulnerability to IPV in different ways across life stages [55].

Why Is Violence Against Women A Global Public Health Problem?

Violence against women is internationally assumed as a global public health problem with serious consequences, not only for women, but also for their children and society in general; it implies a socio-health phenomenon contributing to high social costs in terms of legal procedures, medical care and social problem solving [56]. Globally, it is estimated that approximately one in three women, after the age of 15, experience physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner during their life course [56]. The reported prevalence of IPV varies between countries and correlates with gender inequalities that, influence and are influenced by norms, legislation, daily life, socio-political contexts, and access to resources, resulting in ostensible disadvantages for women and in greater proportion than for men [57]. Violence against women is a socio-sanitary problem that requires combined and synergic action by health and social services to promote autonomy in its management, mitigate the health consequences (physical and psychological for women and girls), and facilitate therapeutic and social treatment for women victims of violence. For the first time in 1996, violence against women was recognized as a global public health problem when the World Health Assembly adopted a resolution declaring that violence is a major public health problem worldwide. It stressed the urgent need to address violence against women and girls from a gender perspective by analyzing its causes and magnitudes toward the goal of its elimination [58,59]. Two studies by Garcia-Moreno, et al 2015, emphasize the responsibility of governments to develop action plans, including education and other key actions against gender structures that underpin inequality between men and women, to prevent and counter violence against women and girls. Involving governments worldwide results in the fact that this phenomenon of socio-health management is installed as an obligation of governments to generate plans, policies and strategies not only to raise awareness among the general population, through education from an early age; but also to develop measures and strategies to counteract the occurrence and increase of this devastating pandemic that is violence against women; and, similarly, to take appropriate health, social and economic measures in health environments, organizations, communities and provide budgets for their due attention and solution. For example, the legally binding 2011 Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence [60] obliges governments to take all necessary measures. It is a "binding contract" - a legally enforceable agreement. This means that when a government signs a binding convention and does not fulfill its part of the agreement, any of the parties involved can take it to court. In 2017 the CEDAW committee, the United Nations body that oversees the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, affirmed the development of a binding international legal standard on state responsibility [61]. Both CEDAW jurisprudence and the Istanbul Convention address the health sector as an important social actor and emphasize the need for access to health care, adequately resourced services, and trained professionals [62,63].

Discussion

Public Health Approach to Addressing Violence Against Women

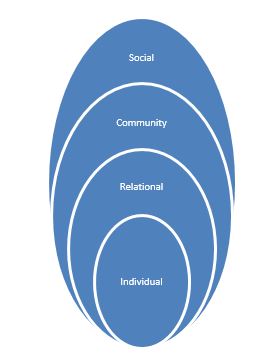

The public health approach to any problem must be interdisciplinary and based on scientific data [64]. It acts in a dynamic and interconnected way with knowledge from many disciplines, including medicine, epidemiology, sociology, psychology, criminology, pedagogy, psychosociology, and economics. This allows the field of public health to be responsive and innovative with respect to a wide variety of scourges, diseases and illnesses throughout the world. Its dynamic activity demands the fulfillment of collective objectives, interconnected in sectors such as health, education, justice, social services, politics, etc., to prevent and solve the problem of violence against women. In this order of ideas, this study shares a vision with the study by [65]. World report on violence and health, in relation to starting aspects not only for violence in general, but for violence against women itself. Violence against women is the result of the interrelated and complex action of individual, relational, community (local) and social factors (ECLAC 2013) (Figure 1). The individual factor describes the characteristics of victims and perpetrators of violence, their gender-related conditions, demographic data, and physical, sexual and mental health descriptors. Psychological characteristics of the perpetrator and victim. Categories of action such as damage (crimes), family and delinquent (criminal) background, and consequences on the physical and psychological health of the woman. The relational factor describes factors of economic and psychological dependence, family ties, partner, friendship, companionship, neighborhood, etc., between the victim and the perpetrator of violence against women. Categories such as violence or coercion, femicide, intimate partner homicide, sexual violence, including rape, female genital mutilation, assault, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, gender-based violence. Risk factors associated with intimate partner and intimate partner homicide (sociodemographic variables, situational variables, and the characteristics of the violence committed) (unemployment and low education of the perpetrator and being older, employed, and having a medium socioeconomic level). The community factor describes social classes, income levels, local measures (legal sanctions, morals), community protection measures, locally perceived gender roles and stereotypes. Risk factors (e.g., legal possession of firearms, previous violence and threats, time after relationship termination), criminogenic environments. Socio-health care. Social organizations. The social factor is related to aspects related to levels of discrimination and structural inequalities between men and women, gender roles, gender stereotypes, legislation, war zones or social conflict, health care, social and health care measures, prevention measures, police control strategies, etc. All these factors necessarily imply a complex interdisciplinary analysis of an anthropological, sociological, psychosocial, economic, epidemiological and psychiatric character. To prevent and eradicate this global scourge, violence against women and girls, governments will have to contribute significant sums in their budgets for attention, prevention and eradication of such violence in all its manifestations. Likewise, it is vitally important to recognize that scientific research is the first link in finding causes and circumstances, and to act accordingly to put into action effective social and health care.

Other Nuances

Not all cases of violence fit the classic gender narrative and need not minimize the value and importance of the gender perspective. Nuanced realities reflect the complexity of the problem, which should be acknowledged rather than invisibilized. “Gender-based violence” can convey attention to the disproportionate impact that sexual and IPV has on women, without implicitly suggesting that only women are negatively affected as its victims. Male and female perpetrators of IPV remain an area in need of further [66]. For example, women frequently present responsibility for the death of their dependent children [67]; just as men are responsible for fatal and nonfatal violence toward their dependent partners, to a lesser degree than men. Rates of female violence appear to increase over time, and their risk of violence is influenced by anger, resentment, hostility, and substance abuse, just like their male counterparts. Both male and female perpetrators of violence report similarly high levels of childhood adversity [68,69] suggesting that early and prolonged exposure to fear may be a risk factor for later violence. Similarly, increased recognition of the role of multiple identities in framing the experience of abuse, awareness of abuse in LGBT relationships. Violence can occur in non-heterosexual couples. It is essential to expand research on the understanding of IPV without exclusions and without reductionist point of views. Professor Julie Goldscheid (2015) has proposed a model that is 'sensitive' to differences in context and use. Replace the default term: violence against women with the default term: gender-based violence or gender-based violence. As it is, the problem links men as victims and sexual and IPV takes many forms. Such "gender-neutral" terms, the author notes, "are most useful when they describe in general terms a category of behavior, rather than a way of describing a particular act. For example, the term 'gender violence' can be used broadly to refer to a variety of behaviors, e.g., sexual and intimate partner violence, in the service of political advocacy, public discourse, and movement building" [70].

Public Mental Health and Violence

Public health involves multidisciplinary and empirical approaches focused on the practice of prevention, treatment, and alleviation of ill health and its impact on populations. Thus, public mental health should focus on research, policies and practices that influence mental health at the population level. In health, social factors, health care inequalities and inclusion policies are determinants. Policies related to violence, and decisions to engage in regional conflicts, can influence the mental health of populations [71]. Economic and social factors have been considered root causes of disease [72], including poor mental health. It is essential to recognize that violence is a public health problem; therefore, the health of women and girls, require actions and solutions. Public health can help increase understanding of the ways in which violence and policies respond to violence, and its unequal social impact on all populations’ strata. It can be argued that the physical experience of victimization is more common in those with low income [73], and poor mental health is directly associated with greater victimization; but even also in those with better resources [74-75]. Unfortunately, mental illness tends to be excluded from political thinking, from government programs, which contributes to mental inequalities and precariousness [76]. The occurrence and impact of violence in society has to do with public policies, including criminal legislation, specifying its scope with data transparency and visibility [77]. Within existing violence data collection practices worldwide, there is strong evidence of correlation between violence and structural characteristics, including income inequality, alcohol consumption rates and population density, which necessarily generates the policy relevance of violence control and prevention.

Precise measures to strengthen the adequate representation of women in power, politics and in all sectors will undoubtedly make violence against women visible and provide transparency and solutions, with direct participation in public bodies and with health approaches to violence [78]. The media should escalate to reports that recognize the importance and seriousness of violence against women, both in reference to victims and perpetrators, which can bring about structural changes. Focusing on identifying and optimally assessing risks to women's health and well-being, including violence in any of its manifestations, leads to transparency and public safety. Gender equity in measuring and responding to violence can have benefits in the process of de-stigmatization of gender role stereotypes, recognition of rights to mental health and public safety in general.

Mental Health of Women Victims of Violence

Gender-based violence, particularly violence against women is a global pandemic (WHO). Violence against women between the ages of 15-44 years causes more morbidity and mortality than malaria, road traffic accidents, and cancer combined [79] The lasting effects of mental health disorders and the nature of violence against women and girls to another attack mean that psychiatric care of patients is of vital importance [80]. The mental health disorders suffered by survivors (post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression) affect their quality of life and the health of their children [81]. For example, a study that analyzed the effects of sexual violence and mental health on wound healing and inflammation found that there were immunological changes in the female reproductive tract in those patients with chronic sexual abuse and depression [82]. Another study describes that, without mental health treatment, long-term patients experienced psychotic episodes, anxiety and depression, with suicide attempts [83]. Unfortunately, the limited rights of women worldwide [84], and the global stigma attached to addressing mental health disorders [85], have led to poor scientific research on this topic. However, scholars have recently noted the need for intervention in this field [86,87] but the results remain contradictory, because of the thematic complexity and because the results may differ depending on the analyses and the basis of total scores, factors or facets (mental disorders). The type of sample analyzed, i.e., whether the sample is from a penitentiary, community or clinical setting, also influences it. A holistic, integrative approach is needed to classify and study the variables that influence violence against women and all its manifestations. Develop medical and community interventions to improve mental health outcomes for women.

Evidence-Based Interventions and Successful Programs

The global response to violence against women has generated numerous evidence-based interventions demonstrating measurable impact across diverse contexts. These programs offer concrete examples of how theoretical understanding can translate into practical solutions, addressing the reviewer's concern about the need for specific, actionable approaches. Community mobilization represents one of the most promising intervention strategies. The SASA! Activist Kit, developed in Uganda, exemplifies this approach through its focus on community-wide transformation of power dynamics. Rather than targeting only victims or perpetrators, SASA! engages entire communities in questioning harmful gender norms and promoting healthy relationships. Rigorous evaluation has demonstrated remarkable results, with communities implementing SASA! showing a 52% reduction in physical intimate partner violence and a 76% reduction in sexual intimate partner violence [88]. The program's success has led to adaptation in over twenty countries across Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, demonstrating both effectiveness and scalability. Similarly, the Stepping Stones program in South Africa illustrates how addressing multiple interconnected issues can reduce violence. Originally designed as a participatory HIV prevention program, Stepping Stones recognizes the intersection between gender-based violence and HIV risk. Through fifty hours of programming delivered over six to eight weeks, the intervention engages young men and women in rural communities in transformative dialogue. Evaluation showed not only a 38% reduction in HSV-2 incidence but also significant decreases in intimate partner violence perpetration among male participants [89], demonstrating the value of integrated approaches. The health sector plays a crucial role in both identifying and responding to violence against women. The Nurse-Family Partnership program, now operating across the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and the Netherlands, provides intensive support to first-time mothers through home visitation. This approach recognizes pregnancy and early motherhood as periods of heightened vulnerability to violence. Through building self-efficacy, connecting women to resources, and early identification of risk factors, the program has achieved a 32% reduction in intimate partner violence among participating mothers [90]. Economic analysis reveals remarkable cost-effectiveness, with $5.70 saved for every dollar invested, making a compelling case for scaling such interventions. In the United Kingdom, the IRIS program (Identification and Referral to Improve Safety) demonstrates how brief training can transform primary care responses to violence. Through just two hours of training for general practice teams, IRIS has achieved a twenty-two-fold increase in identification and referral of intimate partner violence cases [91]. The program's integration into routine healthcare and subsequent adaptation for emergency departments and maternity services illustrates how systemic change can be achieved through targeted capacity building. Economic empowerment emerges as another critical intervention pathway. The IMAGE program (Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity) in South Africa combines microfinance with gender and HIV training, addressing the economic dependence that often traps women in violent relationships. Among over 8,000 participating women in rural South Africa, the program achieved a 55% reduction in past-year physical or sexual intimate partner violence [92,93]. This dramatic impact demonstrates how addressing structural factors like economic dependence can contribute to violence prevention. Mexico's Oportunidades program, later renamed Prospera, provides further evidence for economic approaches. This conditional cash transfer program reached six million households and demonstrated that when women control the transfers, physical violence decreased by 33% [94]. However, the program also revealed that cash alone is insufficient; women's control over resources emerges as the critical factor in achieving protective effects. Legal and justice system interventions have evolved considerably, with the Duluth Model from the United States representing a pioneering coordinated community response [95]. By integrating mandatory arrest policies, prosecution protocols, and batterer intervention programs, Duluth created the first comprehensive criminal justice response to domestic violence. While the model has been adapted in seventeen countries, contemporary iterations increasingly incorporate trauma-informed approaches, reflecting evolving understanding of violence dynamics [96]. Research on protection orders across multiple countries including the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia reveals their potential effectiveness when properly implemented. Studies show 60-80% decreases in violence when protection orders are swiftly issued and consistently enforced [97,98]. However, effectiveness depends critically on having trained police officers and accessible court systems, highlighting the importance of systemic capacity building. Mental health interventions address the psychological consequences of violence for both survivors and perpetrators. Cognitive Trauma Therapy for Battered Women (CTT-BW) provides evidence-based treatment for intimate partner violence-related PTSD. Through ten structured sessions addressing trauma processing, safety planning, and assertiveness training, 87% of participants no longer meet PTSD criteria post-treatment [99]. The manualized nature of this intervention facilitates broader implementation across diverse settings. Perpetrator programs, such as Spain's "Programa Contexto," demonstrate the potential for rehabilitation approaches. This psychoeducational program delivers fifty-two sessions over one year, addressing emotional regulation and challenging traditional masculinity concepts. Evaluation shows recidivism rates of 4.6% among participants compared to 16% in control groups [100], suggesting that therapeutic approaches can complement criminal justice responses. Technology increasingly offers innovative intervention pathways. The myPlan app in the United States provides personalized safety planning for intimate partner violence survivors through secure, private technology. With over 30,000 downloads, the app has demonstrated a 28% increase in safety behaviors among users [101,102]. Similarly, South Africa's Soul City multimedia initiative has reached 82% of the population through television drama, radio, and print materials, successfully shifting social attitudes toward domestic violence over its twenty-year operation [103]. Analysis of successful programs reveals common implementation factors crucial for effectiveness [104,105]. Multi-sectoral coordination ensures that health, justice, and social services work synergistically rather than in isolation. Community engagement facilitates local ownership and cultural adaptation, enhancing both acceptability and sustainability. Sustained funding beyond pilot phases enables programs to achieve population-level impact. Rigorous evaluation through continuous monitoring and outcome measurement ensures accountability and enables program refinement. Survivor-centered approaches that prioritize safety and autonomy maintain ethical standards while maximizing effectiveness. Finally, addressing root causes of gender inequality rather than merely treating symptoms ensures lasting social transformation. These evidence-based interventions demonstrate that violence against women, while pervasive, is preventable through systematic, well-designed programs. The challenge lies not in identifying what works but in generating the political will and resources necessary for widespread implementation. As public health professionals, we must advocate for scaling these proven interventions while continuing to innovate and evaluate new approaches suited to emerging contexts and populations.

Conclusions

This comprehensive analysis confirms that violence against women constitutes a pandemic of devastating proportions, affecting 31% of women globally [106]. The evidence reveals intimate partner violence and intimate partner homicide as the most severe manifestations of this crisis, demanding immediate and sustained public health action. The complexity of this phenomenon, spanning individual, relational, community, and societal dimensions, requires equally sophisticated responses that transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries. Our findings expose critical gaps that continue to undermine effective responses. Data collection systems remain fragmented, with inconsistent definitions and measurement approaches hampering coordination across health, justice, and social sectors [107]. This fragmentation not only impedes accurate assessment of the problem's magnitude but also prevents systematic evaluation of intervention effectiveness. Perhaps most concerning is the persistent neglect of mental health dimensions, both for survivors experiencing trauma and for perpetrators whose untreated psychological issues contribute to violence cycles. Despite robust evidence linking mental health to violence perpetuation and intergenerational transmission, mental health services remain peripheral to most violence prevention strategies [108]. The analysis also reveals a troubling implementation gap. While evidence-based interventions demonstrating significant impact exist, as detailed in our review of programs like SASA! [88], IMAGE [92], and others, these remain isolated success stories rather than systematically implemented solutions. The disconnect between available evidence and actual practice represents a failure of political will rather than knowledge. Based on these findings, we propose five priority recommendations for immediate action. First, governments must formally recognize violence against women as a "social and health pandemic," moving beyond rhetorical acknowledgment to establish mandatory action plans with dedicated budgets, measurable targets, and accountability mechanisms. This recognition should trigger the same urgency and resource mobilization typically reserved for infectious disease outbreaks. Second, the establishment of integrated data systems using standardized definitions and measurements across all relevant sectors is essential. Such systems would enable real-time monitoring of violence patterns, risk factors, and intervention outcomes, providing the evidence base necessary for responsive policy making. Third, mandatory training on violence against women identification and response must be implemented for all health professionals, supported by clear protocols for routine screening, safety assessment, and referral pathways (García-Moreno et al., 2015). The health sector's unique position as a common point of contact for women experiencing violence makes this particularly crucial. Fourth, proven interventions must be scaled from pilot projects to population-level programs. This includes community mobilization approaches like SASA!, economic empowerment programs addressing women's financial dependence, and coordinated community responses integrating criminal justice, health, and social services (Ellsberg et al., 2015). Scaling requires not just replication but thoughtful adaptation to local contexts while maintaining fidelity to core effective components. Fifth, perpetrator mental health must be addressed through accessible treatment programs integrated with criminal justice responses. Current approaches focusing solely on punishment fail to interrupt violence cycles or address underlying factors driving violent behavior [100]. The path forward demands transformation of current fragmented responses into comprehensive, coordinated strategies led by public health principles. This transformation requires moving beyond emergency responses to individual cases toward prevention-oriented approaches addressing root causes. It demands integration rather than parallel systems, with health, justice, education, and social services working from shared frameworks and objectives. It necessitates sustained political commitment reflected in budget allocations, policy priorities, and institutional reforms. The evidence presented in this analysis is unequivocal: violence against women represents a preventable public health crisis of pandemic proportions. We possess the knowledge, tools, and evidence-based interventions necessary to dramatically reduce this violence. What remains absent is the political will to implement solutions at the scale required. Every day of inaction represents lives lost, potential unrealized, and suffering perpetuated across generations. As we approach the 25th anniversary of violence against women being recognized as a public health priority (World Health Assembly, 1996), we must confront an uncomfortable truth: despite decades of advocacy and research, implementation remains woefully inadequate. The question facing governments, institutions, and societies is not whether we can end this pandemic—the evidence clearly indicates we can—but whether we choose to do so. The cost of inaction, measured in human lives and suffering, far exceeds any investment required for comprehensive prevention and response. The time for incremental progress has passed; the magnitude of this crisis demands nothing less than transformative action commensurate with recognizing violence against women as the pandemic it truly is.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor of Law, Elena Iñigo, for her invaluable support and collaboration as a co-supervisor during my doctoral thesis, which forms the basis of this review article. Her guidance, expertise, and continuous encouragement were essential in the development of this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

R.H.B. conceived the study, conducted the literature review, performed the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. P.d.C.-M. provided supervision, contributed to the conceptual framework, and reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

- World Health Organization (2021) Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva: WHO.

- Gibbs A, Dunkle K, Ramsoomar L, Willan S, Shai N, et al. (2020) New learnings on drivers of men's physical and/or sexual violence against their female partners, and women's experiences of this, and the implications for prevention interventions. Glob Health Action. 13: 1739845.

- Montesanti SR (2015) The role of structural and interpersonal violence in the lives of women: a conceptual shift in prevention of gender-based violence. BMC Womens Health. 15: 93.

- Gibbs A, Jewkes R, Willan S, Washington L (2018) Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18-30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: a cross-sectional study and structural equation model. PLoS One. 13: e0204956.

- Valdez-Santiago R, Híjar M, Rojas Martínez R, Avila Burgos L, Rascón Pacheco RA (2013) Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence in women living in eight indigenous regions of Mexico. Soc Sci Med. 82: 51-7.

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Abramsky T, Kone D, et al. (2014) Men's and women's experiences of violence and traumatic events in rural Côte d'Ivoire before, during and after a period of armed conflict. BMJ Open. 4: e003644.

- Jewkes R, Fulu E, Tabassam Naved R, Chirwa E, Dunkle K, et al. (2017) Women's and men's reports of past-year prevalence of intimate partner violence and rape and women's risk factors for intimate partner violence: a multicountry cross-sectional study in Asia and the Pacific. PLoS Med. 14: e1002381.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2020) Data series: 5.2.1 proportion of ever-partnered women and girls subjected to physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former intimate partner in the previous 12 months, by age. SDG Indicators Database. New York: United Nations.

- Beattie S, David JD, Roy J (2018) L'homicide au Canada, 2017. Ottawa: Statistique Canada.

- Conroy S, Burczycka M, Savage L. La violence familiale au Canada: un profil statistique, 2018. Ottawa: Statistiques Canada; 2019.

- Gouvernement du Québec (2017) Statistiques 2015 sur les infractions contre la personne commises dans un contexte conjugal au Québec. Quebec: Gouvernement du Québec.

- Burczycka M, Conroy S, Savage L (2018) Family violence in Canada: a statistical profile, 2017. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- World Health Organization (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: WHO.

- Butchart A, Garcia-Moreno C, Mikton C (2010) Preventing intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Archer J (2006) Cross-cultural differences in physical aggression between partners: a social role analysis. Pers Soc Psychol Rev.10: 133-53.

- Campbell JC, Glass N, Sharps PW, Laughon K, Bloom T (2007) Intimate partner homicide: review and implications of research and policy. Trauma Violence Abuse.8: 246-69.

- Adams D (2007) Why do they kill? Men who murder their intimate partners. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Dutton DG (2007) The complexities of domestic violence. Am Psychol.62: 708-9.

- Elisha E, Idisis Y, Timor U, Addad M (2010) Typology of intimate partner homicide: personal, interpersonal, and environmental characteristics of men who murdered their female intimate partner. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol.54: 494-516.

- Khoshnood A, Fritz MV (2017) Offender characteristics: a study of 23 violent offenders in Sweden. Deviant Behav.38: 141-53.

- Vignola-Lévesque C, Léveillée S (2022) Intimate partner violence and intimate partner homicide: development of a typology based on psychosocial characteristics. J Interpers Violence.37: NP15874-98.

- Sifneos PE (1973) The prevalence of alexithymic characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 22: 255-62.

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD (1999) Disorders of affect regulation: alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hornsveld RH, Kraaimaat FW (2012) Alexithymia in Dutch violent forensic psychiatric outpatients. Psychol Crime Law. 18: 833-46.

- Léveillée S (2001) Étude comparative d'individus limites avec et sans passages à l'acte hétéroagressifs quant aux indices de mentalisation au Rorschach. Rev Que Psychol. 22: 53-64.

- Oram S, Flynn SM, Shaw J, Appleby L, Howard LM (2013) Mental illness and domestic homicide: a population-based descriptive study. Psychiatr Serv. 64: 1006-11.

- Bourget D, Gagné P. Women who kill their mates. Behav Sci Law. 2012;30(5):598-614.

- Sabri B, Campbell JC, Dabby FC (2016) Gender differences in intimate partner homicides among ethnic subgroups of Asians. Violence Against Women. 22: 432-53.

- Robertson EL, Walker TM, Frick PJ (2020) Intimate partner violence perpetration and psychopathy. Eur Psychol. 25: 134-45.

- Blais J, Solodukhin E, Forth AE (2014) A meta-analysis exploring the relationship between psychopathy and instrumental versus reactive violence. Crim Justice Behav. 41: 797-821.

- Huss MT, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J (2014) Identification of the psychopathic batterer: the clinical, legal, and policy implications. Aggress Violent Behav. 5: 403-22.

- Gondolf EW, White RJ (2001) Batterer program participants who repeatedly reassault: psychopathic tendencies and other disorders. J Interpers Violence. 16: 361-80.

- Chase KA, O'Leary KD, Heyman RE (2001) Categorizing partner-violent men within the reactive-proactive typology model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 69: 567-72.

- Fernández-Montalvo J, Echeburúa E (2008) Trastornos de personalidad y psicopatía en hombres condenados por violencia grave contra la pareja. Psicothema. 20: 193-8.

- Kiire S (2017) Psychopathy rather than machiavellianism or narcissism facilitates intimate partner violence via fast life strategy. Pers Individ Dif. 104: 401-6.

- Leistico AM, Salekin RT, DeCoster J, Rogers R (2008) A large-scale meta-analysis relating the Hare measures of psychopathy to antisocial conduct. Law Hum Behav. 32: 28-45.

- Mager KL, Bresin K, Verona E (2014) Gender, psychopathy factors and intimate partner violence. Personal Disord. 5: 257-67.

- Okano M, Langille J, Walsh Z (2016) Psychopathy, alcohol use, and intimate partner violence: evidence from two samples. Law Hum Behav. 40: 517-23.

- Carabellese F, Felthous AR, Mandarelli G, Montalbò D, La Tegola D, et al. (2020) Women and men who committed murder: male/female psychopathic homicides. J Forensic Sci. 65: 1619-26.

- Melton HC, Sillito CL (2012) The role of gender in officially reported intimate partner abuse. J Interpers Violence. 27: 1090-111.

- Stöckl H, Devries K, Rotstein A, Abrahams N, Campbell J, et al. (2013) The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: a systematic review. Lancet. 382: 859-65.

- Abrahams N, Mathews S, Martin LJ, Lombard C, Jewkes R (2013) Intimate partner femicide in South Africa in 1999 and 2009. PLoS Med. 10: e1001412.

- Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Martin LJ, Mathews S, Vetten L, et al. (2009) Mortality of women from intimate partner violence in South Africa: a national epidemiological study. Violence Vict. 24: 546-56.

- Bermúdez MP, Meléndez-Domínguez M (2020) Análisis epidemiológico de la violencia de género en la Unión Europea. An Psicol. 36: 380-5.

- Torrecilla JL, Quijano-Sanchez L, Liberatore F, Lopez-Ossorio JJ, Gonzalez-Alvarez JL (2019) Evolution and study of copycat effect on intimate partner homicides: lessons from Spanish femicides. PLoS One. 14: e0217914.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2013) Global study on homicide 2013: trends, contexts, data. Vienna: UNODC.

- Khalifeh H, Dean K (2010) Gender, and violence against people with severe mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 22: 535-46.

- Kmett JA, Eack SM (2018) Characteristics of sexual abuse among individuals with serious mental illnesses. J Interpers Violence. 33: 2725-44.

- Temiz M, Beştepe E, Yildiz Ö, Küçükgöncü S, Yazici A, et al. (2014) The effect of violence on the diagnoses and the course of illness among female psychiatric inpatients. Arch Neuropsychiatry. 51: 1-10.

- Loxton D, Dolja-Gore X, Anderson AE, Townsend N (2016) Intimate partner violence adversely impacts health over 16 years and across generations: a longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One. 12: e0178138.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH (2006) WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 368: 1260-9.

- Sanz-Barbero B, López Pereira P, Barrio G, Vives-Cases C (2018) Intimate partner violence against young women: prevalence and associated factors in Europe. J Epidemiol Community Health. 72: 611-6.

- Boadu YA, Messing JT, Stith SM, Anderson JR, O'Sullivan CS, et al. (2012) Immigrant and nonimmigrant women: factors that predict leaving an abusive relationship. Violence Against Women. 18: 611-33.

- Sanz-Barbero B, Barón N, Vives-Cases C (2019) Prevalence, associated factors and health impact of intimate partner violence against women in different life stages. PLoS One. 14: e0221049.

- Coker AL, Smith PH, McKeown RE, King MJ (2000) Frequency and correlates of intimate partner violence by type: physical, sexual, and psychological battering. Am J Public Health. 90: 553-9.

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, et al. (2013) The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science. 340: 1527-8.

- Heise LL, Kotsadam A (2015) Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 3: e332-40.

- World Health Assembly (1996) Prevention of violence: a public health priority. Forty-ninth World Health Assembly. Geneva: WHA49.25.

- Burman M, Öhman A (2014) Challenging gender and violence: positions and discourses in Swedish and international contexts. Womens Stud Int Forum. 46: 81-2.

- Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Council of Europe Treaty Series No. 210. Istanbul: Council of Europe; 2011.

- CEDAW General recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19. CEDAW/C/GC/35, paragraph 2. New York: United Nations; 2017.

- CEDAW General recommendation No. 35 on gender-based violence against women, updating general recommendation No. 19. CEDAW/C/GC/35, paragraph 35. New York: United Nations; 2017.

- Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Council of Europe Treaty Series No. 210, Article 20 (2). Istanbul: Council of Europe; 2011.

- Mercy JA, Rosenberg ML, Powell KE, Broome CV, Roper WL (1993) Public health policy for preventing violence. Health Aff (Millwood). 12: 7-29.

- Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, Lozano R (2003) World report on violence and health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Mackay J, Bowen E, Walker K, O'Doherty L (2018) Risk factors for female perpetrators of IPV within criminal justice settings: a systematic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 41: 128-46.

- Friedman SH (2015) Realistic consideration of women and violence is critical. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 43: 273-6.

- Fox BH, Perez N, Cass E, Baglivio MT, Epps N (2015) Trauma changes everything: examining the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offenders. Child Abuse Negl. 46: 163-73.

- Levenson JS, Willis GM, Prescott DS (2015) Adverse childhood experiences in the lives of female sex offenders. Sex Abuse. 27: 258-83.

- Peacock D, Levack A (2004) The men as partners program in South Africa: reaching men to end gender-based violence and promote sexual and reproductive health. Int J Mens Health. 3: 173.

- Siriwardhana C, Ali SS, Roberts B, Stewart R (2014) A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Confl Health. 8: 13.

- Link BG, Phelan J (1995) Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 35: 80-94.

- Brennan IR, Moore SC, Shepherd JP (2010) Risk factors for violent victimization and injury from six years of the British Crime Survey. Int Rev Victimol. 17: 209-29.

- Bhavsar V, Dean K, Hatch S, MacCabe J, Hotopf M (2018) Psychiatric symptoms and risk of victimization: a population-based study from Southeast London. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 28: 168-78.

- Maniglio R (2009) Severe mental illness and criminal victimization: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 119: 180-91.

- Millard C, Wessely S (2014) Parity of esteem between mental and physical health. BMJ. 349: g6821.

- Walby S, Towers J, Francis B (2015) Is violent crime increasing or decreasing? A new methodology to measure repeat attacks making visible the significance of gender and domestic relations. Br J Criminol. 56: 1203-34.

- Heise LL, Raikes A, Watts CH, Zwi AB (1994) Violence against women: a neglected public health issue in less developed countries. Soc Sci Med. 39: 1165-79.

- Strokey E (2015) Scars against humanity: understanding and overcoming violence against women. London: SPCK Publishing.

- Zunner B, Dworkin S, Neylan T, Bukusi E, Oyaro P, et al. (2015) HIV, violence, and women: unmet mental health care needs. J Affect Disord. 174: 619-26.

- PLAN International (2017) Adolescent girls in crisis: voices from South Sudan report. Woking: PLAN International.

- Piroozi B, Alinia C, Safari H, Kazemi-Karyani A, Moradi G, et al. (2020) Effect of female genital mutilation on mental health: a case-control study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 25: 33-6.

- Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Storr J, Nejad SB, Dziekan G, Leotsakos A, et al. (2008) Infection control as a major World Health Organization priority for developing countries. J Hosp Infect. 68: 285-92.

- Arat Z (2015) Feminisms, women's rights, and the UN: would achieving gender equality empower women? Am Polit Sci Rev. 109: 674-89

- Sharps P, Laughon K, Giangrande KS (2007) Intimate partner violence and the childbearing year. Trauma Violence Abuse. 8: 105-16.

- Oram S, Khalifeh H, Howard LM (2017) Violence against women and mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 4: 159-70.

- Aguilar Ruiz R, González Calderón MJ, González García A (2021) Severe versus less severe intimate partner violence: aggressors and victims. Eur J Criminol.

- Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, Nakuti J, Kyegombe N, et al. (2014) Findings from the SASA! Study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med. 12: 122.

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, et al. (2008) Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 337: a506.

- Olds DL, Robinson J, Pettitt L, Luckey DW, Holmberg J, et al. (2004) Effects of home visits by paraprofessionals and by nurses: age 4 follow-up results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 114: 1560-8.

- Feder G, Davies RA, Baird K, Dunne D, Eldridge S, et al. (2011) Identification and Referral to Improve Safety (IRIS) of women experiencing domestic violence with a primary care training and support programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 378: 1788-95.

- Pronyk PM, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Morison LA, Phetla G, et al. (2006) Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 368: 1973-83.

- Kim JC, Watts CH, Hargreaves JR, Ndhlovu LX, Phetla G, et al. (2007) Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women's empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am J Public Health. 97: 1794-802.

- Bobonis GJ, González-Brenes M, Castro R (2013) Public transfers and domestic violence: the roles of private information and spousal control. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 5: 179-205.

- Pence E, Paymar M (1993) Education groups for men who batter: the Duluth model. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

- Shepard MF, Campbell JA (1992) The abusive behavior inventory: a measure of psychological and physical abuse. J Interpers Violence. 7: 291-305.

- Holt VL, Kernic MA, Lumley T, Wolf ME, Rivara FP (2002) Civil protection orders and risk of subsequent police-reported violence. JAMA. 288: 589-94.

- Logan TK, Walker R (2010) Civil protective order effectiveness: justice or just a piece of paper? Violence Vict. 25: 332-48.

- Kubany ES, Hill EE, Owens JA, Iannce-Spencer C, McCaig MA, et al. (2004) Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD (CTT-BW). J Consult Clin Psychol. 72: 3-18.

- Lila M, Gracia E, Catalá-Miñana A (2018) Individualized motivational plans in batterer intervention programs: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 86: 309-20.

- Glass N, Eden KB, Bloom T, Perrin N (2010) Computerized aid improves safety decision process for survivors of intimate partner violence. J Interpers Violence. 25: 1947-64.

- Eden KB, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Messing JT, Bloom TL, et al. (2015) Use of online safety decision aid by abused women: effect on decisional conflict in a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 48: 372-83.

- Usdin S, Scheepers E, Goldstein S, Japhet G (2005) Achieving social change on gender-based violence: a report on the impact evaluation of Soul City's fourth series. Soc Sci Med. 61: 2434-45.

- M Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, et al. (2015) Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. 385: 1555-66.

- Michau L, Horn J, Bank A, Dutt M, Zimmerman C (2015) Prevention of violence against women and girls: lessons from practice. Lancet. 385: 1672-84.

- World Health Organization (2021) Violence against women: key facts. Geneva: WHO.

- Walby S, Towers J (2017) Measuring violence to end violence: mainstreaming gender. J Gend Based Violence. 1: 11-31.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris-Gehring A, Heise L, Amin A, et al. (2015) Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet. 385: 1685-95.

- United Nations General Assembly (2014) Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes, and consequences. A/HRC/26/38. New York: UN.